Dashi is so tasty that it excites the brain! Dashi” is a surprising scientific evidence that you can get rid of “skinny dieting”.

Dashi” is an ingredient that stimulates the brain along with “oil” and “sugar”–A Scintillating Mechanism

The most common cause of overeating in modern Japan is too much food. Considering the nutritional needs of today’s Japanese people, the key is “how to be satisfied and not overeat. The key to this lies in “dashi.

Research has shown that “dashi,” like fats, oils, and sugars, stimulates the brain’s reward system, making people “addicted” to it. We asked Dr. Toru Fushiki, professor emeritus at Kyoto University and president of Koshien University, about how this mechanism can be applied to the dietary habits of modern people.

The fundamental difference between dashi and low-calorie alternatives is “brain satisfaction.

Dashi, like oil and sugar, stimulates the brain’s reward system and makes us addicted to it. What does that mean?

The “addictive” taste is a feeling of wanting more, of being hooked, and of pleasure. One of the most important elements is that the taste should excite the brain.

The third factor, the presence of something important to you, is what excites the brain, and this is where oil, sugar, and broth come into the picture. Dashi.”

–Why is “dashi” categorized here?

Why is “dashi” classified here? Fats and oils are high in calories and nutrition. Sugar is very important because it is high in calories, maintains blood sugar levels, and is the only nutrition for the brain. The umami of dashi is thought to be a signal to detect the presence of protein.

Foods with a strong dashi umami taste are rich in nutrients. The presence of inosinic acid and amino acids means that protein is present in abundance. In short, what you need is good taste for you.”

Taste is a sense that all animals have. It is a basic sense that is needed to accurately consume the things that are important for life, and it is a very important sense for sustaining life.

–In the experiment with mice, they became “addicted” to bonito broth, while kelp broth did not produce the same results. What is the main type of dashi that stimulates the brain’s reward system?

In the case of humans, Japanese people, bonito, kelp, dried sardines, and shiitake mushrooms all stimulate the brain in the same way.

In the case of mice, eating kelp does not provide protein, and it is not directly connected to the point where the animal wants to eat it because it is essentially necessary, so it showed no interest. Nor are they attached to calorie-free oils or calorie-free artificial sweeteners.

The umami of kelp is the umami of glutamic acid, which the mice probably didn’t find tasty. It just so happens that Japanese people discovered kelp dashi and have been eating it for a long time because they thought it tasted good, but people around the world do not think it tastes good.

The “taste of dashi” is an obsession that occurs when one becomes accustomed to eating it.

–Is the fact that dashi stimulates the brain something that is common only among Japanese people?

No matter where you come from, most foods that you find tasty have the umami of dashi in them. For example, the umami of meat and vegetables. Consomme soup is a mass of umami.

Dashi is eaten all over the world, but the ingredients are not the same. Japanese dashi is made mainly from katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) and kombu (kelp). The taste of dashi becomes an obsession as one becomes accustomed to it, so the type of dashi that stimulates the brain differs from one food culture to another, he says.

Fats, oils, and sugars are important elements that determine the taste of food, but until the Meiji era (1868-1912), the Japanese rarely ate meat or sugar. In a diet devoid of the fats and sugars found in meat, the Japanese discovered that umami is found in dashi, a kind of seasoning made from marine products such as bonito and kelp, as well as mushrooms.

The fact that umami in dashi tastes good through the same mechanism as oil and sugar means that there are two, thereby increasing the number of options from two to three.”

Dashi” stimulates the brain, making Japanese food low in calories and highly satisfying.

–Oil, sugar, and dashi – these three are all stimulating to our brains through the same mechanism, so each of them can be substituted for the other.

If we have to rely on oil and sugar to feel satisfied, we would consume too many calories, leading to obesity and diabetes, but we Japanese don’t mind having umami from dashi there as well. But Japanese people can use the umami of dashi as well. Also, by combining umami with oil, or umami with sugar, we can have a variety of choices that are not high in calories,” he said.

Fats, oils, and sugars, which provide energy for animals, are essential for sustaining life. That’s why they taste good and are addictive. Humans instinctively crave them, so it is difficult to stop consuming them.

If we can substitute Japanese dashi made from bonito flakes or kelp, it satisfies our appetite and makes us feel satisfied, just like oil or sugar, even though it contains very few calories. This is the mechanism by which dashi can be used to lose weight.

For example, soup has a very strong umami taste and is moderately salty, so it is satisfying even without oil or sugar. The umami option in Japanese food makes it possible to create a wide variety of healthy menus.

