Tragedy in Japan 77 years ago…Tokyo Air Raid “Lamentations of War Orphans

Nonfiction writer Kota Ishii delves into the depths of Japanese society!

The world has been greatly shaken by the war that Russia has waged on Ukraine. At this point, there are reports that the death toll from the war is estimated at about 500 civilians and more than 10,000 soldiers. It is also predicted that a large-scale mop-up operation, including air strikes, will soon begin in urban areas. Seventy-seven years ago, on March 10, Japan experienced unprecedented indiscriminate killing in the Tokyo Air Raid.

This The first of these attacks occurred before dawn that day. 300 B 29 The bombers were approximately 2000 Incendiary bombs of up to a ton of material were dropped on downtown Tokyo.

Wooden houses were set ablaze in the blink of an eye, and pillars of flame swirled like tornadoes everywhere, sucking up not only fleeing children and women but also large horses.

Two and a half hours of air raids had 100 million people were affected and about 10 Ten thousand people lost their lives in the flames.

The tragedy of the Tokyo Air Raid has become one of the symbols of the cruelty of war. However, little attention has been paid to the fact that those who survived the air raids, especially young children, had to live with poverty, disabilities, and discrimination for years and decades afterwards.

I am the author of a war nonfiction book, Vagabond Children 1945-. In order to write the book, “The Vagrant Children,” I interviewed and documented dozens of people who lost their immediate families in the air raid and had to live as homeless people, called vagrant children.

From these stories, what does war bring to children? What is the tragedy of surviving war?

Now is the time when the world is shaken by the fires of war. I would like to write down the real voices of children who survived the Tokyo Air Raid.

Their parents were consumed by flames before their eyes. ……

It was around 8:00 a.m., more than six hours after the air raid, when the flames set by the Tokyo Air Raid were extinguished.

At this time, many children had lost their parents, and were covered in ashes, moving left and right. Children who were separated from their parents as they fled, children whose parents were burned in front of their eyes. Some of the children were as young as 2 or 3 years old and were standing still.

Children whose relatives were still alive were found and taken into custody within a few days. But the other children had to fend for themselves.

One of the places where these children gathered was in the underpass of the burned-out Ueno Station, where children and adults who had lost their homes crowded together in the cold mid-March days, fearing they would freeze to death if they slept outdoors without a proper jacket. The first time I saw a woman in the city, I was surprised to learn that she was a woman of the world.

One of the former vagrant children described the scene as follows

There was nowhere to stand. If you went anywhere, even for a minute, you took up all the space, so if you had to do your business, you did it right there. The low-ceilinged underpass already stank so bad, but I remember it was warm and reassuring because so many people were huddled together. But when I woke up in the morning, I found that some people who had been sleeping near the entrance and some sick people had died and turned cold. As I watched, I thought to myself, “This is going to happen to me someday.”

During the war, the government had great power, and soup kitchens were provided. In addition, relatives living in rural areas sometimes received news of the Tokyo air raids and came looking for their relatives living in Tokyo with onigiri (rice balls) out of concern. When they could not find their relatives, they distributed the onigiri they had brought to the vagrant children living at the station and returned to the countryside. This was how they managed to survive.

After the war, the situation changed drastically. First, the number of vagrant children increased. At that time, children were evacuated from the countryside, but in the meantime, their parents were lost in air raids. These children had nowhere to live when they returned to Tokyo, and they became vagrant children.

Furthermore, with the defeat of the war, many people, including military personnel, returned from overseas, causing a serious food shortage. The rationing of food was rapidly dwindling, and the soup kitchens that had been held in the towns were forced to stop serving food.

The children who were forced to obtain food on their own resorted to the following measures

They earned money by shining shoes and selling newspapers at train stations.

Picking and begging on the black market.

Stealing things from stores and U.S. military warehouses.

Helping yakuza or panhandlers for food

Picking pockets or robbing other vagrants.

They eat cats, rats, and crawfish in town.

Some of the children even committed suicide. ……

In this way, you can see that children as young as elementary school and kindergarten age were thrown into the midst of the weak and the strong.

In these situations, the weaker the child, the more disadvantaged he or she is. The younger, smaller, and weaker children, in turn, were unable to get food and had no place to sleep.

One of the former vagrant children said.

After the war, some of the children committed suicide because they could no longer stand the poverty. There were no places to hang themselves and no tall buildings to jump from, so those who wanted to die went to the Sumida River and jumped in. There was a time when I was walking with a friend and he suddenly jumped into the river and died. Another child was run over by a train while lying on the rail. Not many kids tried it, though, because they knew they would be torn apart and eaten by stray dogs.

