The Unexpected Face of Former Prime Minister Kan and the Merits and Demerits of His Administration

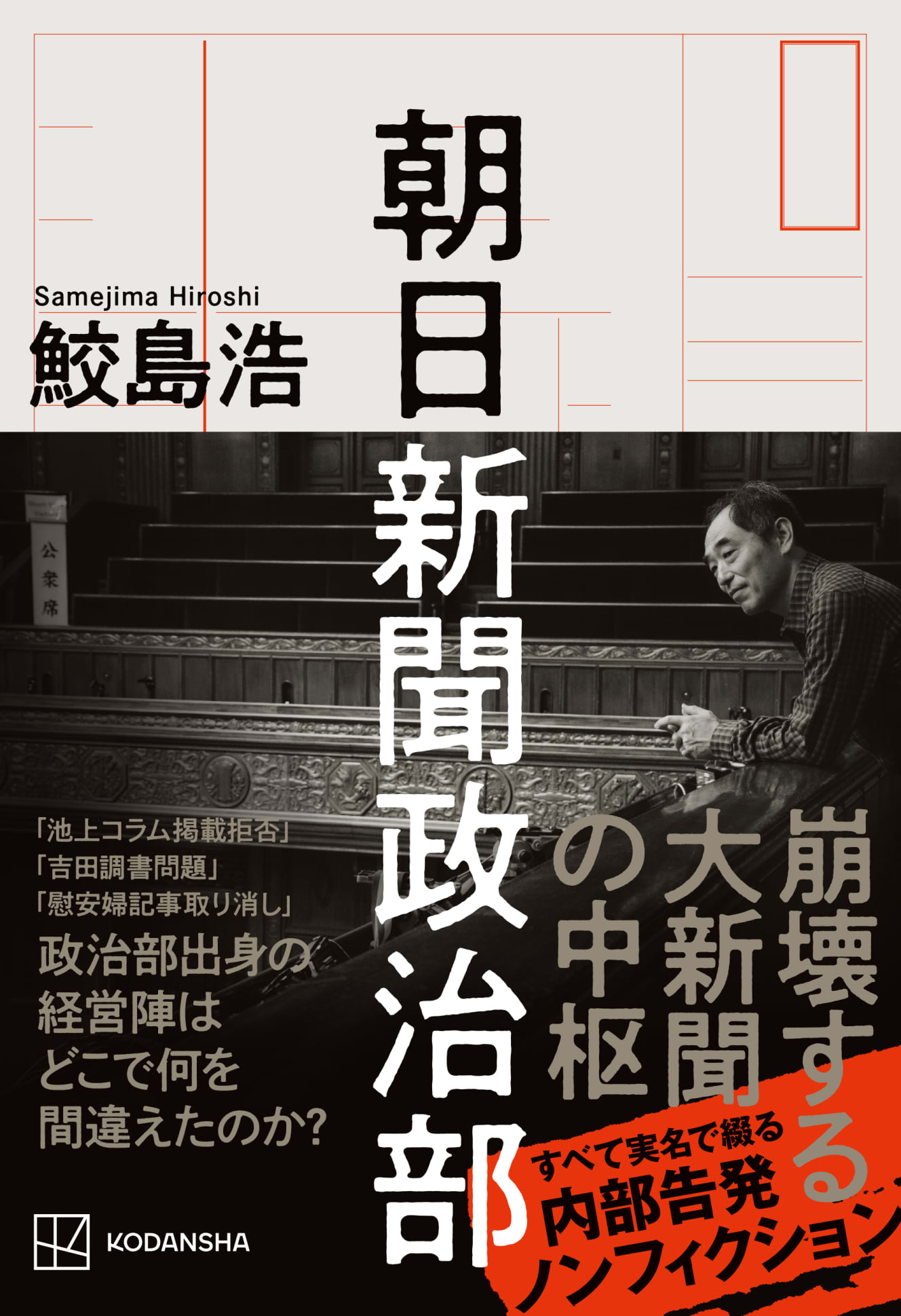

This is the second interview between up-and-coming journalist Hiroshi Samejima, 50, author of “Asahi Shimbun Seiji-bu” (Kodansha ),

and Tokyo Shimbun Social Affairs Department reporter Isoko Mochizuki, 46. In this installment, we take a look behind the scenes of newspaper reporting and the real faces of politicians.

Samejima: Ms. Mochizuki became a household name for her ability to go all in on then Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide at the Kantei Press Club, but not many people know that she was actually famous as a special news reporter in the Shakai (news section).

