How Image Clubs Started—Without Sexual Services

The world of image play born from fantasy

“Image play” is a genre of sex-industry service in which costumes, props, and image rooms (playrooms decorated to match a specific scenario) are used to enjoy sexual roleplay in various settings such as schools, hospitals, and offices. By recreating male clients’ fantasies and fulfilling their hidden desires, it remains widely popular today.

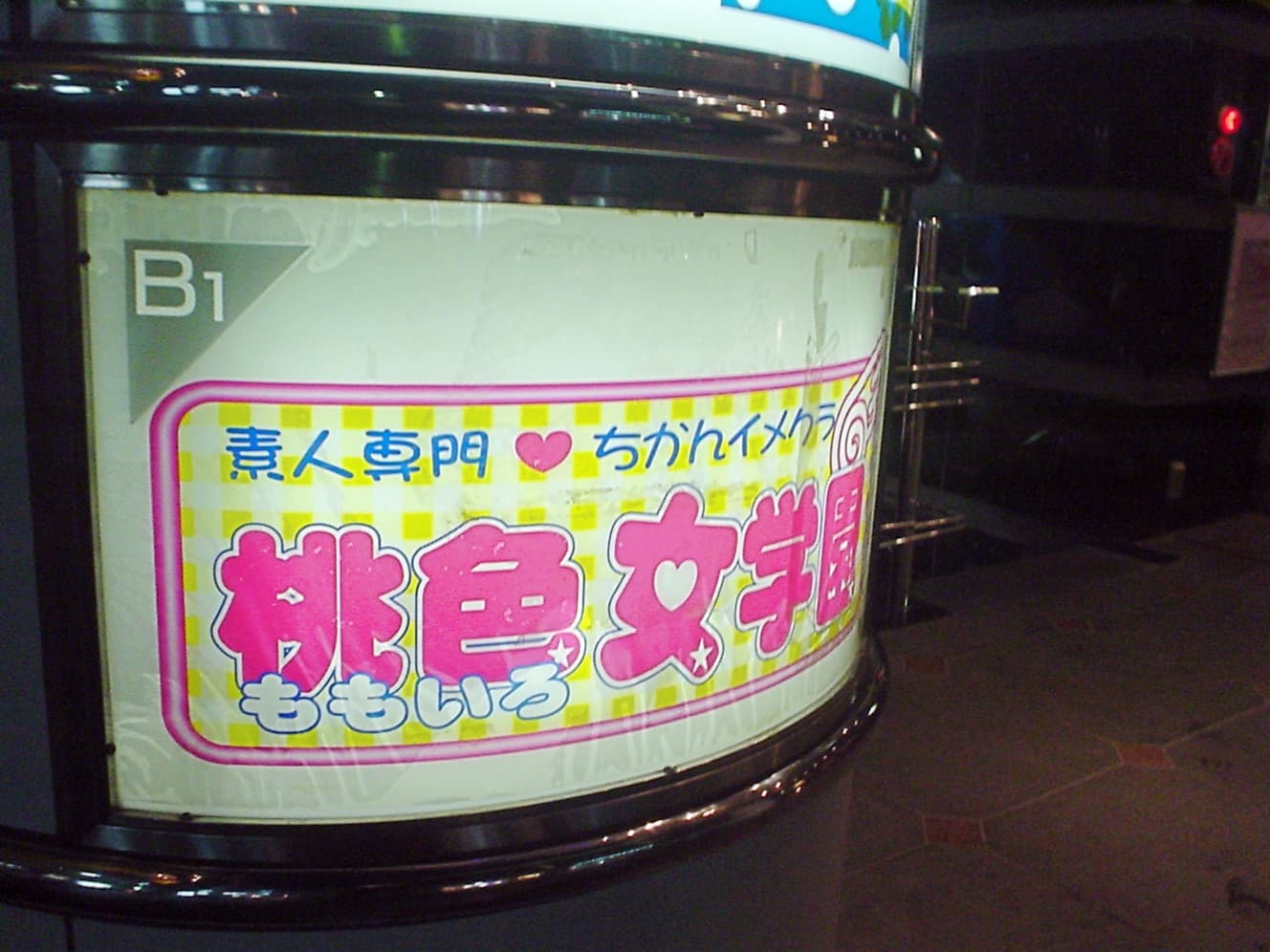

Sex-industry establishments that specialize in image play are generally called “Image Clubs,” or Imekura for short. The official name comes from the Japanese-made English term “Image Club.” Unlike soaplands or fashion health shops, the name Imekura is not legally defined. Any sex-industry business that offers image play can call itself an Ime-kura, regardless of its specific type.

There are diverse business formats, from store-based operations like soaplands, health, and pink salons, to delivery-based services like delivery health and hotel health. They may also be referred to as “Image Club Soap” or “Image Health.”

While Ime-kura are familiar today, their history is relatively short. They began in the late Showa period with small shops run inside apartments.

With the arrival of the Heisei era, shops emerged with elaborately designed playrooms, a wide variety of costumes, or specialized stores dedicated to particular outfits. By the Reiwa era, Ime-kura had spread to every corner of Japan. Even in regional cities that once had only traditional sex-industry establishments, it became possible to enjoy image play with women in cosplay.