Even if they did not choose to die, death was close at hand. Another former hobo said, “I was always close to death, even if I didn’t choose to die.

There were kids who went crazy living in the underground passage. One of my friends said he was hungry and suddenly started eating dog shit and blowing bubbles. We all tried to save him, but he just died.”

Just by looking at these testimonies, you can see how harsh the conditions were for the children.

Among the vagrant children, it was the girls who had the hardest time. They could not beat the boys in strength, so they had to either get help from their older brothers, if they had any, or join the boys’ group and take their share.

Also, if they were boys 12 At about the age of 18, they were considered to be in the labor force and could get off the streets by taking live-in jobs. Some children were adopted by families who had lost their male sons in the war.

Girls were at a disadvantage in this respect as well. Girls were not easily needed in the labor force even after they reached junior high school age, and even if they were adopted, they were not in as much demand as boys.

Therefore, girls were forced to turn to prostitution. Most of the ex-vagrant women were tight-lipped, but when we asked the men about it, they uniformly responded with the following answers.

When I asked the men about it, they all answered in the same way: “I don’t think there are any girls, except those who are very young, who say they have never been sexually harassed or prostituted. As far as I know, there are 12 If they were around the age of 18, they were almost always selling their bodies. That’s how the adults tried to take advantage of them, and that’s how the girls had no other way to eat.”

I myself have interviewed street children in many developing countries, and the reality is that few girls and even boys have not been sexually victimized. It is not unnatural to assume that the same thing was happening in postwar Japan.

Because of this background, prostitutes, who were called “pampans” or “night hawks” at the time, were very kind to vagrant children. With the money they earned from selling their bodies, they would treat small children or take them to their homes and take care of them as if they were their younger siblings or children.

One vagrant child was not only allowed to live in the house, but was also taught to read, write, and add. The individual told the following story.

The man said, “Pangpang’s sister told me that if I couldn’t go to school and study, it would be hard for me to survive when I grew up. So she taught me kanji (Chinese characters) and math, and gave me exams when I came home. Without that experience, I think I would have had a lot of trouble when I became an adult. It was a minimal amount of study, but I think I am alive today because of that experience.”

At the bottom of society, there was a structure in which weak people supported weak children.

Those children “now.”

In Tokyo, the sheltering of vagrant children took place mainly between the end of the war and two to four years after the war ended.

