Hieroglyphs Make a Comeback After 1,500 Years, Fascinating Archaeologists

Actually readable from three directions

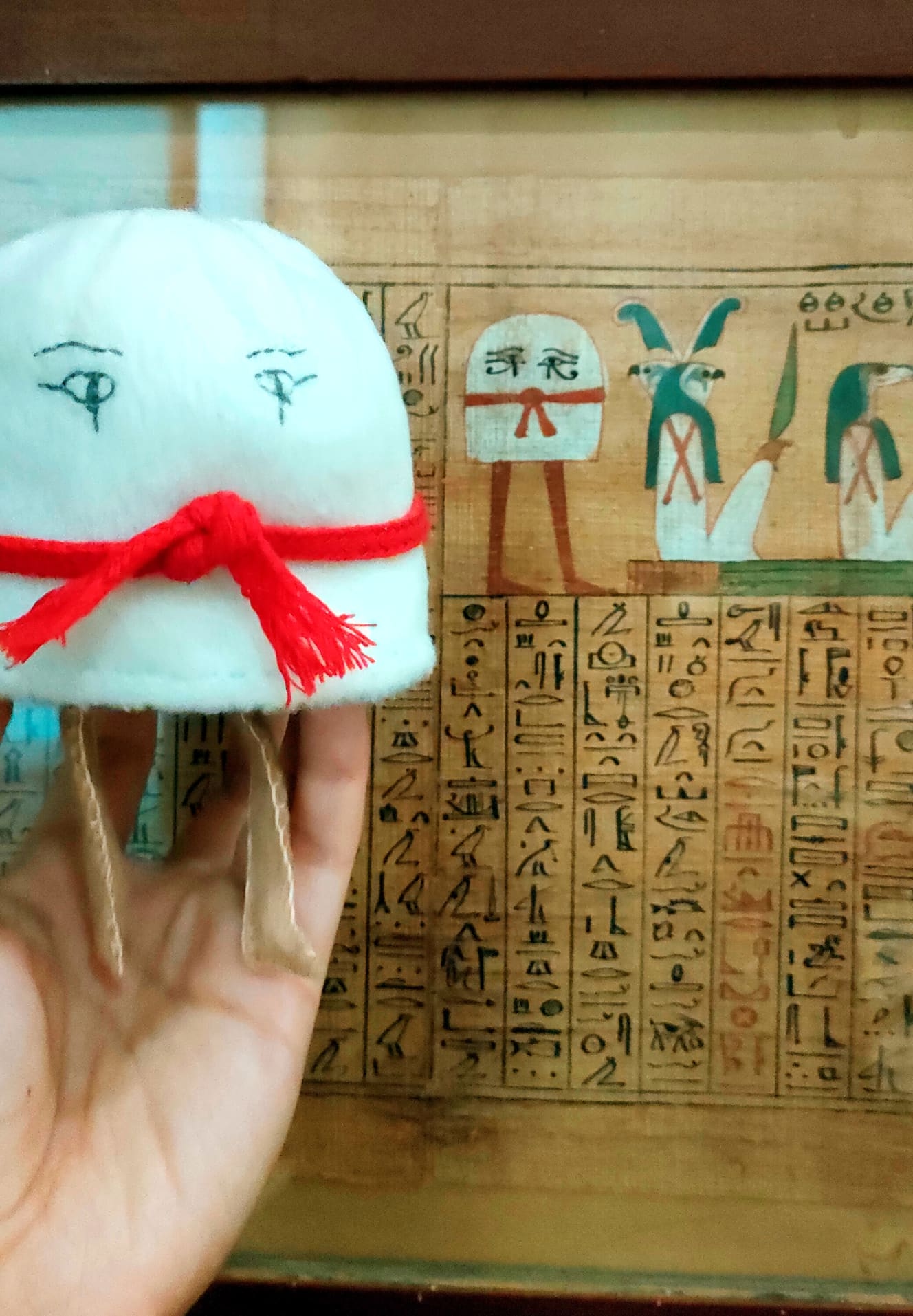

Should it be read from the right, or from the left? Is it a word, or a sound? What do the elephant and giraffe mean──?

Hieroglyphs of ancient Egyptian writing. Owls, eagles, snakes, hands, feet, and other symbols were carved into temples and stone monuments, and to ordinary people, they appear as nothing but codes. But how were they actually read in the first place?

