Anna Zaitseva Narrates Her Experiences Hiding in a Bunker with Her Baby, Shares Brutality of Russian Soldiers

Anna’s son was four months old when the sun went down. “My son, who was four months old, is sometimes called ‘the symbol of Ukrainian hope. In the underground shelter of the steel mill, my son’s spontaneous nature became a source of emotional support for the displaced people. Thanks to him, we were able to survive.”

Anna Zaitseva, 24, a French teacher from Mariupol in southeastern Ukraine, said.

Mariupol was the scene of the most intense fighting with Russian forces. The Ukrainian military, along with civilians, holed up in the Azovstari Iron and Steel Works, a huge facility with six underground floors that was designed for a nuclear attack, and fought back thoroughly. However, the Russian army declared complete control of the city on May 20, ending the organized fighting. The following is Anna’s recollection of the reality of the war she experienced with her newborn son, and the hope she found in the midst of despair.

“My husband Kirill and I met in early 2021 when we were introduced by each other’s mothers. We hit it off immediately and he proposed to me a few weeks after we met. I still have the wedding photo of the two of us in our wedding dresses that I treasure to this day. However, we were only able to live together for one year.”

Reasons to Regret the Evacuation

Anna’s husband, Kirill, worked at the Azovstari steel mill. When the Russian military attack began, the plant announced that workers and their families could take shelter in an underground shelter, and when a Russian bomb fell near their home on February 25, Anna and her husband rushed to the steel mill with only identification papers and food.

“The car we used to move around was later blown up,” she said. Now I regret very much that we had to evacuate to the steel mill. No one thought that the steel mill would be on the front lines of battle.

In February, my son Sviatoslav was four months old. The people who took refuge in the underground shelter adored him, calling him their ‘angel’. My son was charming the civilians with his smile and cheering up the Ukrainian soldiers. The Ukrainian soldiers brought him powdered milk and diapers. Other evacuated children played with us, and someone would come and take turns taking care of my son.”

Shortly after the evacuation, a major turning point came. Her husband Kirill, a former naval infantryman, enlisted in the Azov Battalion of the Ukrainian SS. Anna vehemently opposed the move, saying she would divorce him. In the end, however, she respected her husband’s decision.

“I opposed fighting because I loved my husband and didn’t want to lose him. The last time I saw him was March 11, when he was in an underground shelter. Now I cannot contact my husband. I saw him leaving the steel mill on a news channel in the (Eastern) Donetsk People’s Republic. I am very worried.”

The bombing of the steelworks by the Russian military intensified day by day. But Anna and her family did not want to leave the steel mill.

“On March 15, about 20 civilians evacuated the steelworks, but unfortunately they were shot by Russian soldiers just as they were leaving the city of Mariupol. Some of them made it to (the southern city of) Zaporizhzhia, but others were forced to return to the steel mill.

Many times there was talk of evacuating to the humanitarian corridor, but each time the Russians reneged on their promise to suspend the fighting. Finally we were able to evacuate on April 30; we saw the sun for the first time in two months. We were escorted out of the steel mill by Ukrainian troops and were met on the riverbank by Red Cross and UN staff.”

Anna and her family were then taken to a sorting camp in Russia. The young Anna was subjected to brutality by the Russian soldiers.

“I was subjected to very unpleasant interrogations,” she said. We were undressed, physically examined by female soldiers wearing rubber gloves, and checked for tattoos and scars. Cell phone information was forwarded to Russia, fingerprints were taken, and photographs were taken.

Finally, all evacuees were questioned by FSB officers. As the wife of a Ukrainian soldier, I was threatened with this. ‘Tell me the truth about your husband’s whereabouts! Tell me secret information about the Ukrainian military.’ I answered nothing. There were representatives of the Red Cross and the United Nations, and I knew that under their protection I would be released.

Russian soldiers also went to the bathroom.

Anna spends two days in a sorting camp. In the sorting camp, she had to be escorted by Russian soldiers even to go to the bathroom. The steel mill refugees who came later were interrogated for more than 10 hours.

“Our interrogation was at night, so the Russian soldiers must have wanted to sleep early, and it only took about four hours.” After leaving the sorting camp, we spent another 24 hours with the Russian soldiers at a school in a nearby village. At night, I heard the Russian soldiers discussing how to kill the Ukrainian soldiers.

