A Farewell on the Mountain: The Popularity of a Book Depicting the Real-Life Story of a Missing Person

With the popularity of mountaineering, lost-and-found is on the rise.

“This is not just a lost item. These were the belongings and remains of someone who perished on this mountain. Could something like this happen in a familiar local mountain? I was thrown into confusion by this unexpected turn of events.”

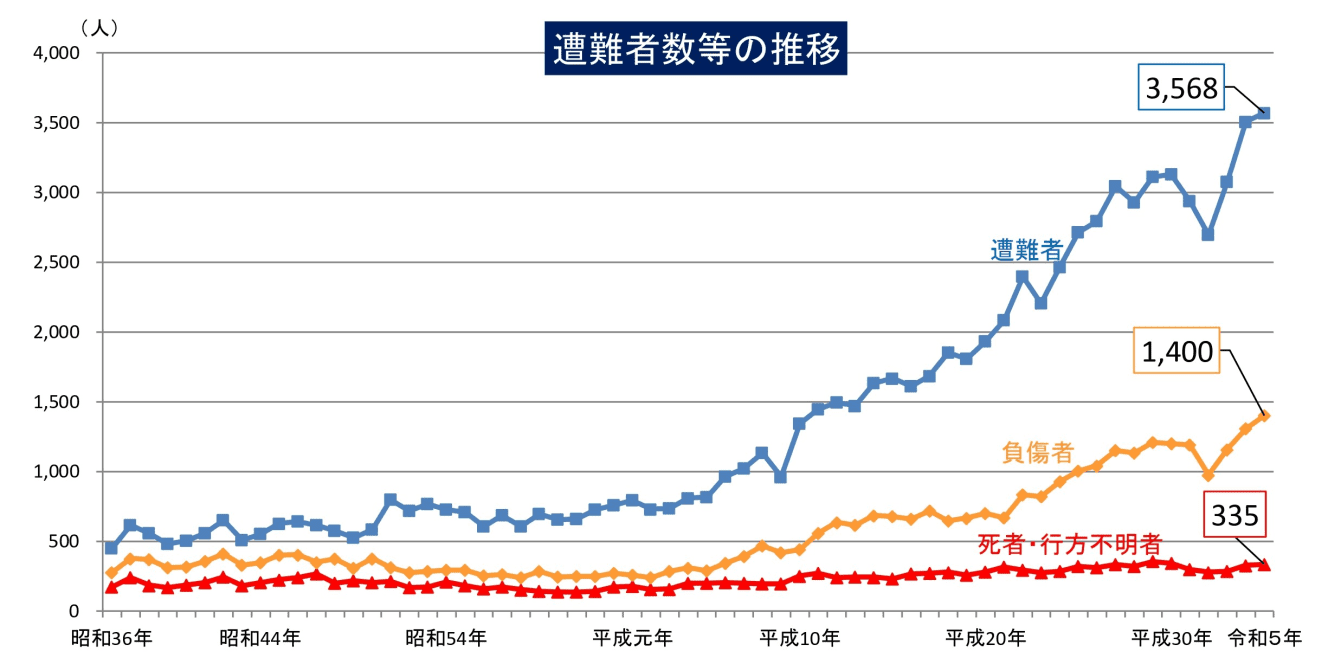

In recent years, mountaineering has gained popularity across a wide range of age groups. With this rise, however, comes an increasing number of mountaineering accidents. According to data released by the National Police Agency, the number of accidents in 2023 reached 3,568, the highest since records began. Among them, 335 people lost their lives, and 42 remain missing.

When we think of mountaineering accidents, we often imagine life-threatening situations in high-altitude mountains such as the Northern and Southern Alps. However, this data also includes accidents that occurred in lower mountains and local hills (satoyama).

For someone like the author, who has no mountaineering experience, the data may not resonate immediately. What does it mean to get lost on a general hiking trail, which people visit for a leisurely walk or water activities? Why are there so many missing persons?

A book that answers these questions is “Until the Day I Can Say ‘Welcome Home'” (Shinchosha), a nonfiction work that has been gaining attention since its release in April two years ago and continues to be reprinted.