“Some can be read from the right, the left, or from above, in three directions, but the starting point is the animal or human. For example, if a bird’s face is facing right, you read from right to left. These were written when the king issued decrees, and the serving priests and scribes could read and write them. Among the nobility, there were gradations; some could write vaguely, like a foreigner who can speak Japanese but cannot write it.

Even with just birds, there are 30 types of characters, so if a careless scribe writes them, sometimes you can’t tell which one it is or which way it’s facing (laughs). That said, owls, birds of prey, and swallows were commonly used, and context from before and after helps determine meaning. Hieroglyphs function both as pictograms/logograms, which can be understood visually, and as phonograms, like an alphabet.”

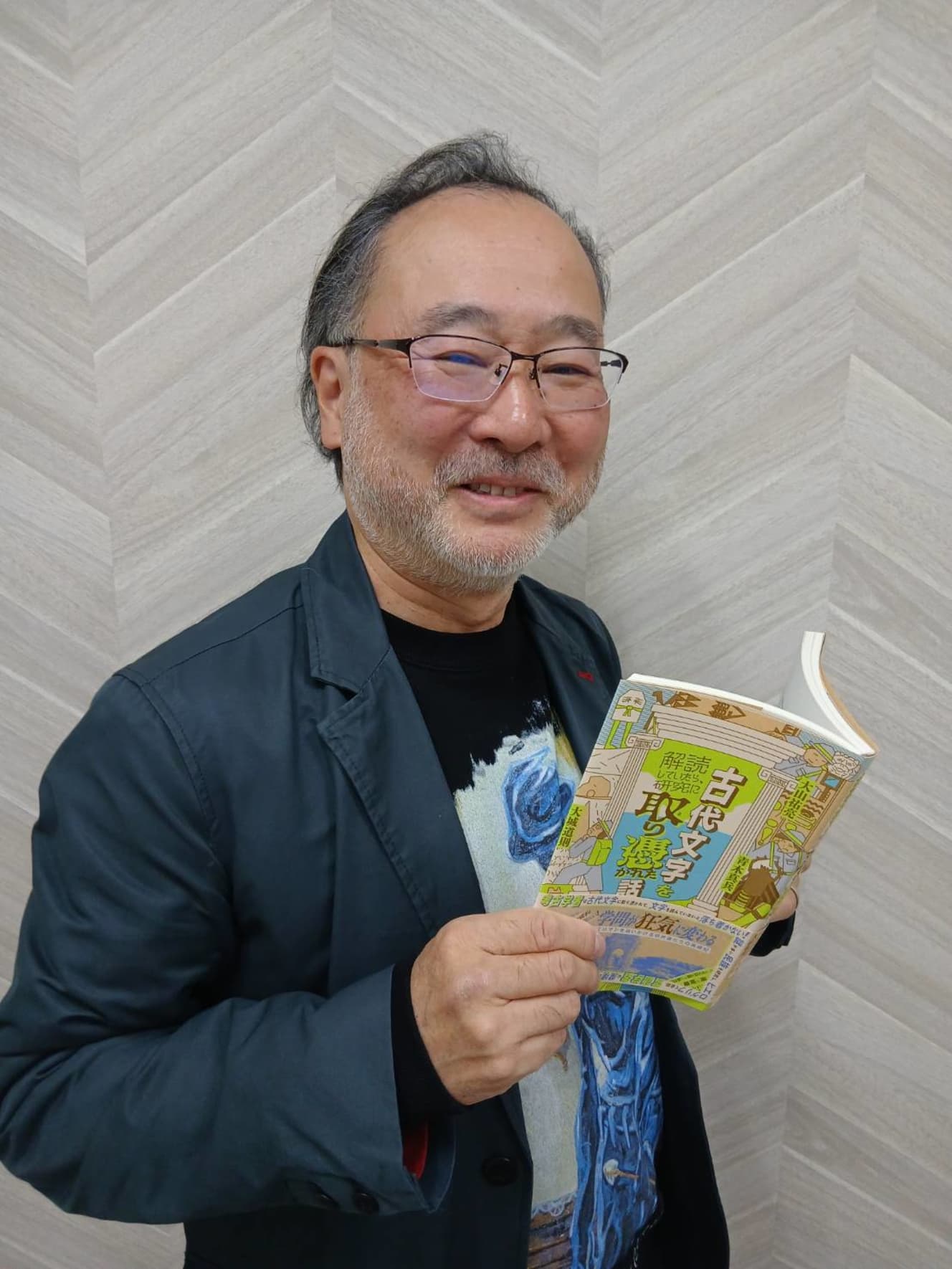

This explanation comes from Professor Michinori Oshiro (Department of History, Faculty of Literature, Komazawa University), one of the co-authors of I Became Obsessed with Research While Deciphering Ancient Scripts (Poplar Publishing).

