Did a Railway Once Run Here? The Forgotten Tracks Hidden in Our Cities

Just like solving a mystery

“There is a sense of nostalgia in abandoned railway lines—the feeling that trains no longer run there. When you look into how a railway was built there, why it disappeared, actually visit the site, walk it, and talk with local residents, you begin to see the town’s history and culture as well. That’s where the fascination lies.”

So says Masahiro Ishikawa, who explores abandoned railway lines across Japan and introduces them on his self-run website Abandoned Railway Journeys: Travels Along the Tracks. In October, Ishikawa published his book An Exploratory Reader on Urban Railway Abandoned Lines (Kawade Shobo Shinsha).

Although abandoned railway lines exist all over the country, Ishikawa’s book focuses specifically on those in urban areas. The reason, he explains, is that the traces that have blended into local life and everyday living are what make them so appealing.

“Abandoned lines in rural areas eventually return to nature. But in cities, amid rapid changes such as urban development, shifts in logistics, and the undergrounding of railways, traces remain in the form of ordinary roads, promenades, or odd changes in elevation. There’s a kind of fun in discovering them that feels like solving a mystery” (Ishikawa; all subsequent comments are his).

Even when we simply say urban railway abandoned lines, each one differs—in why the tracks were laid, how and why the line was discontinued, and what it looks like today. From the book, we will introduce some of the abandoned lines that left a strong impression on Ishikawa.