The author, Fujimi Nakamura, is a nurse with two children and the head of the private mountain rescue team “LiSS.” In her book, six stories are shared of the team’s search and rescue efforts. Through these stories, readers understand how accidents can happen unexpectedly, even on low mountains or local hills (satoyama), and the heart-wrenching, unrelenting desire of families who just want their loved ones to come home safe.

I spoke with Nakamura about LiSS’s activities and what she hoped to convey through her book.

The reality is that many families of missing persons have given up on the search.

When a mountaineering accident occurs, the first to respond is the official mountain rescue teams from police, fire departments, and other public organizations. However, if the victim is not found during the initial rescue efforts, what happens next?

According to Nakamura, the search by the first responders is typically concluded within three days to a week. After that, the family must either search on their own or turn to private rescue organizations for help.

“Currently, there are two or three private search organizations like ours, but these groups have only been established in the past five years. Moreover, there are 40 to 50 people who go missing due to mountaineering accidents each year, and only about 10% of those cases are handled by private search organizations. In most other cases, families give up searching. If the family is elderly, they may not even know that private rescue teams exist.”

Nakamura’s journey into this world began when, accompanied by a mentor involved in mountain rescue, she accidentally discovered the body of a missing person while hiking. She describes this moment in her book:

“This was the first time I had seen the body of someone who had been dead for three years. What’s more, it was in a mountain that is part of an introductory course for beginners.”

“It was just a little off the hiking trail. I couldn’t stop crying when I imagined that this person had been waiting alone for three years, just off the trail, to be found.”

After this experience, Nakamura was invited to join a private mountain rescue organization, where she began developing her own search methods. One of the techniques she came up with was using her nursing experience to apply “profiling” methods in the search efforts.

Eventually, Nakamura founded the mountain rescue team “LiSS.” She explains the reason behind establishing the organization:

“Before that, I had been participating in searches with another organization. The search process itself didn’t differ much from the official mountain rescue teams, but I often felt something was off. I thought, maybe I should start my own organization and search the way I believe is best.”

What pushed me to take that step was meeting the eldest daughter, M, of a missing person, S, who appears at the end of the book. I strongly wanted to find her father for her, and I came to believe that the best way to find S was to use my own methods, so I made the decision to go independent.”

Utilizing profiling learned in nursing school.

What is Nakamura’s search method?

The primary focus of the first responders, such as the police and fire department rescue teams, is saving lives. They typically conduct their searches in high-risk areas or locations prone to accidents within their jurisdiction.

On the other hand, LiSS, which often receives search requests after the initial rescue efforts are concluded, collects detailed information about each missing person and uses that to guide their search.

Information gathered from the family and friends includes the person’s name, age, mountaineering experience, personality, occupation, as well as hobbies unrelated to climbing, daily habits, conversations before the hike, and what they were wearing on the day of the incident. With all of this information, Nakamura and her team try to infer and analyze the person’s behavior—what they were thinking, which route they might have taken, where they stopped, and what they saw. Nakamura refers to this method as profiling.

This process relies heavily on communication with the family. Since the family members are often meeting Nakamura for the first time, they may not be able to share everything upfront. Building a trusting relationship through repeated, careful questioning is essential.

Using profiling in searches came naturally to Nakamura because of her background as a nurse.

“As a nurse, we create care plans for patients in the hospital. In those plans, we need to understand details like what kind of social life the patient has had, their role within their family, what interests they have, and how they will reintegrate into society after discharge. This involves gathering a lot of information from the patient and their family. It’s something we do every day as part of our job, and I realized that this process could be applied to search efforts in a way that fit surprisingly well. I thought, ‘This could be really useful.'”

However, in search efforts, the person from whom information needs to be gathered is not the missing person but their family and friends. In many cases, families live far away and may not know details like which mountain the person climbed, their exact goals, or what they were wearing when they set out. Gathering this information can be much harder than expected.

“Sometimes, I go to the missing person’s home and ask the family to show me around their house through their smartphone screen. I might ask, ‘Are there any climbing tools there?’ or ‘Do you have any photos?'”

For example, if the family says, “They loved flowers and often took pictures of them,” it might indicate that the missing person took photos of flowers on a mountain. If we can confirm this with hiking companions, it gives us clues about which mountain they climbed and their hiking style.

