73-Year-Old Guts Ishimatsu Talks about the Epic Life of the Man Who Changed Japanese Boxing History

This year, history-making mega-fights such as Ryota Murata vs. Gennady Gennadyevich Golovkin and Naoya Inoue vs. Nonito Donaire were held in Japan. Now that it has become “commonplace” for super champions to visit Japan and engage in fierce battles with Japanese fighters, we would like to take a closer look at “that one fight” that brought Japan closer to the rest of the world.

Without that one fight, the Japanese boxing world might not be on the path it is on today.

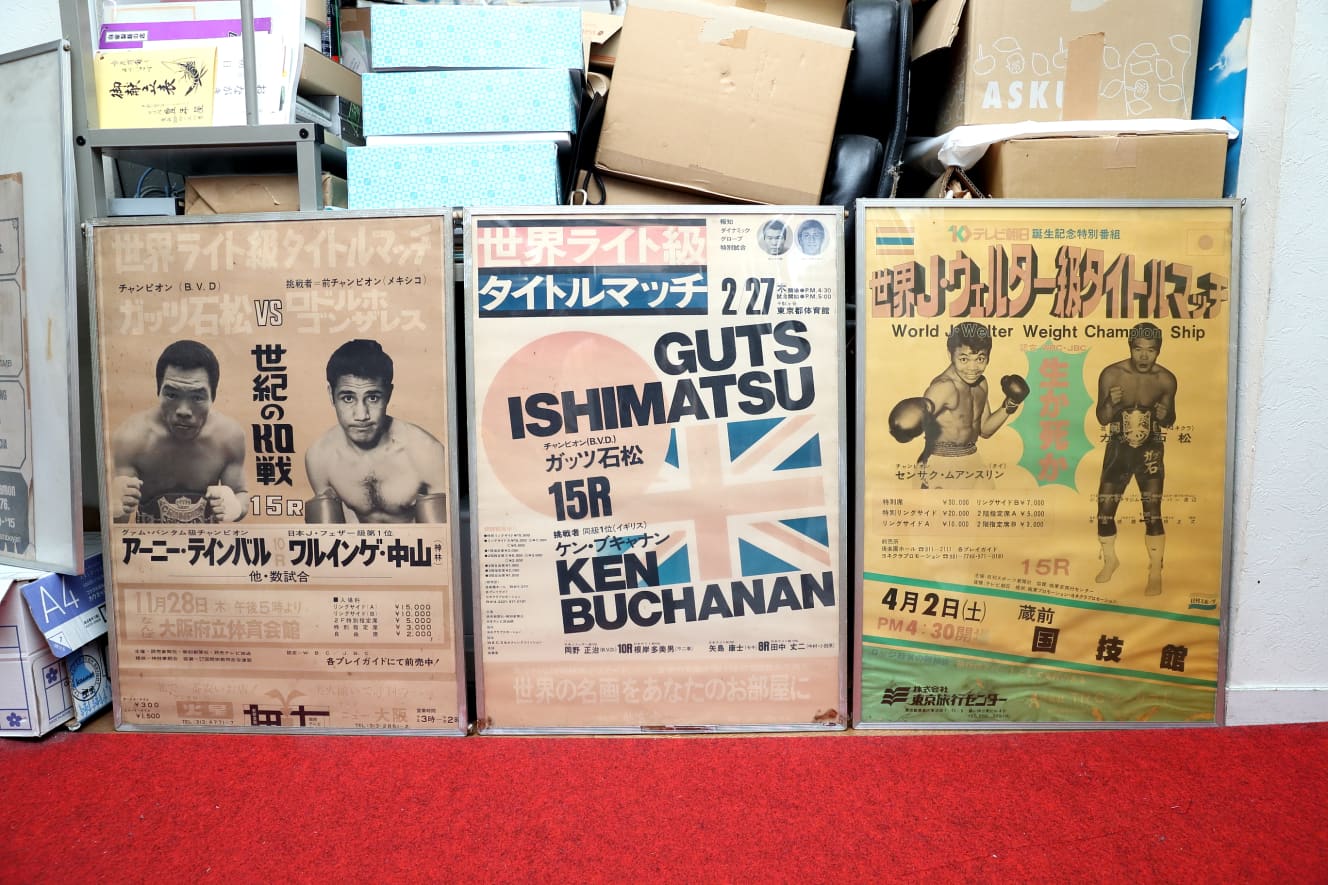

The fight between Guts Ishimatsu and Rodolfo Gonzalez is the one.

