Inside the COVID Crisis That Nearly Crippled the Delivery Health Industry

Kabukicho at night was criticized as a source of COVID-19, and nighttime foot traffic dropped sharply (2021).

Kabukicho at night was criticized as a source of COVID-19, and nighttime foot traffic dropped sharply (2021).Twenty-seven years since its birth, delivery health services (deriheru) have now become the largest segment of the sex industry in Japan. The unprecedented crisis that threatened the industry’s very survival began with the COVID-19 pandemic in the winter of 2020. This is the first half of the fifth installment of a series in which sex-industry journalist Akira Ikoma explores the history of deriheru.

Delivery Health Workers Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic

Since February 2020, when the threat of the novel coronavirus began to be whispered about, entertainment establishments experienced a decline in customers ahead of other industries. Delivery health (deriheru) services were no exception, with customer numbers dropping and many stores seeing sales cut by roughly half.

The damage COVID-19 caused to delivery health workers was immense. Only regular customers continued to visit, while new clients sharply declined. Ironically, the number of delivery health workers increased. Due to unemployment and business closures caused by the pandemic, more ordinary women entered the sex industry.

Moreover, as store-based sex establishments closed one after another, many workers shifted to delivery health services, causing waiting areas to overflow with women awaiting work. Some stores reportedly had three times the usual number of women waiting. With customers halved due to requests for self-restraint in going out, the growing number of workers led to a clear oversupply.

A married-woman delivery health worker in Tokyo reported days when she drew tea (no clients at all) or had only one client in a day, which became more frequent. Some women went three consecutive days without any clients. Many single mothers with young children were unable to work and earn an income when schools closed.

Unable to earn as expected, some sex workers began juggling multiple stores or side jobs such as non-contact chat work. Others turned to direct solicitation (also called backdoor deals), including private prostitution, sugar dating, or paid drinking sessions, bypassing the store to find clients directly. These practices risked breaking trust with the store and were dangerous, prone to trouble. The pandemic’s impact was so severe that many women had no choice but to engage in these activities to make a living.

However, some women managed to earn reasonably well even during the pandemic. These were the women who had regular clients. Many regulars continued to visit weekly or monthly, feeling “safer with women they know rather than playing with strangers,” helping the store stay afloat even when overall customer traffic dropped.

Attendance among registered workers was prioritized based on reservations and popularity with regular clients. Stores ensured that popular women did not leave due to lack of earnings, even assigning them the few available free customers. As a result, top-requested women were less affected by the pandemic.

On the other hand, women who couldn’t secure regular clients fell into a vicious cycle: “Unable to earn, they moved to another store, failed to earn there, and moved again,” or “Unable to earn in the city, they went to rural areas for work, but oversupply prevented earnings there too.” The pandemic made the divide between women who could earn and those who could not more pronounced, resulting in significant income disparities.

Changes in Customer Demographics

Stores also struggled to respond as their earnings plummeted. At a delivery health (deriheru) in Tokyo, some male staff were laid off, and the remaining employees had their salaries cut by 30%. All shuttle drivers were dismissed, and company staff took on the task of transportation themselves.

While sales did not recover, the remaining staff had to manage operations on their own, prompting a complete review of the administrative workflow. Delivery health work does not require receptionists to handle multiple clients simultaneously; using phones, emails, and messaging apps like LINE, a small team could manage operations efficiently.

In Uguisudani, Tokyo—a neighborhood known for densely clustered on-call sex services—female store owners who could not survive the intense competition and unexpected COVID-19 downturn closed their businesses and began working as delivery health workers at other establishments. Additionally, in Chinese-run delivery health services, Chinese staff returned home due to the pandemic, leaving the roster predominantly Japanese and Thai workers.

Even amid these challenges, some stores did not experience a significant drop in demand. At a certain regional married-woman delivery health store, many cast members refrained from coming to work, assuming they would not earn much due to COVID-19. As a result, women who continued to work at the usual pace, along with newcomers who entered the industry during the pandemic, were extremely busy—so much so that their situation was referred to as a “COVID special demand.”

Once the pandemic began, even love hotel districts across Japan—usually bustling with sex workers and clients—emptied. Foreign tourists also stopped visiting delivery health services. Not only did the number of clients decrease, but the demographic and quality of customers shifted. Pre-COVID, clients ranged from people in their 20s to those in their 70s. During the pandemic, the client base centered on men in their 40s.

