Ota City, Gunma Prefecture: A Walk in a Deep Town of Chaos: “Brazil City” Reflects “A Little Hope for Japan

Ota City and Oizumi-cho, Gunma Prefecture: A Transformation of a Pleasure Town Once Supported by Subaru and Panasonic One out of Five Foreigners Nowadays, the issue of foreign workers has become an overblown issue.

Many towns have been transformed by the increase in the number of foreigners, redevelopment projects, and policies to clean up entertainment districts. In this series of articles, we will walk through every nook and cranny of this multicultural “deep town” to get a closer look at the realities of this chaotic city.

While the issue of foreign workers has become a prominent issue in recent years, there are some municipalities that are attracting attention as model cases of harmonious coexistence. They are Ota City and Oizumi Town in Gunma Prefecture, the “Brazilian Cities” of Japan. Ota City has about 13,000 foreign residents, while Oizumi Town has about 8,300, or one out of every five residents is a foreigner.

It takes less than two hours by car from Tokyo. After exiting the Ota-Kiryu Interchange on the Kita-Kanto Expressway, a series of huge factories came into view, and after about 10 minutes we arrived at the center of Ota City, where a huge signboard for Subaru appeared.

It was a weekend when I visited, but walking around the Ota Station area, I saw almost no people during the daytime. When I entered a restaurant that was open for business, the owner sighed and grumbled, “This area has been cleaned up a lot.

The area has been cleaned up a lot and the outside appearance has improved, but people don’t come around here on weekends. In the end, it’s a town held together by Subaru and Panasonic.

There was a time when Ota was a prosperous downtown area that was compared to Kabukicho in Shinjuku. On both sides of a 2-km stretch of road from the rotary at the south exit of the station, bars, show pubs, foreigner pubs, and adult entertainment establishments lined the street. However, the atmosphere of the town has drastically changed since the large-scale development in front of the station about 20 years ago and the roundup of illegal adult entertainment establishments.

Even so, the downtown area is still somewhat busy after 9:00 pm. Cars parked on the side of the street appeared, and aggressive touts of cabaret clubs accosted us every few meters we walked. However, compared to the past, the bustle of the nightlife has calmed down. A man who was born here and has worked in the nightlife district for 30 years laments the transformation of Ota.

In the old days, the illegal sex industry called ‘ippatsu-ya,’ where you could play for about 10,000 yen, was in full swing, and the town had everything you needed to drink, hit, and buy. But the redevelopment of the area in front of the station led to a sudden demise of all the sex clubs. After that, the weasel game of opening new stores and then having them busted continued, and now there is only one shop left with Chinese touts. The clientele has also changed considerably. In the past, the main customers were Japanese factory workers and contract workers, but the percentage of these workers has decreased, and now the majority of customers are Japanese in their 50s and 60s living locally. Which economy was better? It was a long time ago.

In the area known as “Ota Minami Ichibangai Shopping Street,” about 20 Filipino pubs still stand side by side. However, according to the owner, there used to be more than 100 pubs in a row. May (pseudonym, in her 20s), who works in a Filipino pub, had a gloomy expression on her face.

The yen has weakened, prices have gone up, and I can’t save enough money to send home to my family. I don’t really see the benefit of working in Japan.

What was striking was the almost complete absence of foreign customers in the downtown area. When asked about the restaurants, most of them said, “No foreigners allowed. We don’t want any trouble.

Migrant Workers “Settling in” Ota

Ota is often mentioned as a city where people live in harmony with foreign nationals, but the awareness of residents varies widely.

While the number of foreign residents has increased to fill the gaping holes in municipal housing complexes that have become noticeably vacant, no major problems were heard of when interviewing people in the city’s urban housing complexes.

