‘I want to live in jail…’ The bizarre reality of the indiscriminate killer of the bullet train

In June 2018, prisoner Ichiro Kojima killed and injured three passengers with machetes and knives on board a bullet train. What did the female photographer, Inbe Kawori*, who had been following him, see in Kojima?

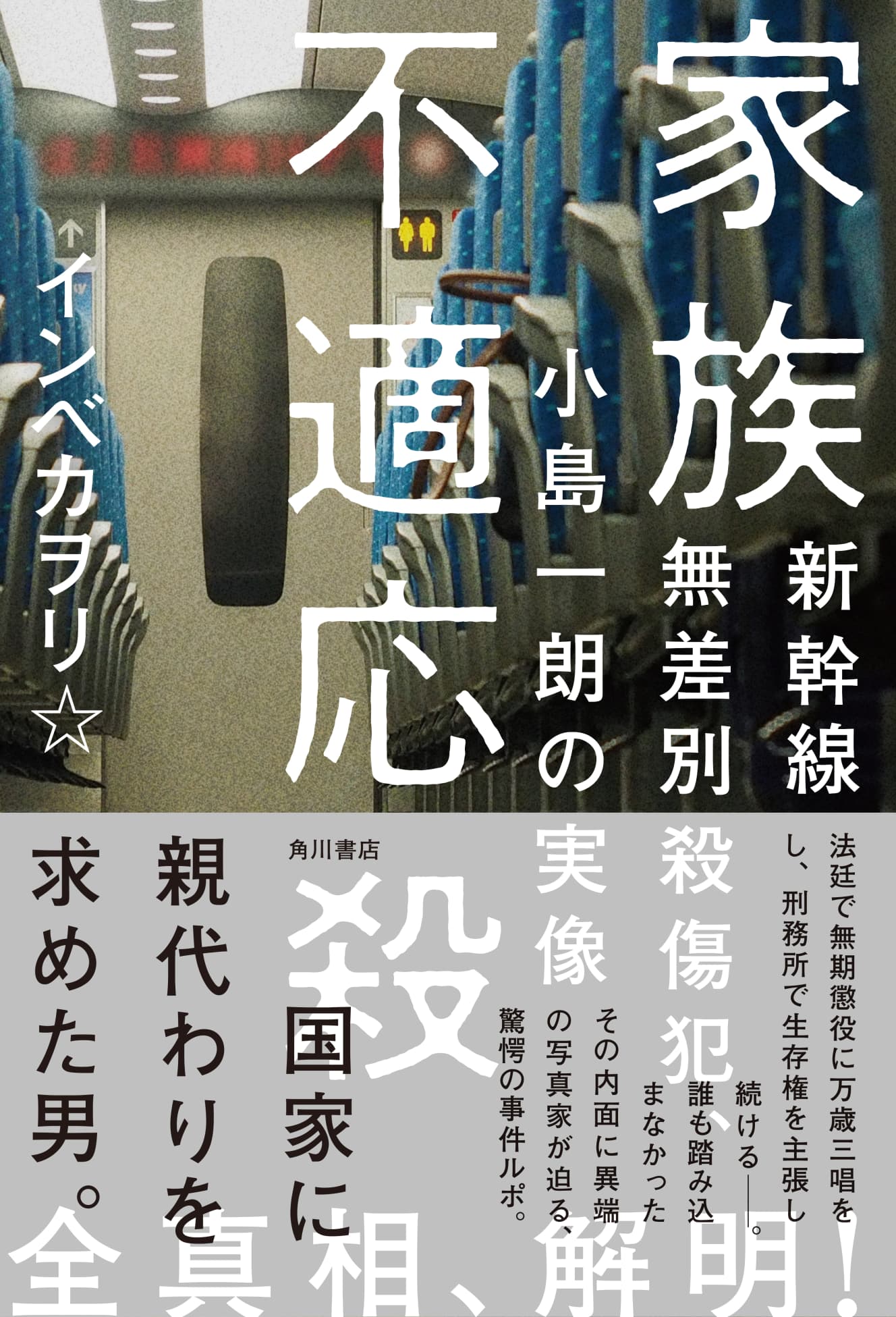

As I boarded the Tokaido Shinkansen from Tokyo Station and took a break, I looked down the aisle and started to see security guards patrolling. This is a crime prevention measure initiated by JR Tokai in response to the indiscriminate killing and wounding incident that occurred on the Tokaido Shinkansen in June 2018.