Even Ikebukuro’s Bustling West Ichibangai Lies Empty (‘21)

Even Ikebukuro’s Bustling West Ichibangai Lies Empty (‘21)How COVID-19 Changed the Distance Between Clients and the Sex Industry

What increased during the pandemic were the so-called rude customers, who seemed to have nothing to lose. These aggressive clients demanded discounts without hesitation, reasoning that “if you’re open during times like this, it should be cheaper.” They would take the short course without conversing and insist on extra services, saying, “I’m paying, so give me everything.” Some clients even developed real feelings for the workers, or became dangerous enough to be banned from the store. Demanding full sexual services was common, and most of these clients were either single or divorced.

In response, the women—who might usually let such behavior slide—began handing out business cards to these clients to try to increase future bookings.

Conversely, the clientele that disappeared were the “well-mannered, financially stable types.” These were men who had families, stable jobs, and occasionally wanted to enjoy themselves. To protect their children and spouses from infection, they stopped visiting altogether. Such clients typically communicated properly, played respectfully, and did not engage in prohibited or violent acts. In short, the good clients vanished.

The pandemic dramatically altered the distance between individual clients and the sex industry. Some men became obsessed with delivery health services. With life plans disrupted and goals lost due to COVID-19, some clients spiraled into despair and frequented these services excessively. On the other hand, many clients stopped visiting entirely. With income and employment stability uncertain, many could no longer afford leisure in the sex industry. The pandemic eliminated habits of frequenting such services, and for some men, these habits never returned.

The COVID-19 crisis dealt a severe blow to the sex industry as a whole. In Tokyo, it became common for long-established, small storefront health services to shift to delivery health. In narrow spaces, following the widely promoted avoid the three Cs (closed spaces, crowded places, close-contact settings) guidance was difficult, and clients who wanted to avoid close contact stopped visiting.

In store-based establishments, receptionists and other customers meant unavoidable contact with multiple people. Delivery health, on the other hand, allowed clients to enjoy services with minimal contact—one-on-one with the worker. The privacy of this approach also made delivery health appealing, causing some clients from storefront establishments to shift to delivery services.

During the state of emergency, as stay-at-home orders and remote work became widespread, many people spent long hours at home, increasing demand for delivery health services that could be enjoyed without leaving home. Some men even redirected funds they would have spent on dining or travel to delivery health services.

Some stores saw increased revenue despite the pandemic. In Osaka, business travelers sometimes chose delivery health over visiting izakayas, since restaurants were required to close early, often by 8 p.m. This led to more men calling delivery health workers as an alternative.