I feel that the umami of dashi contributes greatly to Japanese food, making it a wonderful meal that is not too calorie-dense, but still very satisfying.

The familiar “taste of peace of mind” tastes good.

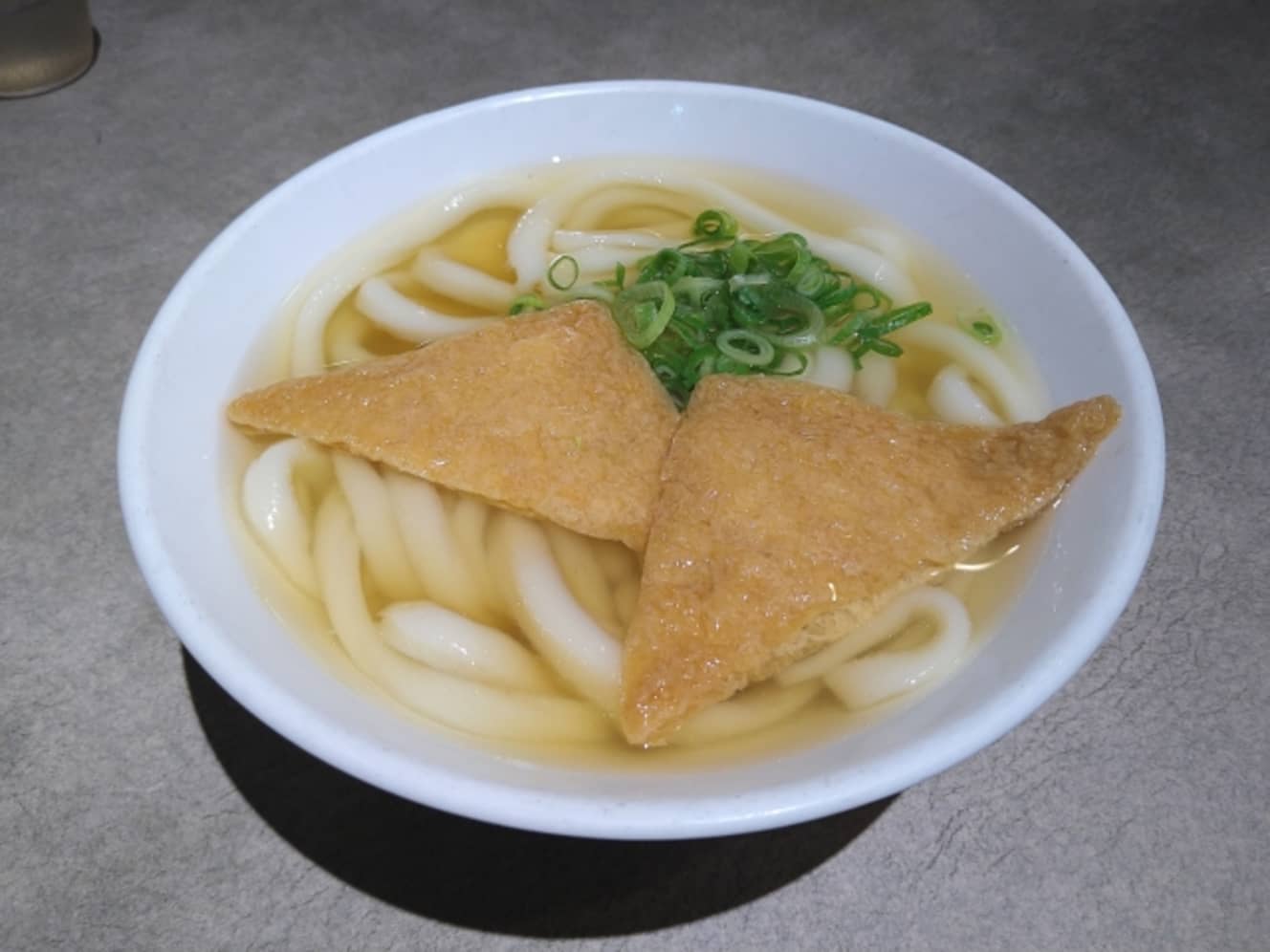

–Cup udon has different flavors of dashi in Kanto, Kansai, and Hokkaido. Do you think that the familiar taste of dashi makes people feel more satisfied?

I think so. For example, I am from Kyoto, so I cannot get used to sweet omelet. On the other hand, people from the Kanto region may feel that the non-sweet omelet from the Kansai region lacks a little bit of sweetness.

But, if the dashi (Japanese soup stock) is effective, don’t you think it tastes good? The dashi is taking the place of the sweetness.