Mochizuki: No, no, that’s not true. However, I am sure that in a male-dominated organization, female reporters had an advantage over their male counterparts. Since the politicians and government officials were all men, if a reporter of my daughter’s age came to visit me at night, they would say, “Really, you’re doing a great job.”

Of course, there is no denying that sexual harassment is a side effect, but I think that female reporters were able to get more stories in both the police and the Special Investigation Department. However, I wonder if there are female reporters who have a technique like Mr. Samejima’s to offend politicians once by “breaking off the record”.

Samejima: Even Ms. Mochizuki has a technique. It is reputed that she used to get quite a few stories when she was in charge of the prefectural police bureau.

Mochizuki: I heard that the chief of detectives went jogging every morning at 5:00 a.m., so I also went jogging at that time, and I was quite steady. There were times when I jogged every morning, and I would say, “Well, let’s have breakfast together,” and I would bite the hand that feeds me. I think that other companies were wary of me, saying, “Mochizuki has made inroads into the position of chief of detectives. One time, I wrote about a story that Yomiuri Shimbun had prepared as a special report, but I had to copy and paste it. Since I had destroyed Yomiuri’s special story, there were rumors that the chief of the Criminal Investigation Department was the one who leaked the story to Mochizuki. But actually, it was not.

Samejima: The chief of detectives was camouflaging himself (laughs).

Mochizuki: I had a cell phone relationship with the chief of detectives, but he was very tight-lipped. He was always fighting with me, saying, “Why don’t you tell me?” So I felt sorry for him because he treated me like a criminal.

Samejima: As expected. Because you are such a special news reporter, I think you are well aware of the evils of the watchdog system. That is the main reason why you are so critical of the Kantei Press Club.

Difference between getting a story and criticizing power

Mochizuki: In a secret conversation at the Kantei Press Club, I heard the following comment was made. If Mochizuki had been working for Abe or Kan in the Political Affairs Division, she would have been like Akiko Iwata, who worked for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at NHK and produced a series of special stories (laughs).

Samejima: That is not at all understanding the true nature of Ms. Mochizuki, is it? It is precisely because you are not a member of the political press club that’s biting Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide.

Mochizuki: That’s right. Mr. Iwata has won the Newspaper Publishers Association Award and is certainly excellent. However, I can’t help feeling that although he can get a story, his criticism of power is weak. I have my own remorse that I could not express myself critically even when I got a special news item. For example, as Mr. Samejima wrote in “The Asahi Shimbun’s Political Affairs Department,” the investigations by the Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office into Ichiro Ozawa and Yukio Hatoyama of the Democratic Party of Japan on the eve of the change of government were extraordinary even now.

Samejima: From my perspective as a reporter working in the political affairs section, the strangeness of the Special Investigation Department at that time was quite remarkable. With a general election looming that would bring about a change of government, I felt that it was a foolish act that could be described as prosecutorial fashion in terms of democratic governance to conduct a mandatory investigation of the leader of the first opposition party. I thought it was the role of journalism to point out such a crisis of democracy, so I went to the editorial bureau chief’s office by myself, who is ultimately responsible for the paper, and appealed to him that he should write a front-page article saying that democracy is in danger and that Asahi Shimbun should show its resolve.

Mochizuki: That’s right. It is impossible to have such a viewpoint as a watchdog reporter, isn’t it? At that time, journalists outside the existing press club media in Japan, such as Soichiro Tahara and Martin Fackler, were criticizing the prosecutors from the same perspective as Samejima-san. When I reflect on the fact that I was unable to do so, I realize that at the time I was just running with a carrot dangled in front of me. That is where I had tremendous regret.

The existing media only appreciate the importance of lining their pockets, and the basic principle of journalism as the final stab in the back has been lost. I have criticized the Prime Minister’s Press Club, but the evil composition of the club is the same in both the political and social sections.

Samejima: That is why I think that not only the Political Affairs and Social Affairs sections, but even the Economics section should be destroyed. I think the only way to recover is to establish a system of investigative reporting that breaks away from the press clubs. I think the role of the media in the future is to create a system that allows reporters to report independently from the perspective of monitoring power.

Samejima: In the first installment of our dialogue, I explained that politicians hate being called “weak” more than being called “bad”. From your point of view, what kind of politician was Mr. Kan?