The 135-pound (61.2-kilogram) world belt was once considered too high for Asians to reach. The man who broke through that barrier was Guts Ishimatsu, 73, the 12th WBC lightweight champion.

Until he beat Rodolfo Gonzalez by KO in the 8th round on April 11, 1974 to win the title, the idea of a Japanese man reaching the top of the world in the lightweight division was nothing more than a pipe dream.

Ishimatsu later won the green belt that superstars such as Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao wear around their waists, but this fight was not a simple one. The referee made a blatant move to try to get Gonzalez to win by any means necessary.

At 1:14 of the eighth round, Ishimatsu landed a right hook and a left hook that sent the champion Gonzalez down to his knees and to his front. Gonzalez went down for the second time when he ate a right hand and a short left uppercut by Ishimatsu, who came at him to stop him.

The referee, however, claimed it was a slip and pulled Gonzalez’s arm to get him back up. The scene caused a commotion in the auditorium of Nihon University, and the Ishimatsu camp shouted angrily at the referee.

Ishimatsu recalls that day, more than 48 years later.

“The referee was so blatant with his refereeing,” Ishimatsu recalled, “that I thought, ‘That’s enough, but my engine was running. I had no choice but to push forward.”

“I thought it was a disaster, but since I was a kid, I was destined to be like that. Things have never gone straight. What do you do in such a situation? I always asked myself “WHY?” and “WHY?” about society and the situation at hand. Why am I in this situation? I would think about it, and then ask myself, “I see.” I have come up with my own answer. I guess I was lucky to have such an open-minded nature that I could understand that this is the way the world works. What’s done is done. I’m going to beat him again! I’m going to beat him again!”

It was the same in this match. I kept repeating “WHY?” over and over in my head after witnessing the strange refereeing. Oh well, I’m the challenger. I concluded that I had to beat him. Once I got that in my head, it was a straight line.

Ishimatsu, undeterred by the slip of suspicion, attacked even harder, and Gonzalez finally sank to the canvas. No matter how much the referee joined in, it was impossible to continue the match.

Ishimatsu became a national hero in this match. The “guts pose” he raised after his victory became a household word. This was Ishimatsu’s third attempt at a world title, and although he was crowned champion for the third time, he says that it was his second attempt at a world title that changed his boxing career.

On September 8, 1973, seven months before the Gonzalez fight, Ishimatsu challenged the Panamanian Roberto Duran, the WBA same-class champion, who was feared as the “stone fist. Duran was a famous champion who would later win four weight classes: welter, super welter, and middleweight. There is no doubt that this match had an impact similar to that of the Golovkin-Murata fight. Ishimatsu reflected on this historic bout, in which a Japanese fighter took on the world’s super champ.

Duran was very strong and had a lot of horsepower. He was banging, banging, punch after punch after punch. I wanted to say, ‘Wait a minute’ during the fight (laughs). Anyway, he didn’t stop and kept coming forward. I fought like a loser, but after 10 rounds I got tired and fell down myself. I lost that fight because I didn’t have the stamina.

However, without that loss, I might not have become the world champ. I gained confidence from the fact that I was able to fight with such a great fighter, and I also realized what I lacked. In short, I realized that boxing is not about technique, but about physical strength.

What do I have to do to become a champion? Again, it’s ‘WHY? What I learned from the Duran fight was my lack of physical strength. Then I ran about 10 kilometers every day. Actually, I could have become the Oriental champion without running. Still, I started running to reach the top of the world.

Where does Guts Ishimatsu get this “competitive spirit”?

Born and raised in Kurino Town, Kamitsuga County, Tochigi Prefecture, Yuji Suzuki, aka Guts Ishimatsu, is a man who rose from poverty.

I really wanted to be a baseball player. When I was in junior high school, I was in the baseball club and even got a hit from pitcher Yutaka Saotome, who later became a professional baseball player. But baseball costs money. Especially after practice, you get hungry. My friends would bring a nice lunch box, or we could buy milk and sweet breads around the neighborhood to eat, but we did not have that kind of money at home.

Boxing, on the other hand, can be done with just one body, in just one pair of pants, and it doesn’t cost any money. That’s why I chose boxing.

After graduating from junior high school, Suzuki decided to move to Tokyo and join the Sasazaki Gym, where Fighting Harada was a member, but he did not know where it was located. One day, he visited a friend from his hometown who worked at a dry cleaner near Otsuka Station on the Yamanote Line, and was told that there was a Yonekura Gym nearby.