Moreover, even non-Ime-kura establishments often use cosplay during events. Pink salons, in particular, frequently hold monthly events featuring unique costumes, making cosplay an essential service often accompanied by discounts.

The trend of image play has even reached underground sex districts. In Osaka’s Tobita Shinchi and Matsushima Shinchi, where women can be seen from the street, wearing costumes has become an established method of attracting customers.

As time passed, costumes became increasingly specialized, with niche outfit shops appearing nationwide offering “Catwoman,” hakama, or “Ryukyuan traditional clothing,” among others. Student-uniform-style idol groups are popular, driving a corresponding trend in uniform cosplay within the sex industry.

This series aims to guide readers through the history of image play in the sex industry and the evolution of Ime-kura as a mirror of Japanese society, from a cultural perspective. It will chronologically explore their unique origins, the evolution and development driven by remarkable imagination, and changes in business formats due to regulation.

OL cosplay pink salons. Office-play has always maintained strong popularity (Kyoto, 2002)

OL cosplay pink salons. Office-play has always maintained strong popularity (Kyoto, 2002)Cosplay started with pink salons

Image play in Japan already appeared in Meiji-era pleasure districts. In 1885 (Meiji 18), Shizuoka City’s Ni-chome red-light district had a place called Horairo that featured a “Western-dress parlor,” where prostitutes dressed in Western-style clothing were employed. They were given stage names like “Hubble,” “Crystal,” “Pink,” “East,” and “Spring,” though they apparently did not gain much popularity.