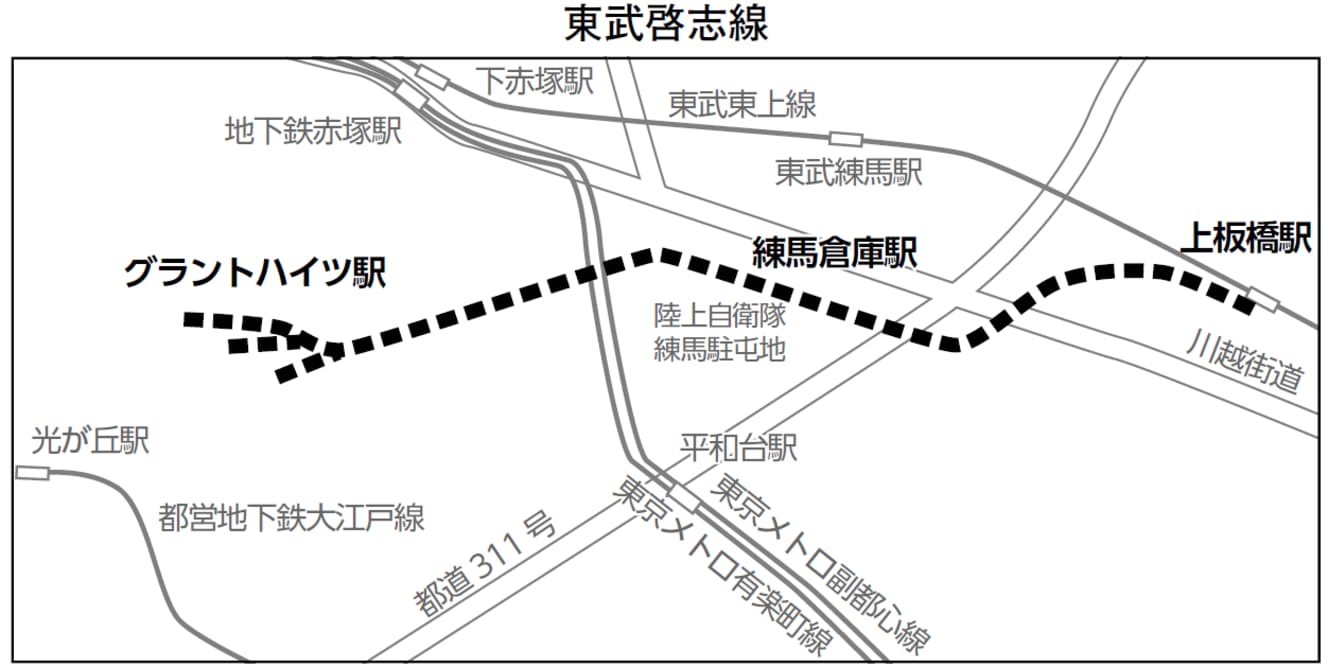

The “Tobu Keishi Line,” locally known as a phantom abandoned line

Hikarigaoka Park, which today spans Nerima and Itabashi wards in Tokyo, is known as the former site of Narimasu Airfield before the war. After the war, it was requisitioned by GHQ, and housing for U.S. military families known as “Grant Heights” was built there.

The “Tobu Keishi Line” was a railway constructed to transport supplies, branching off from what is now the Tobu Tojo Line at Kami-Itabashi Station and running to Grant Heights Station (formerly Keishi Station). The line was discontinued in 1959.

“Locally, it’s known as a phantom abandoned line. Even when you actually visit the abandoned route, sometimes you can’t find anything at all. But when I was walking around while looking at maps and managed to find a single boundary stone—marking former railway land—that wasn’t mentioned in books or online, I felt a real sense of joy.”

Today, materials related to the Tobu Keishi Line, including its rails, are reportedly on display at the museum within the current Nerima Garrison and at the Kitamachi District Community Center near Tobu-Nerima Station.

The “Keisei Shirahige Line,” depicted in Bokutō Kidan

The Keisei Shirahige Line, located in Sumida Ward, Tokyo, was built to enable Keisei Electric Railway to extend into the city center. However, changes in circumstances caused it to lose its purpose, and it was discontinued in 1936, just eight years after opening.

“As I researched further, I learned that Nagai Kafū’s Bokutō Kidan also depicts the lively atmosphere before the line was abandoned and the scene immediately after its closure. That was fascinating too. But no physical traces could be found at all, and even the single remaining trace mentioned in past materials was already gone.

However, at the entrance of a welfare facility newly built on the former site of Shirahige Station, there is an information sign for Shirahige Station. When I spoke with staff at the facility, they told me that the metal pieces on either side supporting the sign were actually rails that had been unearthed during excavation—rails that had truly been used on the Keisei Shirahige Line. To think they survived in that way that made me very happy.”

Communicating with local residents is also one of the great pleasures of visiting abandoned railway sites. Ishikawa says he learned that, in some cases, these abandoned lines have become part of the area’s local identity.

The “Toden Line 13,” which once ran alongside today’s Golden Gai

Kabukicho in Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo, is known as the largest entertainment district in the East, and on its outskirts lies Golden Gai. Running through this area was the “Toden Line 13,” which operated between the area in front of Shinjuku Station and Suitengu. While streetcars once crisscrossed Tokyo’s streets, only the Toden Arakawa Line remains today. Passenger service on Line 13 ended in 1948, after which it was used as a non-revenue line for transferring cars to the Okubo depot. The line was finally abandoned in 1970.

“The promenade called ‘Shiki no Michi’ (Path of the Four Seasons), which runs beside Golden Gai as part of Shinjuku Yuhodo Park, follows the former route of Toden Line 13. Even people who aren’t railway enthusiasts use it casually as a shortcut. At first, I was surprised to learn that such an ordinary place was actually an abandoned railway line. In addition, the municipal Shinjuku Cultural Center across Meiji Street was built on the former site of the Okubo depot, and the oddly diagonal one-way road that gently slopes upward from there is also a remnant of the old railway line.”

Waterside vistas: The Tokyo Metropolitan Government Port Authority Dedicated Lines — Toyosu Lines / Harumi Line

After the war, the freight line between Shiodome Station and Shibaura Station was affected when Shibaura Pier was requisitioned by the U.S. military, leading to the development of Toyosu Pier as an alternative. As a result, the Toyosu Line opened in 1953, and in 1957 the Harumi Line, branching off from the Toyosu Line, began operations. However, as freight transport gradually shifted from rail to trucks, the Toyosu Line was discontinued in 1986, followed by the Harumi Line in 1989.