He told me that there was a Yonekura Gym near the station and that I could meet up with my old bad boy friends after practice in Otsuka.

Generally speaking, I guess this was my destiny, but it wasn’t just fate. It’s all about whether or not you can really like the path you choose. You can study because you love it. I can try to be strong. I thought about everything in terms of ‘WHY?’ and grew each time, but boxing was full of WHY?

Why is this movement necessary? How can I become stronger? Boxing is a sport where you have to think about that, and that’s why it suited me. If you practice “just for the heck of it,” it doesn’t matter whether you get stronger or not, it’s okay. People who grow always have a sense of “WHY? Such people have room for growth. Whether or not you can find something that makes you feel “WHY? That is the true dividing line between destiny and fate.

Ishimatsu added, “Of course, my living environment since I was a child also had an influence. Boxing is a sport played by people from poor backgrounds,” he added.

Roberto Duran, whom Ishimatsu fought, also grew up in a slum and survived the rain and dew on a mostly handmade tin roof. Rodolfo Gonzalez, who came to the U.S. from Mexico as an illegal immigrant hiding in the trunk of a car, was illiterate until the age of 18.

I had 11 losses and five draws before I became world champion,” Gonzalez said. In the boxing world, a draw is the same as a loss, so it’s like losing 16 times. If I had the character to give up after losing, I would have been finished long ago. That is why I needed an environment from childhood that would help me develop a competitive spirit.

Whenever I lost, I would ask myself “WHY? When I think about it now, it was a defeat in the process of growing up. I really learned a lot from my losses.

What he thoroughly honed was his left jab.

Not only hitting, but also stopping the opponent. Wait for the opponent to come out and ‘stop’ him with a jab. Then, I would hit him with my best right hand. It took me eight years to make it my own. It was after the Duran fight that I realized that this is what boxing is all about. It took me eight years to find my own style through repetitive practice.

Becoming world champion was a goal far, far away. When I started, I didn’t think I could become a world champion. Every time I played a match, winning and losing, I thought, “What? What is it? As I continued to win and lose, the president of the gym, the gym’s supporters, and people from the TV station started to pay attention to me. They arranged a match for me. Normally, someone who has lost so many fights cannot challenge for the world title two or three times. Yonekura Gym had a lot of athletes, and there were many good ones. If I had one more special power, maybe it was the power to be loved.

He successfully defended his WBC lightweight title five times.

In the old days, boxing was a crush-and-grind, eat-or-be-eaten affair. The gloves were six ounces, and even a jab would send butterflies and papillons flying in front of you. It was different from the way I prepared to get in the ring. I really felt like I was going to get killed. I was really tense, like, ‘If you can crush me, crush me.

After getting out of the ring, he turned his attention to the entertainment industry, as you know.

After becoming an actor, I made it a rule for myself to memorize my lines. It is the foundation of the basics, but the basics are still important. It is just like boxing. I made an effort not to take the script with me to the set. Even if I did, I would only glance at it before the show. In this world, too, the question “WHY? Why did I get this role? I repeated that “WHY?

Another thing I valued more than ever since entering the entertainment industry was civility. When I meet the director, senior staff, camera crew, and other staff members, I greet them with a “Good morning. It is not a sesame paste, but a courtesy. At first, everyone looked at me as “Guts Ishimatsu, the boxer,” but I was low and humble, and I think it was this different image that led them to want to talk to me more, which led to work with me. I was able to meet top-notch people like Ken Takakura, Sugako Hashida, Satoshi Kuramoto, and director Steven Spielberg.

If I had not become a world champion, no one would have taken me seriously, but when I entered the entertainment business, I forgot about Guts Ishimatsu from boxing. I was determined to go into a different world.”

Today, at the age of 73, Guts Ishimatsu makes it a daily routine to take a 40-minute walk around his home.

Even now,” he says, “I ask myself the question, ‘WHY? I think about a lot of things while I walk. Especially these days, there are so many things that really devastate me. COVID-19 crisis, Ukraine being a victim of war, and Japan becoming poorer and poorer… With society changing by the minute, what do I have to do now? Why is there a lack of vitality in Japan today? What should I be doing now so that I myself can live well? I will continue to pose these questions to myself and actively work to find the answers.

On the wall of Guts Ishimatsu’s office is a framed quote.

<Only those who have the bottom line to keep working hard will have the strongest luck in the end.

The scene of his KO of Gonzalez comes back to my mind, and I saw the pride of a man who won the world lightweight title on his third attempt.

Interview and text by: Soichi Hayashi Photographed by: Takeshi Maruyama