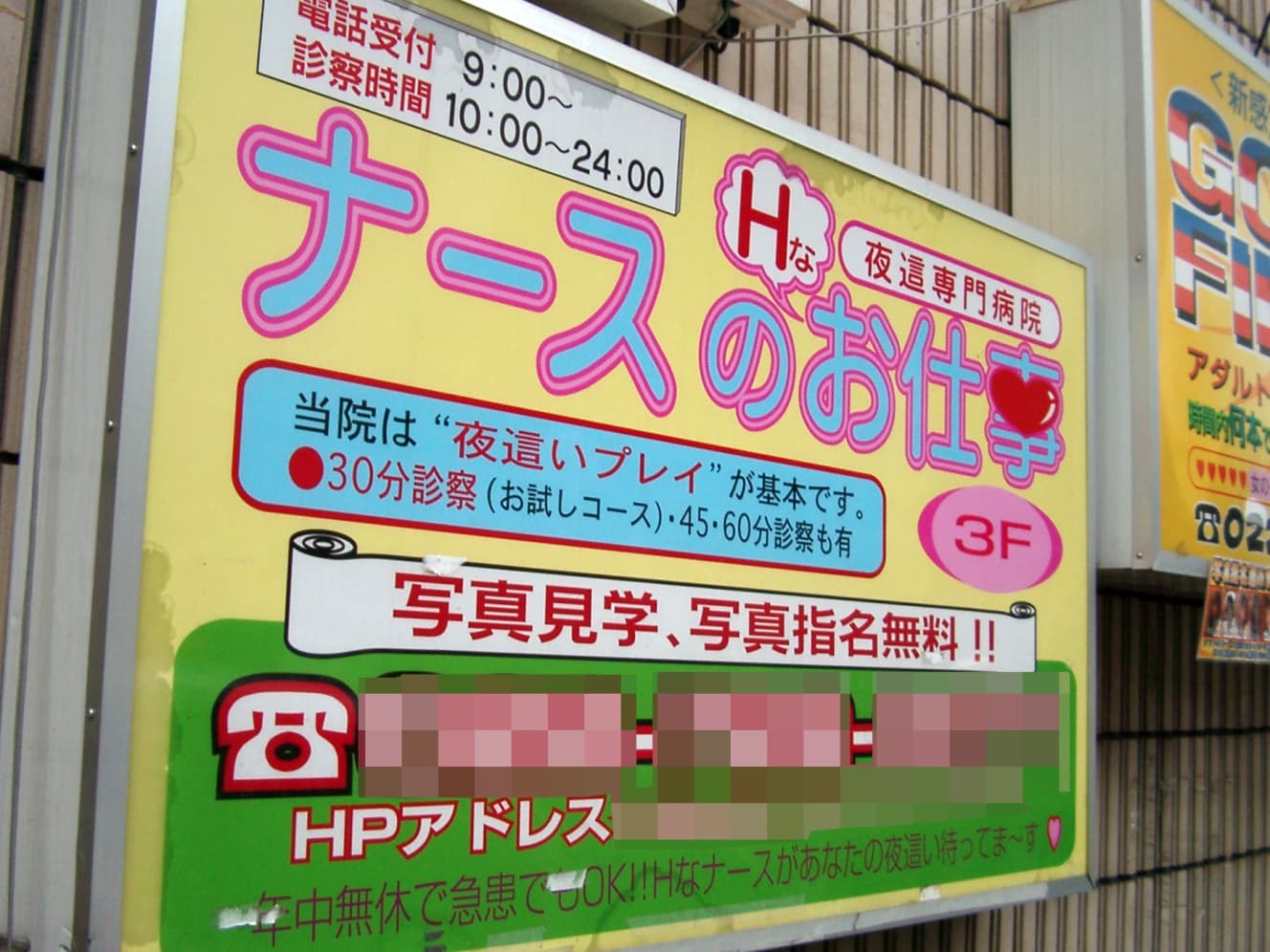

Additionally, during the Russo-Japanese War, when over 2,000 female nurses served in the military for the first time, prostitute cosplay as nurses became popular nationwide.

The prototypes of costume play in postwar Japanese sex work can be traced to pink salons, Turkish baths (today’s soaplands), and SM-oriented establishments. It is said that cosplay started with pink salons. One well-known example after the full enforcement of the Anti-Prostitution Law in 1958 (Showa 33) was the Tokyo “Negligee Salon,” where hostesses wore negligees.

Cosplay was introduced to Turkish baths in 1971 (Showa 46). The following year, anticipating the Winter Olympics, Sapporo’s Susukino district, then riding a tourism boom, creatively began uniform Turkish services—featuring flight attendants, nurses, and schoolgirls—pioneering this nationwide.

In 1976 (Showa 51), two ultra-luxury Turkish baths opened in Kawasaki’s Horinouchi district: the Chinese-style Kinpeibai and Persian-style Arabian Night. These establishments mainly catered to official and private entertainment and flourished. Both now operate as soaplands.