The incident was committed by Ichiro Kojima, who was 22 years old at the time. On the night of June 9, he slashed the heads and necks of two women sitting next to him with a machete in his hand on the No. 12 car of the Nozomi 265 bound for Shin-Osaka between Shin-Yokohama and Odawara. In December of the following year, the Odawara Branch of the Yokohama District Court sentenced Kojima to life imprisonment (the same sentence sought), and he is now a prisoner.

At the trial, he stated in detail that he wanted to go to prison, and that he wanted to be a “life imprisoned prisoner. He said he decided to commit a crime that would put him in prison for the rest of his life, and that he did so. Perhaps because the outcome was as he had hoped, Kojima sang three cheers in the courtroom after the verdict was handed down.

Mr. Kawori Inbe, a photographer and non-fiction writer, contacted Kojima. In September of this year, he published a book titled ” Kazuro Kojima, a Shinkansen indiscriminate murderer, a true image. In September this year, he published a book titled “The Real Image of Ichiro Kojima, the Shinkansen Indiscriminate Killer.” What is the real image of Kojima as seen by Mr. Inbe? The author, who attended the trial of Kojima at the Odawara Branch of the Yokohama District Court to cover the above article, asked Inbe at a live talk show held at Umeda Lateral on October 5.

What was the real reason for the incident?

Kojima said in his trial that his motive for the incident was his “desire” to live in prison as an indefinite prisoner. But why did he want to live in prison? Through meetings and correspondence with Kojima, Inbe was able to unravel this question and reach a conclusion. He says that his approach to this question was the same as that of a “photographer” approaching a subject.

He said, “If the subject is being interviewed by a lot of reporters, their consciousness will change as they are being interviewed, and it is impossible to get into their mind. However, I wanted to try and find out what I could find out from a person that no one had really done anything about, if I could just drop in and talk to him.

This is because I have been listening to ordinary women as a photographer for about 20 years. I often find that the person I am talking to realizes her true feelings as we talk. I have experienced that there is a “real reason” that is deeper than the “ostensible reason,” and when I delve into it, I feel as if I can suddenly touch the world view that only the person can see. I thought that if I did the same thing with criminals, I might be able to see something.

For three years, I continued to listen to Kojima’s stories, just as I did when I took his photographs. The “real reason” for Kojima’s “incident,” as Inbe put it, was that he had sought a home in the “state” rather than in his “actual family.

It seems that his family relationship was not a good one. Immediately after the incident, his father was interviewed by a weekly magazine and made some inexplicable statements, such as, “I feel like he is my ex-son now,” and “I am no longer related to him. His own mother was an avid volunteer for the homeless, and left all the responsibility of taking care of Kojima to his paternal grandmother. Kojima says that his paternal grandmother harassed him by pointing a kitchen knife at him.

The only family member who showed him any affection was his maternal grandmother who lived in Okazaki City. He grew up at her house until he was three years old. After that, he moved to his father’s side of the family, but his first memory of his grandmother was that she told him, “You are an Okazaki child, go back to Okazaki. Eventually, Kojima was adopted by the “grandmother of Okazaki” and became her child.

Kojima wanted to live in the Okazaki house for a long time, but there were three other houses on the same property where her mother’s brother and his wife lived. His uncle interfered with his work and life, and he had nowhere to go, so he became homeless.

In most families, it’s not very common for an uncle to interfere with his nephew’s work. But my uncle tried to kick him out of the house in Okazaki, contacted my own father to take him in, and did other things.