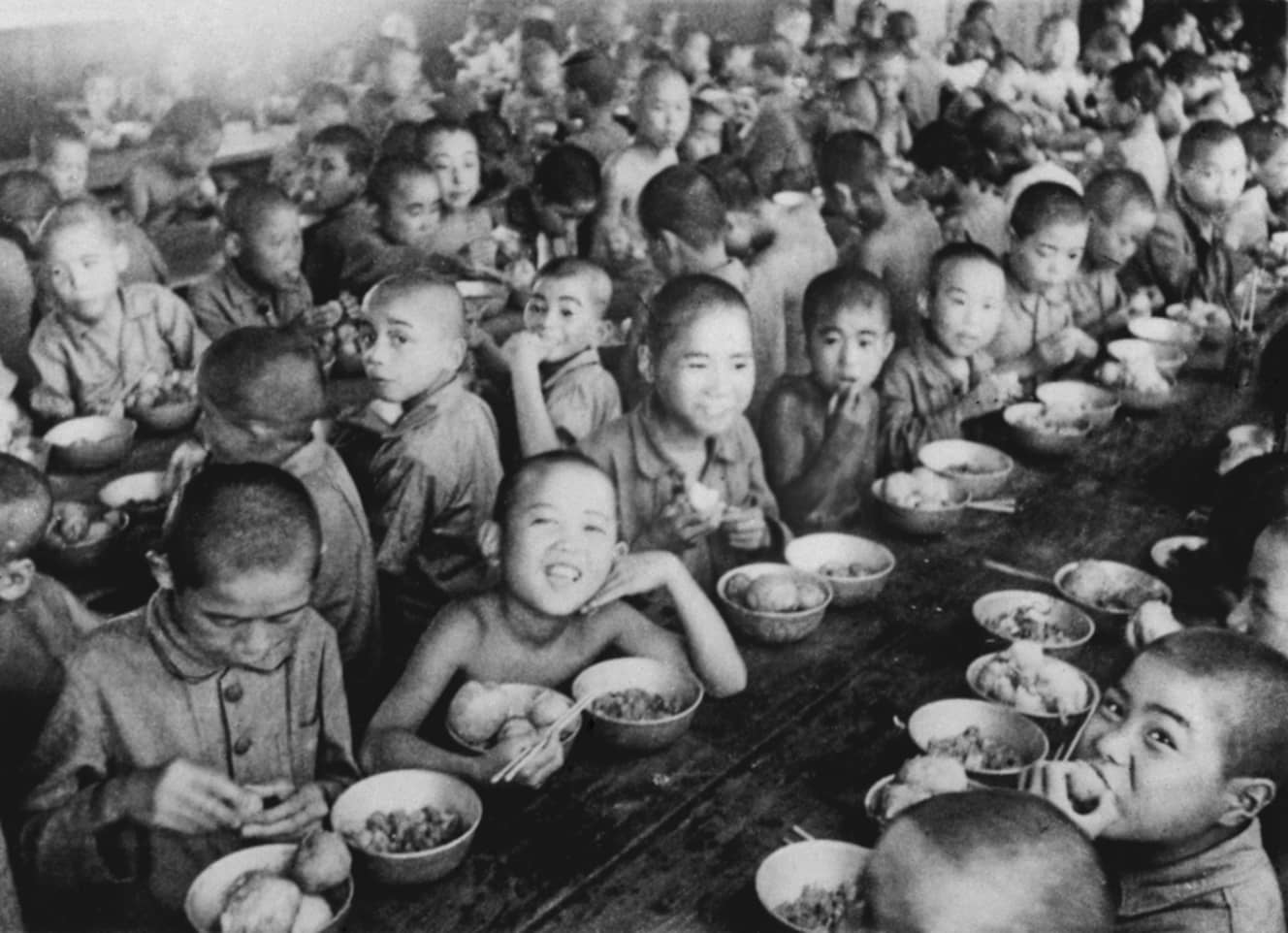

At first, the receiving orphanages (children’s homes) were not well organized or financed, and the children were often abused by the staff or not served food when they entered the homes, so they often ran away. However. 1947 The Child Welfare Law promulgated at the end of the year gradually improved the environment, and the number of children living in institutions increased.

However, this does not mean that the children’s lives have improved. They were socially discriminated against as “orphans” and “former vagrants,” and when they went out into the world to work, they were often disadvantaged because they had no family members who could act as guarantors. For women in particular, their past became a major stain on their lives, and even after marriage, they were forced to hide their past by any means possible.

What kind of lives did these people lead? For more information, please refer to my book “Vagrant Children 1945-. The following is a brief overview of the project. Here we would like to introduce the following testimony.

This is the testimony of a homeless supporter.

He said, “I was a homeless person in the city of 90 In the 1980s, poverty in Japan became a major problem, and homeless support began. At that time, homeless people were in their 60s, and some of them said, “I have been living as a vagrant child since the end of the war. So my life now is just like my childhood again. I must have been living like a homeless person for the entire half century. When I think about it, I realize how difficult life must have been for these former vagrants.

A hobo-turned-gangster tells the following story.

There were many vagrant children who helped the yakuza in order to make a living, and many of them became yakuza. I myself was one of them. When I went to prison, I sometimes met again a vagrant who was living with me at Ueno Station at the time, but who had become a yakuza member of a different yakuza clan and had been caught. There were many people who lived on the fringes of society like that for a long time.”

The person who gave this testimony was a member of the 70 He took his own life in the Sumida River, a year later.

After the Tokyo Air Raid 77 Now, a year later, former vagrant children are 80 Some of them are now in their 20s, but some are still suffering the disadvantages.

In Ukraine and other parts of the world With the war still going on, we must keep this fact in mind.

Interviewing and writing: Kota Ishii

Born in Tokyo in 1977. Nonfiction writer. Graduated from Nihon University College of Art. He has reported and written about culture, history, and medicine in Japan and abroad. His books include "Kichiku" no Ie - Wagakko wo Kajiru Oyasato Tachi" ("The House of 'Demons' - Parents Who Kill Their Children"), "43 Kichiku no Kyoi: In Depth in the Case of the Murder of a Student at Kawasaki Junior High School," "Rental Child," "Kinshin Killing," and "Kappa to Segregation no Shakai Chizu" ("Social Map of Disparity and Division").

Photo: Kyodo News Afro