I, along with the wives of other soldiers, work together for the return of Ukrainian prisoners of war. We recently sent letters to the Pope and the President of Switzerland asking them to work with the Red Cross to help us. My husband and I only lived together for a year before the war started. It is so hard not having him by my side. I believe that he will come back alive.”

Anna and her young son are currently waiting for her husband’s return.

“When he is older, I will tell him how much he supported me during the hard life in the bunker,” she said. “When he grows up, I will tell him how much he helped us adults to survive the war, even though he was so young. My husband and I love our son very much. We will be with him no matter what happens in the future.”

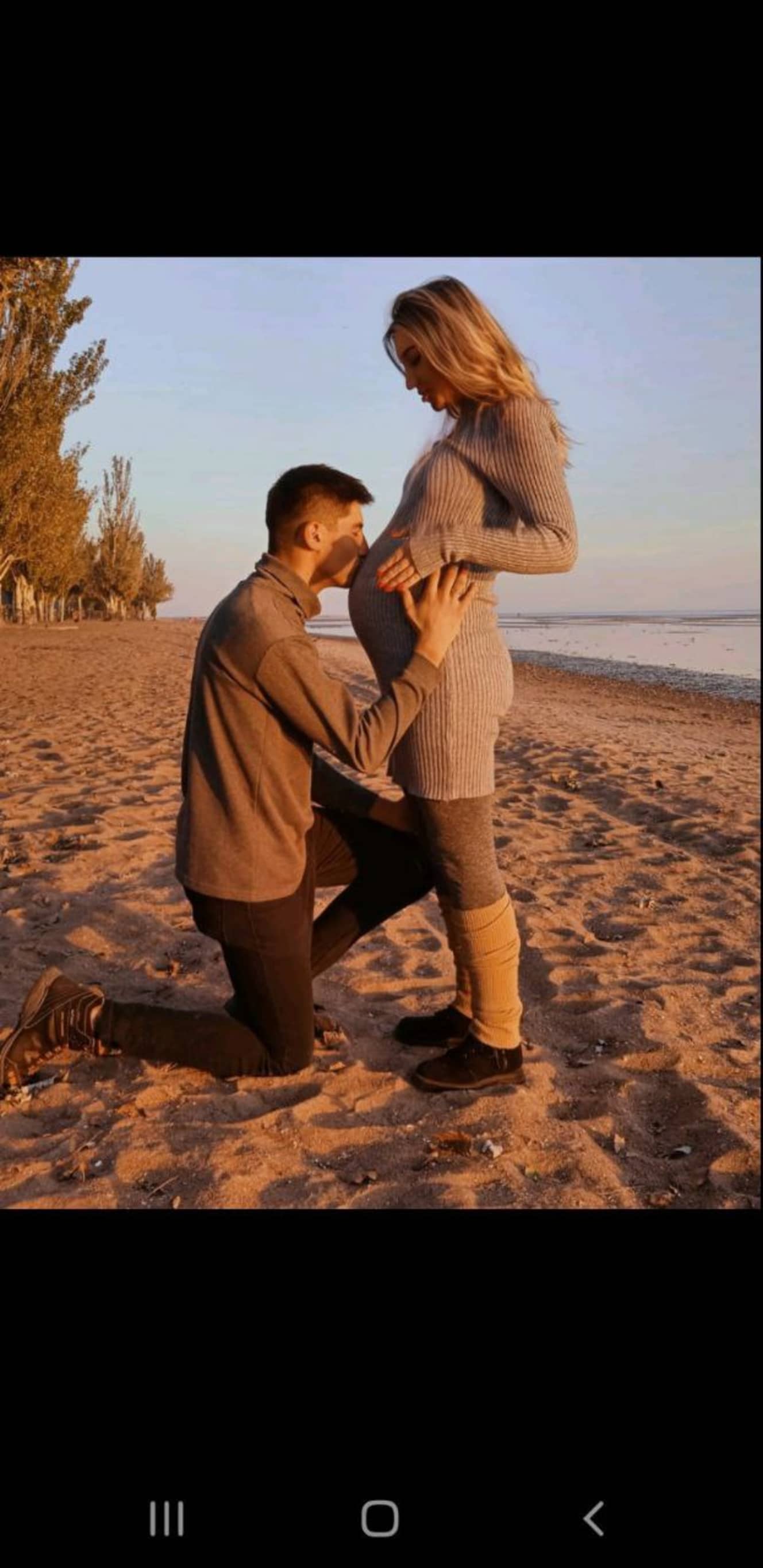

Photo: Courtesy of Anna