In Tokyo’s Yoshiwara, realistic nun Turkish-bath girls with shaved heads appeared. Previously, Turkish baths modeled after nunneries existed across Japan, but women simply wore white head coverings and robes to act the part. In 1982 (Showa 57), however, a nun at Ama Goten had her head fully shaved, making headlines in weekly magazines and newspapers, and reservations surged.

There was even an image club that mixed nurse cosplay with night-visit play (Sendai, 2002)

There was even an image club that mixed nurse cosplay with night-visit play (Sendai, 2002)Literary works as inspiration

The first image club in Japan opened in 1986 (Showa 61) in a room of an apartment near Uguisudani Station on the JR Yamanote Line in Tokyo. The store, called Yume, had the concept of “Sleeping Beauty.” Customers would watch a woman in pajamas wearing an eye mask, then undress her to view her naked body while pleasuring themselves—an extremely soft form of night-visit play.

Direct contact with the woman was prohibited; breaking this rule would trigger a bell button by the bedside to notify the reception. Women never removed their eye masks until the play ended.

All the women were amateur part-timers, and word of mouth gradually increased the store’s popularity. Customers were recruited through short newspaper ads in evening papers, and from the start, devoted fans were gained.

The concept appealed to the intellectual class, and there were rumors that many regulars were elite civil servants in Kasumigaseki. In 1991 (Heisei 3), the store was featured on television as a place where night-visits were possible, gaining explosive popularity.

The idea of just watching a sleeping woman was inspired by two literary works: Sleeping Beauty by Yasunari Kawabata and The Key by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, conceived by a staff member who had taught Japanese in junior high school.

Sleeping Beauty depicts humanity’s fundamental desires and loneliness. The story, also popular overseas, has been adapted into films and operas. In it, an elderly man is allowed to sleep beside a young woman sedated with sleeping pills, reliving memories of past women—secret lovers or affairs—within a private space where pranks and sexual acts are forbidden. The sleeping girl acts as a catalyst to evoke the man’s youthful memories, highlighting the sadness of aging.

The Key portrays an age-gap couple secretly reading each other’s diaries, using jealousy as a stimulant for sexual activity. When published, it caused a sensation, debated as either art or obscenity, and is a representative work of Tanizaki’s erotic literature.

What these two masterpieces have in common is the fantasy created by middle-aged men’s obsession with sex. The former teacher who invented the image club likely realized from these works that fantasy can be enjoyable—and monetized. Believing a store like this would appeal to stressed salarymen, he opened the shop. The motivation for opening was to pay off debts.

The first image club’s play—experiencing fantasy while watching a sleeping woman and climaxing oneself—was modeled after Sleeping Beauty and emphasized psychological engagement. The authors of the novels could never have imagined their works would inspire a popular segment of the sex industry.

By the late 1980s, night-visit clubs appeared in Takadanobaba, Tokyo. In this setup, the customer sneaks into a room where a woman sleeps. First, the customer picks up a map from the office, then walks through the streets to a specific apartment room. Upon opening the door, it is pitch dark; holding a penlight, the customer finds the bed where the woman sleeps.

These story-driven performances became hugely popular. Even here, the play remained soft: “The woman does nothing and is made to do nothing. The customer only watches her and pleasures himself.”

[Part 2] goes on to detail the thriving 19th-century image rooms in Paris.

References

Fuzoku Shinka-ron (Evolution of the Sex Industry), Fumio Iwanaga, Heibonsha, 2009

Paris, Shofu no Yakata (Paris, House of Prostitutes), Shigeru Kashima, KADOKAWA, 2013

Love Hotel Ichidaiki, Tatsuo Koyama, East Press, 2010

Postwar Sex Industry Compendium, Keiichi Hirooka, Asahi Publishing, 2000

Sex Industry Chronology: Showa [Postwar] Edition, Koji Shimokawa (ed.), Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2007

Other books and online media

Interview, text, and photos: Akira Ikoma