Mochizuki: Hearing Mr. Samejima’s explanation made sense to me. I knew that Mr. Kan was a politician who did not want to be called “weak”. That is probably why he strongly opposes my criticism.

Strong pressure on the author

Samejima: Lacking confidence in his language skills, he collects questions in advance and reads out the answers prepared by the bureaucrats. And yet, he answers Mochizuki’s questions in an intimidating manner. On the other hand, he controls the bureaucrats with his personnel power and has the breakthrough power to break through the walls of bedrock regulations.

Mochizuki: This attitude sometimes spins out of control and gives the opposite impression of being “weak”. For example, at the end of last year, a book titled “Who Was Solitary Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide? The author is Takashi Yanagisawa of NTV, a former reporter on Kan’s watch. The book is a candid account of Prime Minister Kan. In a sense, it is a book of revelations, but at the same time, it is a glimpse into Kan’s human side, beautifully expressing his loneliness and anguish. However, when Mr. Kan found out that the book was to be published, he apparently became furious, saying, “Let me see the manuscript,” Mr. Yanagisawa refused to censor the book and it was successfully published.

Samejima: Mr. Kan must have felt betrayed and betrayed by being exposed to his weakness.

Mochizuki: That’s what I think is small. According to this book, Mr. Kan sat down on the sofa and said, “You can write my book.” Mr. Yanagisawa worked for the Metropolitan Police Department and as a correspondent in New York before becoming Kan’s number one. He is not a so-called purely cultured political reporter, but he himself writes that “getting into the news is a means to an end” and that he should be evaluated based on the results of what he has conveyed to the public. It is because of this feeling that he was able to write. It is the true nature of a reporter, but Mr. Kan does not understand this.

Samejima: Perhaps Mr. Kan thought that Mr. Yanagisawa was his protégé. Therefore, his feeling of betrayal must have preceded him. I have always declared to politicians that I would “write” about them, and my style differs from Mr. Yanagisawa’s because I am a political analyst who keeps a close watch on their actions.

Samejima: This is the same situation as when Nobuhisa Sagawa, then Director General of the Finance Bureau of the Ministry of Finance, was promoted to Commissioner of the National Tax Agency after falsifying a sanctioned document to defend Prime Minister Abe’s statement “If my wife and I were involved, I would quit as prime minister and Diet member” in the Moritomo Gakuen national land disposal issue.

Mochizuki: In the first place, I heard that Mr. Nakamura of the police department made the excuse that he did not know whether he could prosecute the case, but a senior prosecutor I know criticized him, saying, “That is not for the police to decide, but for us to decide. The police arrest people because they are strongly suspected of semi-rape, but whether or not they conduct a mandatory investigation makes a huge difference in the evidentiary materials and testimony.”

After all, in an off-the-record meeting with reporters, Nakamura said, “Arresting the head of the press club without knowing the likelihood of prosecuting him could be called suppression of speech. That’s why I didn’t go ahead with the arrest.” “I would have made the same decision if an arrest warrant had been issued for you (press club members),” Nakamura was said to have said. Can any citizen of a country under the rule of law understand this logic? If he really believes this, I would like him to say it out loud and proudly to the public at a press conference, instead of keeping it off the record.

Samejima: So you are saying that only the senior citizens, including political journalists, will be protected. This is the worst kind of logic that leads to distrust of politics.

Mochizuki In the end, Ms. Shiori Ito had no choice but to struggle on her own, and before she knew it, foreign media such as the BBC and the New York Times were increasingly critical of her, calling her “Japan’s dark side” and “a black box”. This is the truth behind “The Japanese Journalism”.

Samejima: It is truly shameful.

*In the “Third Dialogue,” to be delivered on July 6 at 2:00 p.m., we will discuss the ideal form of political reporting from now on.

Hiroshi Samejima was born in 1971. After graduating from Kyoto University’s Faculty of Law, he joined the Asahi Shimbun. After leaving the newspaper in 2009, he launched ” SAMEJIMA TIMES,” which is available for free every day. He also actively provides political commentary videos on YouTube.

Born in 1975 . After graduating from the Faculty of Law at Keio University, he joined the Chunichi Shimbun newspaper in Tokyo. He has worked in the economics and social affairs sections of the newspaper. His sharp questions at the Chief Cabinet Secretary’s press conference became the talk of the town. Author of “Newspaper Reporter” and “Arms Export and Japanese Companies” (both in Kadokawa Shinsho).

Photo by: Shinji Hamasaki