Indeed, many people in the Kanto region also like dashimaki tamago (rolled egg) with plenty of dashi. The umami of the dashi can be felt and the familiar taste can be felt.

The greatness of Japanese dashi lies in the discovery of umami and the synergistic effect of “combined dashi.

Umami was discovered in 1907 by Dr. Kikunae Ikeda of Tokyo Imperial University. He had been interested in kelp dashi since childhood, and succeeded in making dashi from a large amount of kelp, concentrating it, and extracting monosodium glutamate, which he named “umami” in 1908.

Soon after, other Japanese chemists discovered that inosinic acid contained in dried bonito flakes and dried sardines was also an umami ingredient. Dr. Ikeda proposed “umami” as the fifth taste after sweet, salty, bitter, and sour, and today the term “umami” is internationally recognized.

Dr. Kikunae Ikeda discovered that monosodium glutamate extracted from kelp was the basis of umami, but in the early days, it was not easily recognized overseas. No one thought it tasted good when they licked that white powder. However, when it is added to other ingredients, the umami taste is dramatically doubled.

Umami is largely divided into nucleic acids and amino acids. The nucleic acid system is inosinic acid from bonito flakes and guanylic acid from shiitake mushrooms, while the amino acid system is glutamic acid from kelp. Humans are sensitive to umami, and when amino acids and nucleic acids are combined, we perceive a very strong umami taste. It is said that a synergistic effect occurs, resulting in a seven to ten-fold increase in umami taste.

Glutamic acid is found in cheese, tomatoes, and potatoes, and inosinic acid in pork and beef, but the amount is lower than that of kombu, dried bonito flakes, and dried sardines. Considering this, the umami effect of the combined dashi in Japanese cuisine is truly amazing.

The convenience of instant dashi and umami seasonings is more like an inheritance of the taste of Japanese food.

–What do you think about instant dashi and umami seasonings?

AJI-NO-MOTO® was discovered by Dr. Kikunae Ikeda. Monosodium glutamate itself is exactly the same as that found in kelp, so I don’t think there is anything wrong with it. I don’t think there is anything wrong with it. There are people who don’t like chemical seasonings or any other white powdery substance, but I think they are people who don’t like chemistry (bakkegaku).

The name “chemical seasoning” originated in the mid-1960s when it was used in NHK cooking programs to distinguish it from a specific product name. However, the name was changed to “umami seasoning” in 1985 because it was not a name that correctly described the characteristics and manufacturing process.

Kombu is not so abundant anymore. If everyone in Japan used kombu and bonito flakes to make dashi, the resources would be depleted at once. Then Japanese culture would disappear.

I think it is better not to raise the bar for culture. It is fine to make dashi with kombu and bonito flakes and taste it once or twice a year. As long as you understand the taste of dashi, I think instant dashi is fine.

Instant dashi is made from natural bonito flakes and kelp, so it has a natural flavor. I think that by using instant dashi, you are also preserving Japanese food culture.

It is said that Asians have a low insulin secretion capacity and are prone to diabetes and other diseases if they eat a Western-style diet. However, our ancestors found an alternative called “dashi” that suited the Japanese constitution and established a food culture that can be satisfied without oil and sugar.

If it becomes common knowledge in the Japanese diet that oil and sugar can be reduced through the use of dashi, it will greatly help prevent lifestyle-related diseases. Moreover, the scientific evidence that dashi satisfies the brain makes it fundamentally different from a skinny, low-calorie diet.

The taste of dashi becomes addictive as you get used to it. The key to preserving Japan’s food culture and health may be to make good use of instant dashi and become accustomed to the dashi flavor of Japanese food on a regular basis.

Toru Fushiki was born in 1953 in Kyoto Prefecture. Specializes in food and nutritional sciences. After graduating from the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyoto University, he worked at the graduate school of the same university before becoming a professor at the Graduate School of Agricultural Science of the same university in ’94. Professor at Ryukoku University in ’15, Vice President of Koshien University in ’21, and President of Koshien University since ’23. He is a professor emeritus at Kyoto University, director of the Japanese Culinary Academy, NPO, and chairman of the National Council for Japanese Food Culture. Author of “Ningen wa nao de nao de aruku” (Human Eating with Brain) (Chikuma Shinsho), “Koku to umami no hitsu” (Secrets of richness and flavor) (Shinchosha), “Taste and taste science” (Maruzen Publications), “Dashi no shigi” (The mystery of dashi) (Asahi Shinsho), and many other works.

Interview and text by: Kayo Fujioka