“The Harumi Line’s Harumi Bridge crosses the waterfront, so the scenery is beautiful both day and night. It was renovated this past September, but before that there was a rusty steel bridge, and the contrast with the surrounding tower apartments was fascinating. After the renovation, it was turned into a promenade and became quite polished, but areas that were previously off-limits can now be walked through, so I think that’s a good thing.

As for the Toyosu Line, only the bridge girders remain, though it seems the bridge itself was still standing until not too long ago. Unfortunately, even these girders may eventually be removed. That said, from the perspective of local residents, such structures might be an eyesore or an inconvenience in daily life.”

Abandoned railway sites must also come to terms with the times and continue to change. They will not necessarily remain forever.

The “Minami-kata Freight Line,” abandoned before ever being used

The Minami-kata Freight Line was constructed starting in 1967 to dramatically increase freight capacity around Nagoya. Elevated viaducts from the project still dot the city today. However, due to Japanese National Railways’ financial difficulties, a decline in freight volume, and noise issues affecting local residents, construction was halted in 1975, and the entire project was frozen in 1983.

“In other words, the Minami-kata Freight Line is an uncompleted line, abandoned before it ever carried a train. It’s a ghost of an unfinished railway. I can’t help but think—after building so much, they just stopped. What’s striking is how the viaduct remains in segments, disconnected. Demolition has started in some places, but removing it costs money, so it hasn’t progressed. Some viaducts even sit atop buildings, and the remaining structures are sometimes repurposed for offices or shops.”

This is an example of an abandoned line whose presence is overwhelmingly tangible, even without searching for traces.

The “Ujina Line,” which even ran on the afternoon of the atomic bombing

The Ujina Line opened in 1894 to connect Hiroshima Station with Hiroshima Port (Ujina) for military transport during the First Sino-Japanese War. Remarkably, it was completed just 17 days after construction began. Later, it was opened to general passengers, supporting Hiroshima’s development. Considering Hiroshima’s history, the Ujina Line played a significant role.

“On August 6, 1945, when the atomic bomb was dropped, Ujina Line trains were hidden in the shadow of a hill, so they were relatively spared from radiation and the blast. According to records, service resumed by the early afternoon that day, and the line contributed greatly to Hiroshima’s postwar recovery.”

After the war, as public facilities moved along the Ujina Line, ridership increased. However, as Hiroshima’s city center was rebuilt, these facilities returned downtown, and passenger numbers declined. Both freight and passenger services were discontinued in 1972, and although a single daily freight train kept part of the line active for a while, the line was completely abandoned in 1986.

“Mazda Stadium, home of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp, was built on the former site of Higashi-Hiroshima Freight Station. The so-called ‘Carp Road,’ where Carp fans in red flow like a wave from Hiroshima Station to the stadium, is built along the abandoned Ujina Line. Researching the Ujina Line shows how it is tied not only to Hiroshima’s tragic history but also to sports, culture, and the city’s spirit—it really gives you a sense of understanding Hiroshima.”

The Ujina Line kept running trains tirelessly during one of Japan’s darkest periods. Even now, its abandoned route continues to support Hiroshima’s citizens in new ways.

Visiting abandoned lines allows you not only to see physical traces but also to learn about their meaning, history, and cultural significance. Side stories emerge along the way.

“I want people, like me, to walk the abandoned routes and discover traces that only they can see, feeling the joy of such discoveries. Every abandoned line has its own side story. The more you investigate, the more you find. I’ve probably only visited less than half of them so far. I’m not even sure if I could visit them all in a lifetime (laughs).”

It seems Ishikawa’s journey along abandoned railways will continue without interruption.

An Exploratory Reader on Urban Railway Abandoned Lines (by Masahiro Ishikawa / Kawade Shobo Shinsha)