Additionally, by researching what flowers bloom at that time of year, we can predict the route they might have taken. The process is about gathering even the smallest details and connecting them to form a clearer picture.

It took as little as two hours to find them.

As seen here, while both the official first responder teams and the private search team LiSS share the same goal of searching for missing persons, their methods of searching differ significantly. Listening to Nakamura, it becomes clear that if both teams could work in parallel from the early stages of a search, the chances of saving lives would likely increase dramatically.

In the past, LiSS was able to locate a missing person just two hours after beginning the search. However, the request for their involvement came 20 days after the first responders had concluded their efforts. If LiSS had been able to start the search right after the accident, it’s likely that the person could have been found alive.

“Recently, I think the presence of private search teams like ours has become more widely known, and as a result, we are receiving more requests for searches before the official first responders have concluded their efforts. In some cases, we’ve been approached just two days after the accident.”

Even when conducting parallel searches, Nakamura emphasizes the importance of confirming necessary information through the family and planning the operation to ensure there is no overlap with the public teams. “That planning work is crucial,” she adds.

At LiSS, a coordinator is assigned to manage the search process, usually Nakamura herself. This role also involves handling administrative tasks, such as obtaining the necessary permits from local authorities to ensure the search runs smoothly.

On the ground, teams of two searchers work together. The number of teams depends on the budget, with one or two teams being typical, but occasionally three teams might be deployed.

The minimum daily allowance, including transportation costs, is approximately 80,000 yen. While mountain rescue insurance can cover these costs, Nakamura notes that 90% of the families who request help from LiSS don’t have this insurance. “There’s no such thing as a mountain where the possibility of an accident is zero,” she stresses, encouraging people to invest in mountain insurance.

The length of search efforts has varied greatly. The shortest search took just two hours, while the longest lasted for three years. Throughout this period, ongoing communication with the families of the missing persons is maintained. “Of course, the emotions of the families change over time, so we must be extremely careful in how we interact with them,” Nakamura explains, emphasizing the importance of mental care. “This is a vital part of our work at LiSS.”

“In the immediate aftermath of an accident, the families are understandably desperate for us to search as quickly as possible, so we focus on gathering as much information as we can about the missing person. But as time goes on, the families also need to express their feelings and talk about their confusion and emotions. So, I make sure to listen to them.

As years go by, some families start to feel a sense of resignation. Yet, they still want the search to continue because they can’t entirely let go. We have to honor that, no matter what, and we never give up. Even if we feel stuck, we reset our mindset and keep pushing forward.”

We want to tell the story of the families who are waiting for their return.

The decision to publish the book stemmed from Nakamura’s personal connection with the families of missing persons.

“Many non-fiction works about mountain accidents focus on the survival of the person who went missing, but rarely do they explore the family waiting for their return. How the family spends their time, the emotions they go through, and how they continue their lives afterward are seldom written about. After I was approached with the idea of publishing, I felt a strong desire to share the stories of these families.

However, writing about search efforts involves sensitive content, so I thought it might be difficult to get the families’ consent. But to my surprise, they were all very willing. After the book was published, I received overwhelmingly positive feedback. Many said things like, ‘It feels like we’ve left behind proof that our loved ones were alive,’ which encouraged me greatly.”

When asked what message she would give to those who plan to go hiking, Nakamura offered this advice:

“I want hikers to enjoy their hikes and not experience sad ones. It’s unacceptable for general hikers to die in the mountains. Some people say, ‘I’d be content to die in the mountains,’ but dying in the mountains is never something to be happy about. I hope people will go into their hikes with the mindset that they will ‘make sure to return no matter what.’ If they have a plan for getting back safely, I hope they can enjoy their hikes.”

Nakamura’s words carry significant weight, having witnessed the families anxiously awaiting the return of their loved ones.

▼ Nakamura Fujimi: Representative of the private mountain rescue team LiSS, which conducts search activities for missing persons in mountain accidents and supports their families. International Mountain Nurse (DiMM), Wilderness Medical Associates Japan (WMAJ) Outdoor Disaster First Aid Medical Faculty, and outpatient nurse at the Ome General Medical Center. Nakamura carries out thorough inquiries and search activities while supporting families of missing persons. She also shares information through lectures on mountain search and outdoor first aid.

Reporting and writing: Keiko Tsuji