How Railway Timetables Showcase Efforts to Speed Up and Increase Passenger Numbers

A railway timetable refers to a diagram, known as a “train operation chart,” that shows the operation of all trains on a route. The familiar timetables we use are extracts showing only the arrival and departure times of trains at each station. Japan’s railways, renowned for their unparalleled accuracy, are supported behind the scenes by these timetables. Understanding these timetables can deepen one’s knowledge of railways. We asked Takashi Inoue, author of “Railway Timetable Exploration Reading Book,” about the formation of these timetables.

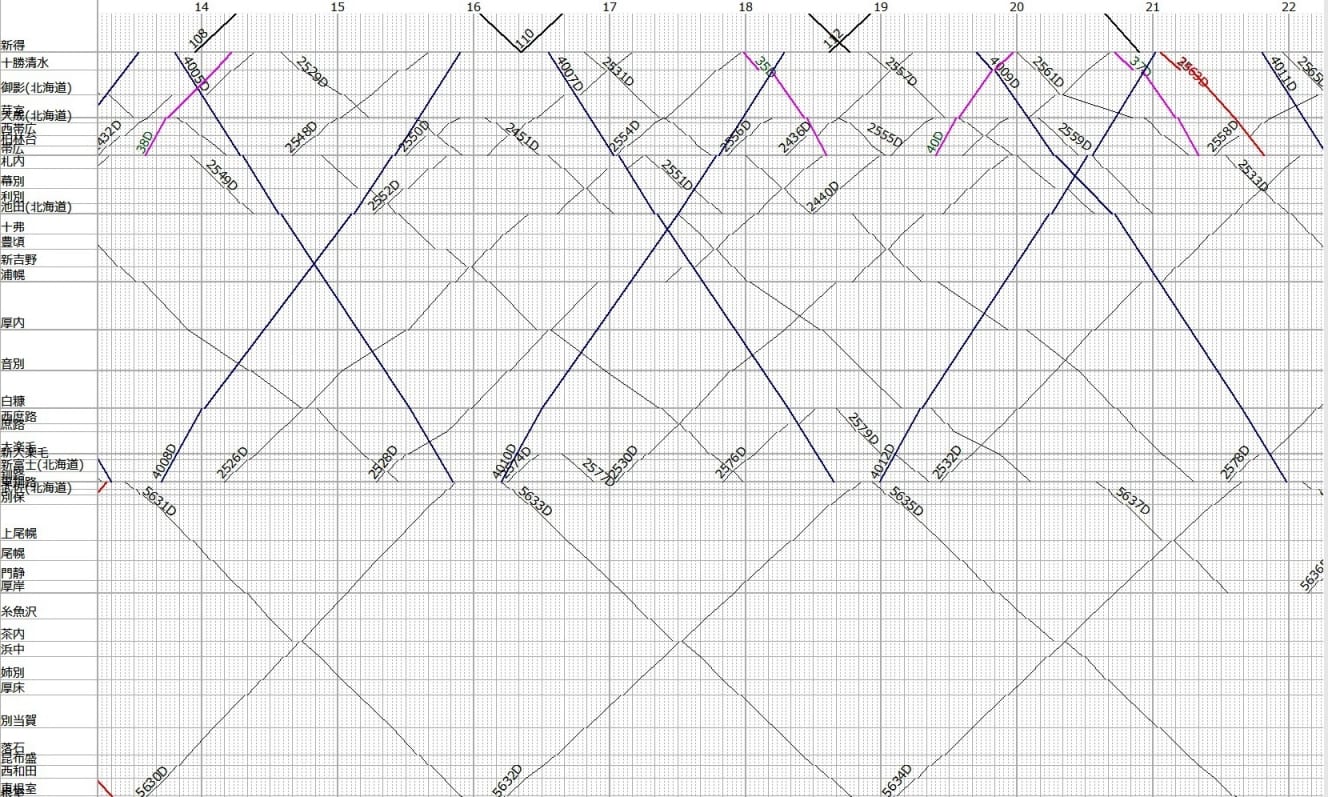

A “train operation chart” is recorded on a horizontally long sheet of paper, with station names on the vertical axis and time markers on the horizontal axis, with lines connecting the arrival, departure, and passing times of each train at each station. The operation of a single train is represented by a single diagonal line, or “schedule.” Although it seems essential for train operations, how does it actually help?

“Since trains are all represented by lines on the operation chart, it’s easy to understand the relationships between individual trains, such as overtakes and encounters, at a glance. It’s difficult to grasp this information from a timetable. While this information may be unnecessary for passengers, it is extremely important for those involved in actual operations.

Each train is assigned a number, and by looking at it, controllers can immediately grasp where the train is currently running and what impact any delays might have.”

Railway timetables are essential for planning operations and managing train schedules. For railway companies, they represent the transportation service, detailing how many trains run to various destinations at different times, and are positioned as a “product” in their own right.