He tries to starve himself to death, but the police come and kick him out of the Ura-Neigaku. That’s what triggered it, he says.

After deciding to commit murder, Kojima left Uranekake and headed for Suwa Lake by bicycle to build up his physical strength. Using the credit card his grandmother had sent him, he ate at his favorite curry restaurants and drank nourishing sake for three months.

The night before the crime, he bought a machete and a knife to use as the murder weapon, and pretended to use the machete in a park at night. He was named Ichiro after the baseball player Ichiro.

How did he go from “suicidal” to “suicide”?

Of course, Kojima’s actions must have made sense in his mind. However, from the other side, there are some things that don’t seem to add up. One of them is that he initially intended to commit “suicide” by starving to death after a life of homelessness, but in the end he ended up committing “suicide” by seeking a home in the state. Mr. Inbe says, “This is my own opinion,” before continuing.

I think he was obsessed with the idea that he, his son, would starve to death after being homeless because his mother was helping the homeless. If he had died normally, it would have been a suspicious death, but if he had been homeless, his mother would have regretted dying without food, and I imagine that’s what he was aiming for.

Kojima is looking for a family, but if you don’t have one, you can’t have one. If you have a family but you don’t love them enough, you risk your life to try to turn them around.

His homeless life was a conscious effort to support his mother’s focus, and his incidents and jail time were because he wanted the state to play the role of family, not his actual family. …… His thinking is roundabout and not direct. Therefore, “I was frustrated that I couldn’t get to the heart of the matter, and I thought many times that I should stop reporting, that I should give up,” recalls Inbe.

For three years, Mr. Inbe struggled with his reporting, but after his sentence was confirmed and he was sent to prison, which Kojima had originally requested, “it was actually the most difficult time.

He has always been mentally unstable, but in prison he gets violent and goes on hunger strikes. It’s like self-injurious behavior, but he deliberately commits violations and seeks punishment for it. He was put in a protection room, went to a medical prison, and now he is back in prison again.

The contents of my letters were still readable before and after I was sentenced in jail, but after I went to jail, I started to receive incoherent letters that I didn’t know what they were talking about, and when I was almost separated from my actual family for a while, I was asked to take care of my mental health. And when I was almost disconnected from my actual family for a while, I was asked for emotional care. They would ask me to send them a postcard every week or something like that.

After I interviewed Kojima, I got a lot more houseplants in my room. I think that’s where my true feelings came out, or maybe it’s because I wanted to heal.

Mr. Inbe says that he sought solace from the exhaustion of his interviews in the form of houseplants, and his room became covered in greenery, and he still receives letters from him. From this book, it seemed to me that Kojima took action to “let the prison become my family” because “my family was not kind to me. Even after he became a prisoner, he often behaved in a problematic way, and seemed to be happy to be “cared for” by the prison.

He is seeking affection from his adopted maternal grandmother more than his biological mother, and recently he has been seeking affection from his biological father. He gave up and went to prison.

Even though he said that he was going to die, his actual family would not stop him. In prison, if you let an inmate die, it would be a problem, so they try not to let him die. That’s why they let you live, no matter how much you hurt yourself. Even if they refuse to eat, they put a tube through their nose and force them to survive on liquid food. That is what he calls the parent-child relationship, and he says that the home is there as a place where they can survive. So it’s a very inorganic kind of love, but that’s what he wants.

I want to remain a child who can be cared for by my family forever. …… I wonder when he will leave such thoughts behind. When he does, will he realize what he has taken away to be a child?

(Title omitted in the text)

Reporting and writing: Yuki Takahashi

Observer. Freelance writer. She is a freelance writer and has published several books, including "Tsukebi no Mura: Rumor Killed Five People? (Shobunsha), "Runaway Old Man, Crime Theater" (Yosen-sha Shinsho), "Kanae Kijima: The Secret of Dangerous Love" (Tokuma Shoten), "Kanae Kijima Gekijo" (Takarajima-sha), and in the past, "Kasumikko Club: Daughters' Court Hearings" (Shinchosha).