The period during which hieroglyphs were used was long, spanning roughly 3,000 years, from the 27th century BCE to the 4th century CE.

“Ancient Egypt’s civilization developed, and unlike other ancient civilizations, the literacy rate among common people was high, and the characters used increased over time. However, after the Roman Empire’s invasion, their use was prohibited. In that process, people who could use hieroglyphs disappeared,” said Professor Oshiro (the following comments are also his).

The Rosetta Stone as the Key to Decipherment

By the end of the 4th century, hieroglyphs had completely disappeared. Because their connection to other languages was unknown, they remained a mystery for centuries as an undecipherable script. They became readable about 200 years ago, thanks to the Rosetta Stone, which is now on display at the British Museum. In 1799, the French army led by Napoleon occupied Egypt militarily and discovered the stone monument. In 1801, when the British army defeated the French forces in Egypt, the Rosetta Stone and other historical artifacts were handed over to Britain.

“The monument is inscribed with hieroglyphs at the top, demotic script (a cursive form of hieroglyphs) in the middle, and Greek at the bottom, using three languages simultaneously. Even if the hieroglyphs could not initially be read, scholars hoped that knowledge of Greek could provide clues to decipher them, and that is how the process of decoding began.”

In 1822, the French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion finally succeeded in deciphering the hieroglyphs. They became the first ancient script to be deciphered, and their appearance quickly became familiar to the public.

At the Khan El-Khalili market, now a popular tourist destination in Egypt, goods related to hieroglyphs are everywhere. Items where people can replace letters with sounds to write their own names in hieroglyphs are popular, with pendants being the top-selling item. Incidentally, Professor Oshiro taught Japanese gags to street vendors in a distant Egyptian market.

“When the vendors realized we were Japanese, they would try to attract customers by saying lines from Showa-era commercials, like ‘Bazaar de gozaru’ and ‘Yamamotoyama.’ When I told them, ‘That’s a bit old,’ they asked, ‘What’s popular in Japan right now?’ On the spot, I taught them ‘Goigoi-suu.’”

Even if you can read them, they’re practically useless

Actress Mana Ashida (21) has also spoken on a TV program about her fascination with hieroglyphs. Though difficult to decipher, they somehow captivate people.

“For an Egyptologist, being able to read them is obviously advantageous, but for the general public, one might ask, ‘What use is it?’—and it’s hard to answer. Even if you can read them, they’re essentially useless.

Still, when I was young, I thought that by studying hieroglyphs, I might be able to engage with the thoughts and culture of ancient Egyptians. I wondered if I could unlock the mysteries of the pyramids, whose purposes and construction methods remain unknown. Precisely because hieroglyphs cannot be easily deciphered, they are loved by so many people as a great mystery.”

There are still scripts in the world that remain undeciphered. The Rongorongo script of Easter Island, known for the Moai statues, has yet to be deciphered—and some say it may never be.

“Some suggest that Rongorongo is similar to the script of the Indus civilization, but the Indus script itself has not been deciphered. Additionally, Easter Island is located on a remote island in the middle of the ocean, far from Pakistan and northern India, where the Indus civilization arose, so it’s unclear how any transmission could have occurred.

Rongorongo, the Indus script, and other undeciphered scripts still exist around the world. Hieroglyphs could be deciphered because the Rosetta Stone contained three parallel scripts, allowing for comparisons. For other undeciphered scripts like Rongorongo, it’s extremely difficult without a comparable reference. It’s even possible they may never be deciphered. But precisely because they are shrouded in mystery, ancient scripts hold an indescribable romance.”

The book When I Was Obsessed with Deciphering Ancient Scripts is filled with the curiosity of researchers fascinated by ancient writing. That spirit of inquiry will surely lead to new discoveries. It’s a book to enjoy this New Year, allowing oneself to forget words like cost performance or time performance for a while.

Interview, text, and photographs by Mr. Oshiro: Daisuke Iwasaki