“The timetable reflects the kind of transportation service you want to provide or the service that fits certain circumstances. For example, if there is a demand of 10,000 people daily, but you only have trains with a capacity for 5,000 people, the transportation volume will be insufficient. Naturally, the approach is to operate trains that match the demand.

Another approach is to stimulate demand. For example, in the past, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen only had trains from Tokyo to Hakata in the morning. Now, there are also trains starting from Shinagawa and Shin-Yokohama. For people living west of Tokyo, Shinagawa offers better access than Tokyo Station, and for those near Yokohama, Shin-Yokohama is more advantageous. By setting early morning trains from Shinagawa and Shin-Yokohama, allowing people in those areas to reach Osaka faster, the aim is to stimulate new demand.”

Additionally, there are cases where a flagship train with fewer stops is operated to create a slogan like the fastest express train with the shortest travel time.

“A clear example is the Hokkaido Shinkansen, where some trains have fewer stops to increase speed. For instance, the first Hayabusa train in the morning stops at all stations beyond Ninohe, taking over 4 hours and 20 minutes from Tokyo to Hakodate. However, the No. 7 train stops only at Shin-Aomori after Morioka, cutting the time to under 4 hours, specifically 3 hours and 57 minutes. By operating even one train faster, they can claim a travel time of under 4 hours. This is one way to set up schedules.”

The more passing stations there are, the faster the train arrives, but it can be inconvenient for people using those passing stations. Balancing this is also important. Increasing the number of trains makes things more convenient, but you can’t endlessly add ‘schedules.’ There are practical limitations.

“For example, if you increase a train from a 4-car to an 8-car configuration during rush hour, the transport capacity of one train doubles, but you might not be able to operate a 4-car train, which could impact other services. Since the number of available vehicles and crew is limited, balancing this is crucial.

You might think that adding more vehicles is the solution if there aren’t enough, but each car costs hundreds of millions of yen, making it a significant capital investment. For instance, a 16-car Shinkansen train requires an investment of several billion yen.

Moreover, you need space to store the vehicles and additional expenses for inspections. You must consider whether the investment will be justified by its usage before deciding to increase the number of vehicles. Therefore, it’s common to manage with the existing fleet.”

The shortage of crew is also a serious issue. Recently, for example, Nagano Electric Railway reduced the number of express trains due to a shortage of crew. Additionally, when deciding where faster trains will overtake slower ones, connection issues must be considered. When routes branch off along the way, it adds to the complexity for the planners.

“Especially for JR East’s Shinkansen, there are many constraints, making it like a puzzle. First, the section between Tokyo and Omiya is shared by the Tohoku, Joetsu, and Hokuriku lines. The section between Omiya and Takasaki is also shared by the Joetsu and Hokuriku lines. Additionally, the Yamagata Shinkansen branches off from Fukushima, and the Akita Shinkansen branches off from Morioka. Because these lines also run on conventional lines with single-track sections, the number of possible ‘schedules’ is significantly constrained.

Moreover, the Akita and Yamagata Shinkansen trains run coupled with Tohoku Shinkansen trains, which affects the Tohoku Shinkansen schedule. This further limits the Tohoku Shinkansen’s ‘schedule’ capacity. Additionally, if trains going to Hokkaido need to run as quickly as possible, the constraints become even stricter, and modifying one aspect can cause a ripple effect of impacts. The person in charge of this must have a very challenging job.”

While the difficulties faced by timetable planners are evident, Mr. Inoue notes that creating a timetable to transport more people faster requires the united effort of various departments within the railway company.

“For example, on the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, currently, all Nozomi trains stop at Shin-Yokohama, Shin-Kobe, and Shinagawa. This strategy was implemented to increase the competitiveness of the Shinkansen and attract more passengers. However, the addition of these stops extended the travel time from Tokyo to Osaka, which was originally 2.5 hours.

To address this, improvements were made to the train’s performance, including increasing the maximum speed and the speed at which it can navigate curves. As a result, the travel time has now been restored to 2.5 hours. This achievement was made possible through the cooperation of departments responsible for the vehicles, as well as those supporting power, facilities, and civil engineering.

Additionally, the swift maintenance of trains at Tokyo Station contributes to increased train frequency. The process of unloading passengers, cleaning, and quickly reloading passengers for the return trip is quite challenging. This contributes to high-frequency operations and convenience for passengers.

Therefore, I hope you consider that timetables reflect the overall capabilities of the railway company. While we only see the final timetable and make various comments, there is a lot of work behind the scenes. Although usually only drivers and conductors are visible to passengers, the trains operate smoothly only through the collective effort of everyone involved.”

Railway timetables are often unseen by the public, but interacting with them reveals various aspects of the railway system.

PHOTO: Takashi Inoue