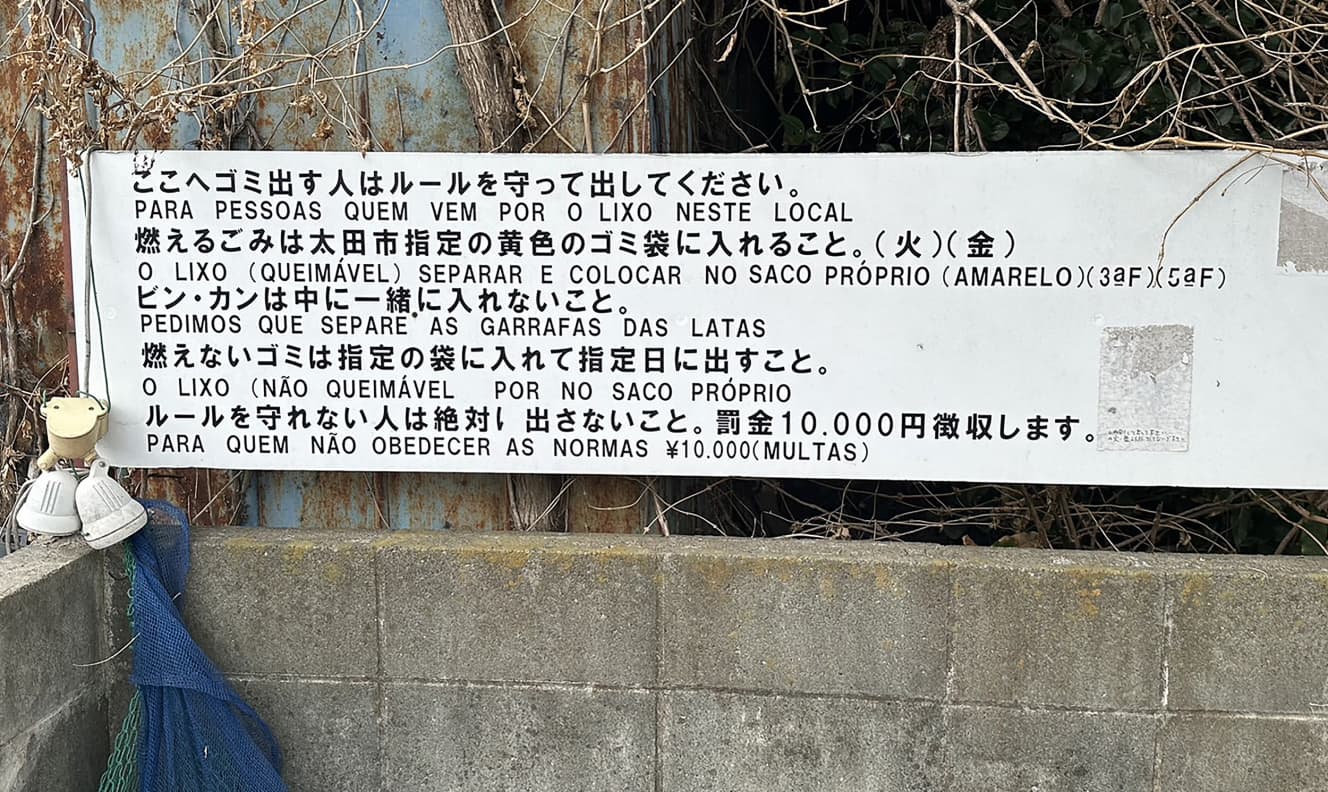

However, there were signs in Portuguese and various other languages at garbage dumps and throughout the complex urging people to be thorough in enforcing the rules. Samy Amad, an Iranian who runs a real estate business in the neighborhood for mainly foreign clients, told us, “The rent in the center of Ota City is very low.

In the center of Ota City, the rent is about 70,000 yen. In the suburbs, the rent is less than 30,000 yen for a one-bedroom apartment and less than 50,000 yen for a three-bedroom apartment, so the number of foreign residents has increased. That is why there are overwhelmingly more complaints in the suburbs. Most of them are from the elderly and are minor complaints about noise and the way garbage is taken out.

A 20-minute drive south of Ota brings one to the center of the neighboring town of Oizumi. The signs and nameplates in the town are all in Portuguese. The town is now known as one of the leading Brazilian cities in Japan, but as of 1986, there were no Brazilians in the town.

