26 Years after the Incident of Confinement of a Young Girl in Niigata: A Reporter Who Knew the Incident at the Time Recounts the “Media Mania” and “Interaction with the Perpetrator

The “Girl Confinement Case” that Shook the World

The “Niigata Girl Confinement Case” was discovered 26 years ago on January 28, when a doctor and a public health center employee raided the second floor of a private house in Kashiwazaki City, Niigata Prefecture, in response to a consultation from a mother who said that she was troubled by her son’s domestic violence. The fact that this “son,” S (37 years old at the time), who was unemployed and a recluse, had kidnapped a 9-year-old girl in November 1990 and kept her locked up in his room for more than 9 years without being noticed was a shock to the public. Writer Nakahira Nakahira, who worked on the case as a reporter for FRIDAY, looked back at the time the case was discovered and also interviewed the perpetrator about what happened “afterward.

He said, “After I get out of prison, I want to do horse race forecasting for a magazine or something. I also want to help people like myself who are suffering from germophobia. Is there anyone who would be willing to invest in me?”

The man who held the girl captive for about nine years and two months is said to have told a writer who came to visit him at the Chiba Prison about his future.

The shocking incident was revealed on January 28, 2000.

A missing girl was found in a man’s room in Kashiwazaki, Niigata Prefecture.

When this fact was reported on the following day, January 29, a large number of reporters flooded into Kashiwazaki City. The case was called the “Niigata girl confinement case,” and even before the arrest on February 11, the name of the culprit, S., was reported in some media.

In addition to TV and newspapers, many reporters from weekly magazines and sports papers went around S’s home and elementary, junior high, and high school classmates, and their coverage became more and more heated. If a large number of reporters were seeking information, some would think of using it for their own business. One restaurant said, “S was a regular customer and was called ‘Mr. Pervert’ at the restaurant,” and reporters crowded the restaurant every day as customers.

It was unthinkable that S, who was mostly a recluse, would go downtown, but when they thought, “If this is true,” they had no choice but to go there as customers. In the end, it turned out to be a hoax, but one of the evening newspapers asked an employee of the restaurant to draw a portrait of a person who looked like S, and reported it as a “scoop.

The picture of S’s face reported at the time was from a high school graduation album from nearly 20 years ago. Even though it was a crude sketch, there was no reason to say that he was a completely different person.

For this reason, when S was arrested and sent to the public prosecutor’s office, more than 100 reporters gathered in front of the Sanjo Police Station, hoping to get a picture of his face. The atmosphere was heated, with reporters from sports newspapers climbing telephone poles and being yelled at by the police to get down because it was dangerous, and photographers from weekly magazines shouting “S, get your face up,” while S’s face was hidden by a hood, and banging on the window of the convoy.

In the end, however, no one was able to capture S’s face on film. FRIDAY rented an elevated work vehicle on May 23, 2000, the day of S’s first trial, and shot S coming out of the detention center from a high vantage point. However, I was unable to photograph him because he was hidden by a blue sheet.

Pretending to be a concerned party, he entered the house with his mother.

Masaki Kubota, who covered the case as a reporter for “FRIDAY” at the time and continued to follow the case as a freelance writer, was the first person to set foot inside the confinement room as a reporter. According to him, one night around the time the trial began, he was able to make contact with S’s mother for the first time.

That day, five or six companies were in front of my house trying to get a comment from S’s mother,” he said. One or two of the companies pulled out, and around 10:00 p.m., the mother quietly came out. A TV reporter pointed his camera at her, and she froze in surprise. I quickly pretended to be a member of the press, said, ‘Please stop,’ and took her in my arms as I walked to the front door of the house,” he said.

After saying the name of the company at the door, they made some small talk, but did not mention the incident.

Kubota went to see S’s mother again around January 2002, when the first trial decision was handed down by the Niigata District Court. Kubota recalled that time.

It had been about two years, but I remembered meeting her before. S.’s mother was a driving enthusiast, and she and her mother often went on long trips, but because of her fastidiousness, they never ate or stayed overnight, and she rarely got out of the car. She said, ‘I wanted to go to a hot spring at least,’ so I took her mother, the photographer, and the three of us on an overnight drive to a hot spring in Toyama. In the car, I listened to S’s story the whole time.

And then they started going into S’s home. Kubota continues.