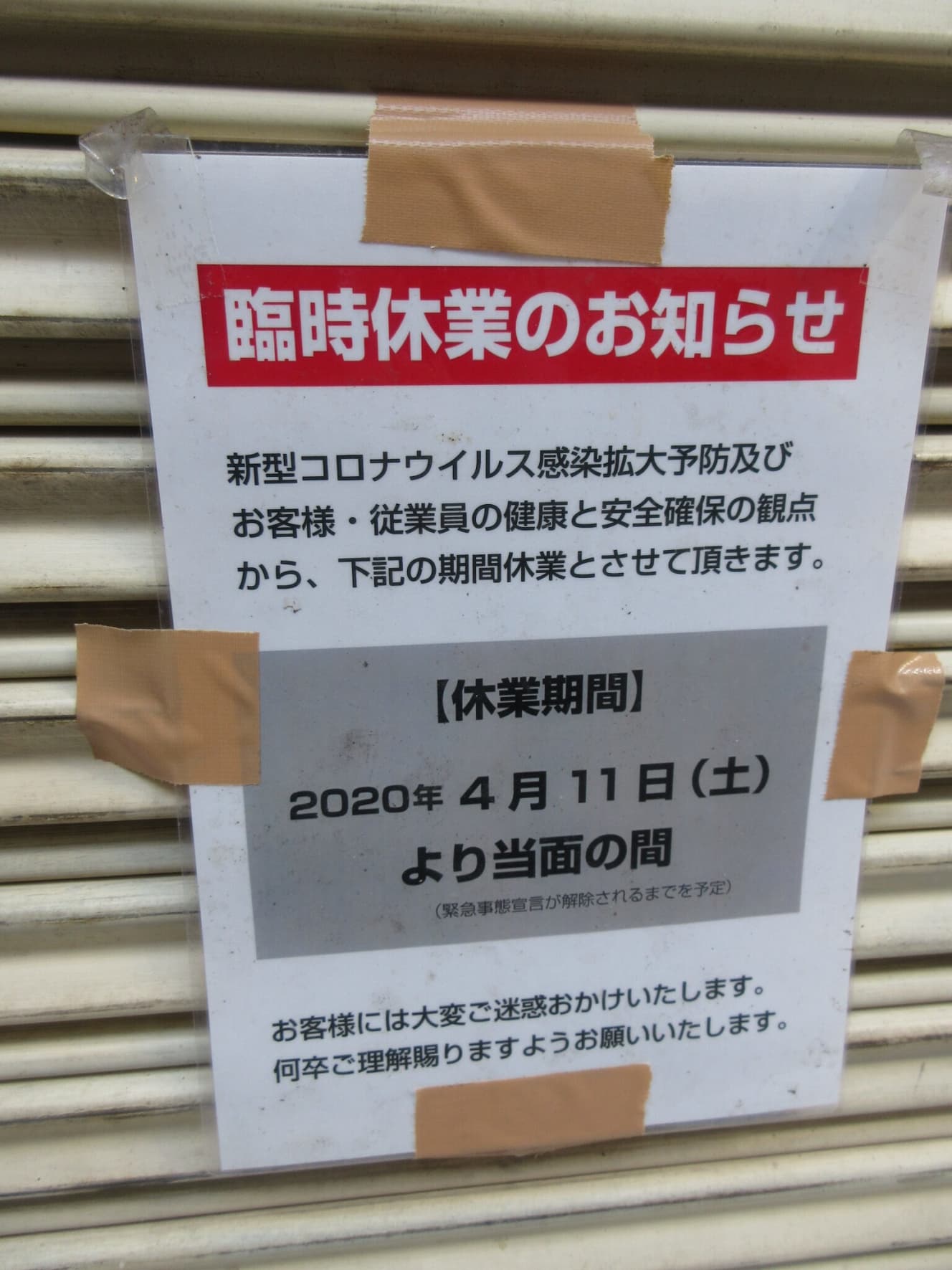

“Notice” Posted at a Sex Establishment Closed Due to COVID-19 (Shinjuku Kabukicho, 2020)

“Notice” Posted at a Sex Establishment Closed Due to COVID-19 (Shinjuku Kabukicho, 2020)Lawsuits Over COVID-19 Relief Funds

During the pandemic, businesses forced to close or suffering significant losses were provided support by the government through rent subsidies and sustainability grants. However, sex industry businesses were excluded from these benefits.

In September 2020, a delivery health (deriheru) operator in the Kansai region filed a lawsuit against the government, arguing that excluding sex industry businesses from COVID-19 relief funds was unconstitutional. The case became known as the “Give COVID Relief to Sex Workers” lawsuit. The lead plaintiff was a woman in her 30s. The plaintiffs formed a legal team and even ran a crowdfunding campaign, claiming the exclusion violated constitutional guarantees of equality under the law and freedom to choose one’s occupation. Nevertheless, the case was dismissed in all courts, including the district court, appellate court, and the Supreme Court.

The courts’ reasoning was that “the sex industry contradicts the sexual moral standards shared by the majority of the public, and it is not appropriate for the state to publicly recognize and financially support the continuation of such businesses”; “it would not align with other policies or gain the understanding of taxpayers”; and “the government is allowed to determine eligibility for aid from a policy perspective.”

This ruling highlighted that occupational discrimination against the sex industry remains in Japanese society. While the pandemic brought hardship to all citizens, government relief was not extended equally. Although the lawsuit ended in defeat, it prompted public reflection on societal prejudice and administrative discrimination against the sex industry, encouraging broader awareness of sex work discrimination.

[Part 2] discusses unique delivery health services born during the pandemic, the current state of the industry, and its future outlook.

[Part 2] Love Doll Specialists and Uber-Style Delivery – The Industry’s Future After COVID-19

References

A Modern History of the Sex Industry by Akira Ikoma, Seidansha Publico, 2022

COVID-19 and Sex Workers by Takaaki Yagisawa, Soshisha, 2021

COVID-19 and Impoverished Women by Atsuhiko Nakamura, Takarajimasha, 2020

Interview, text, and photos: Akira Ikoma