However, with the relaxation of immigration laws in 1990 and the shortage of factory workers, the number of Brazilians surged to 1,528 in 1992. Since then, Brasil Town has been formed, and currently there are approximately 4,600 Brazilians living in the town.

Oizumi Town, the largest town in Gunma Prefecture with a population of approximately 41,000, is home to people of over 50 different nationalities. In recent years, the population of Vietnamese and Nepalese has been growing remarkably. In the past 10 years, the number of immigrants from Asia has increased by more than 1,000 people.

The working style of foreigners has changed drastically,” said an official at the town office.

The expression ‘dekasegi’ from South America is no longer appropriate in Oizumi. The number of permanent and permanent residents has increased, and there are third and fourth generation workers. Naturally, they are no longer limited to working in factories, and an increasing number of them are setting up construction and car-related companies or running restaurants and daily necessities stores. On the other hand, many Asian people still come to Japan as technical interns or for special activities. Communities in South America and Asia, and more specifically, in each country, are different.

What Ota and Oizumi have in common is that both the government and private sectors offer a very wide range of services for foreigners. For example, the city office has a multilingual consultation service and a department in charge of foreign residents. In the private sector, there are many staffing agencies for foreigners, which provide job search, medical care, and welfare services in their native languages. An employee of a recruitment agency in Oizumi Town confides, “We are not dependent on foreign workers.

A worker at a recruitment agency in Oizumicho confides, “Without relying on foreign workers, manufacturing will not be possible in Gunma. A cooperative climate has developed among the private sector and local volunteers, and there is an understanding of foreigners.

On the other hand, there were harsh comments from the community about the welfare system. The reality that about one-quarter of the town’s welfare recipients are foreigners led some townspeople to ask bitterly, “Do we really need to support them?

The author spoke to more than 30 foreigners in Ota and Oizumi, and to be honest, the majority of the population did not understand much Japanese. Nevertheless, a Japanese resident in his 30s, who agreed to be interviewed in an area where supermarkets and electronics stores catering to Brazilians are located, offered this suggestion from a completely different perspective.

He said, “Foreigners receive welfare benefits because they don’t fit in well at school or at work. I think one of the reasons is that Japanese people demand too much of them in terms of language skills and behavior. If we demand too much from foreigners, we need to step up to the plate in terms of language and interaction. Not a few of the younger generation in this town are beginning to have this awareness.

On the other hand, how does Oizumi Town appear to foreigners? Thiago Vinicius, a Brazilian who has lived all over the country and now runs a company in Oizumi, says, “When I was a child, I didn’t think of myself as Brazilian,” he says.

When I was a child, I was bullied at school just because I was Brazilian. But times have changed, and although there are challenges, prejudice is decreasing. Rather, young people actively interact with foreigners to understand them, including at local events, volunteer language support, and so on. So it’s a good place to live.”

House of Representatives Representative Hiroyoshi Sasakawa, 57, a locally elected member of the Special Committee on Foreign Workers, has this to say about the state of harmonious coexistence: “The viewpoint that is needed from now on is rather that of the people of Japan.

The viewpoint that is necessary from now on is how to make the community a place where foreign workers can choose to live. There is a limit to what can be done by local communities alone, including education. We are now at a point where the entire country, including ministries and agencies, must think about this issue.

With Japan’s declining birthrate, an increasing number of regions will have to rely on immigrants to survive. The efforts of Ota and Oizumi can be seen as a progressive example of “hope” for Japan, where coexistence will be indispensable. The entertainment district, which once flourished as a workers’ town, has been transformed into a town with a great mission.

Shimei Kurita

Born in 1987. She covers a wide range of topics, including sports, economics, incidents, and overseas affairs. He is the author of “Surviving the COVID-19 crisis: Taxi Industry Survival. Aim for Koshien! The Insatiable Challenge of a Preparatory School Baseball Club” and many other composition books.

From the December 8-15, 2023 issue of FRIDAY

Interview and text by: Shimei Kurita (Nonfiction writer) PHOTO: Takayuki Ogawauchi, Shimei Kurita