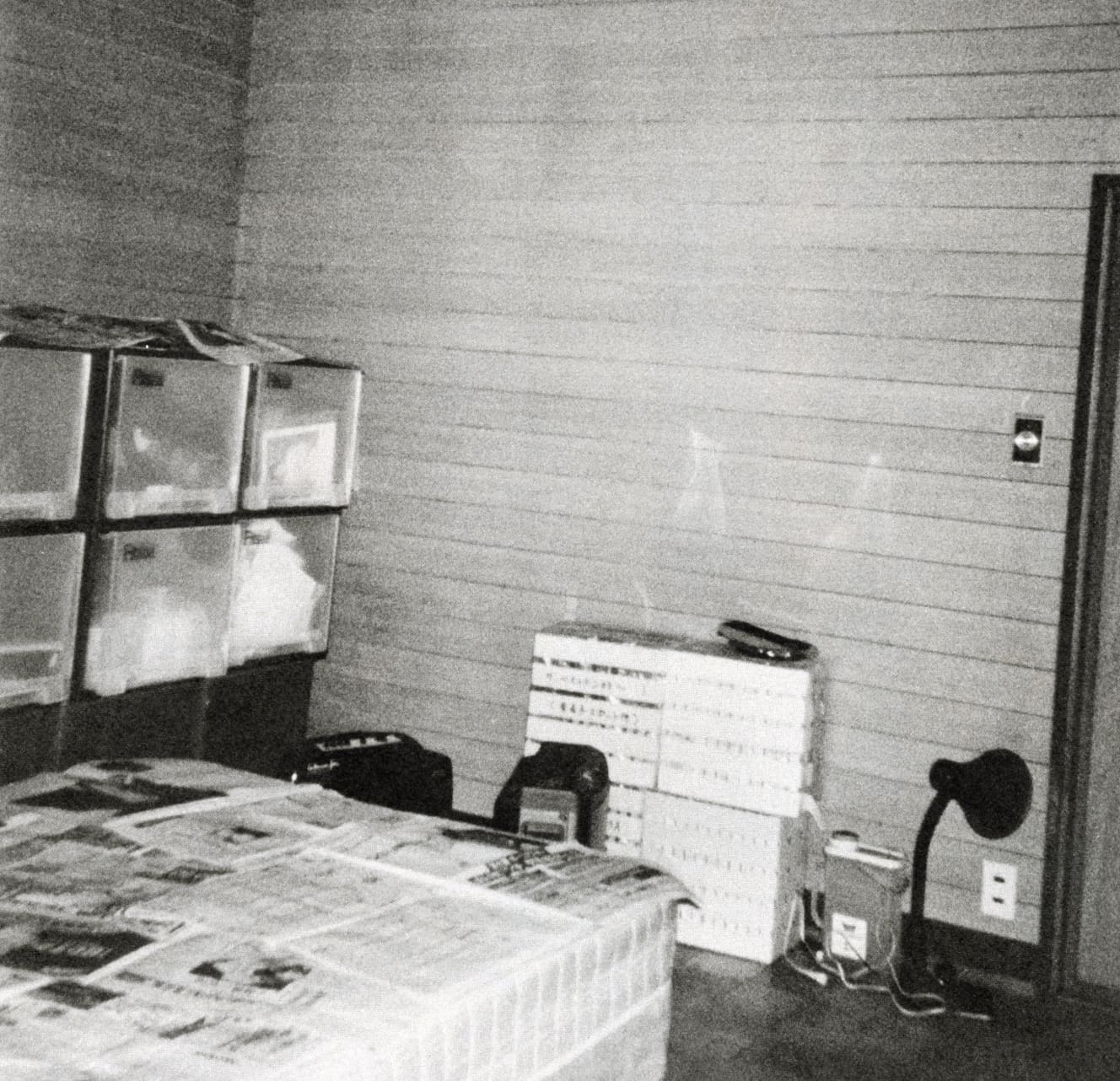

I went up to the second floor where S’s room was located several times. The first thing I noticed was that the paint had peeled off the walls and corridor on the second floor; S had put his urine and other excrement in plastic bags and left them there, so the ammonia had dissolved them.

However, my mother stubbornly refused to go upstairs, because she was afraid that if she even looked up at the second floor, S would tase her with a taser, which was a punishment for being “scared to death. Still, when we finally went upstairs together, he mumbled to himself, “I didn’t realize how small the room was.

I have decided to live my life as a disabled person.”

Kubota repeatedly interviewed S.’s mother and compiled the interviews into a book titled “14 Stairways” in April ’06. However, his involvement with the “Niigata girl confinement case” did not end there. In August 2003, S was sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Kubota recalls the time when he was in prison, and says, “I was in Chiba Penitentiary.

S. was detained in Chiba Prison and read “14 Steps” there. At first, he was angry at me for writing so much nonsense. But as he read it over and over again, he found many things in it that made sense to him, and he told us, “I began to think that perhaps this man Kubota understood me the best of all.

After that, he began visiting S at Chiba Prison, where he listened to S’s complaints about prison and, as requested, offered him idol magazines and car flyers. And as mentioned at the beginning of this article, he also consulted with S about what he would do after his release from prison.

One day, however, the relationship with S came to an abrupt end. Kubota continues.

S was a germophobe and had many problems, such as not being able to eat the same food as the other inmates. As he was repeatedly admitted and discharged from the medical prison, the prison staff, concerned about his condition, assigned a social worker to him. And in discussing with her about what to do after her release from prison, she decided on how to live her life in the future. His last letter said, “I have decided to obtain a disability certificate and live as a disabled person after my release from prison. To do so, I need the help of those around me, so I will no longer see Mr. Kubota, the journalist.

S was released from prison in 2003, and his mother died while in prison. We do not know what kind of life he led after his release from prison.

All we know is that in January 2008, the Niigata Nippo reported that “S died around 2005 in an apartment in Chiba Prefecture. It was pointed out on the Internet that the apartment where he died might have been used for a poverty business.

In contrast to the manic state of affairs at the time of the incident, other companies did not follow up the news of “S’s death” to any great extent.

And now… Twenty-six years have passed since the incident, and S. may have been completely forgotten by the public.

Interview and text: Nakahira Ryo PHOTO: Takaaki Yagisawa