A modern proverb, “Don’t drink beer until you puke,” reveals the “daily life” of the ancient Egyptians 4,000 years ago.

Though these words are more than 4,000 years old, they still resonate with me.

Don’t drink beer until you puke.

Sleep the night before you talk back.

The quiet man succeeds, the soft-spoken man fails.

“Dining etiquette is important.”

When and by whom did these sayings originate? It was not Socrates or Plato in ancient Greece, nor Confucius or Lao Tzu in China. They are the words of the ancient Egyptians, far more than 2000 to 4000 years ago. They include not only the words of kings and aristocrats, but also the family precepts passed down from parents to their children.

In ancient Egypt, the level of education was high, and there were classes at school where lessons were copied on papyrus with ink. It was a sophisticated idea that allowed students to learn lessons while memorizing letters.

Some sayings were left on papyrus, others were written on earthenware vessels with hard objects such as bronze or stone, and still others were written on wine jars in prison, and many other useful sayings remain in various forms. Because Egypt is known for its dry deserts, the language is well preserved, and earthenware vessels and jars were not easily subjected to thieves.

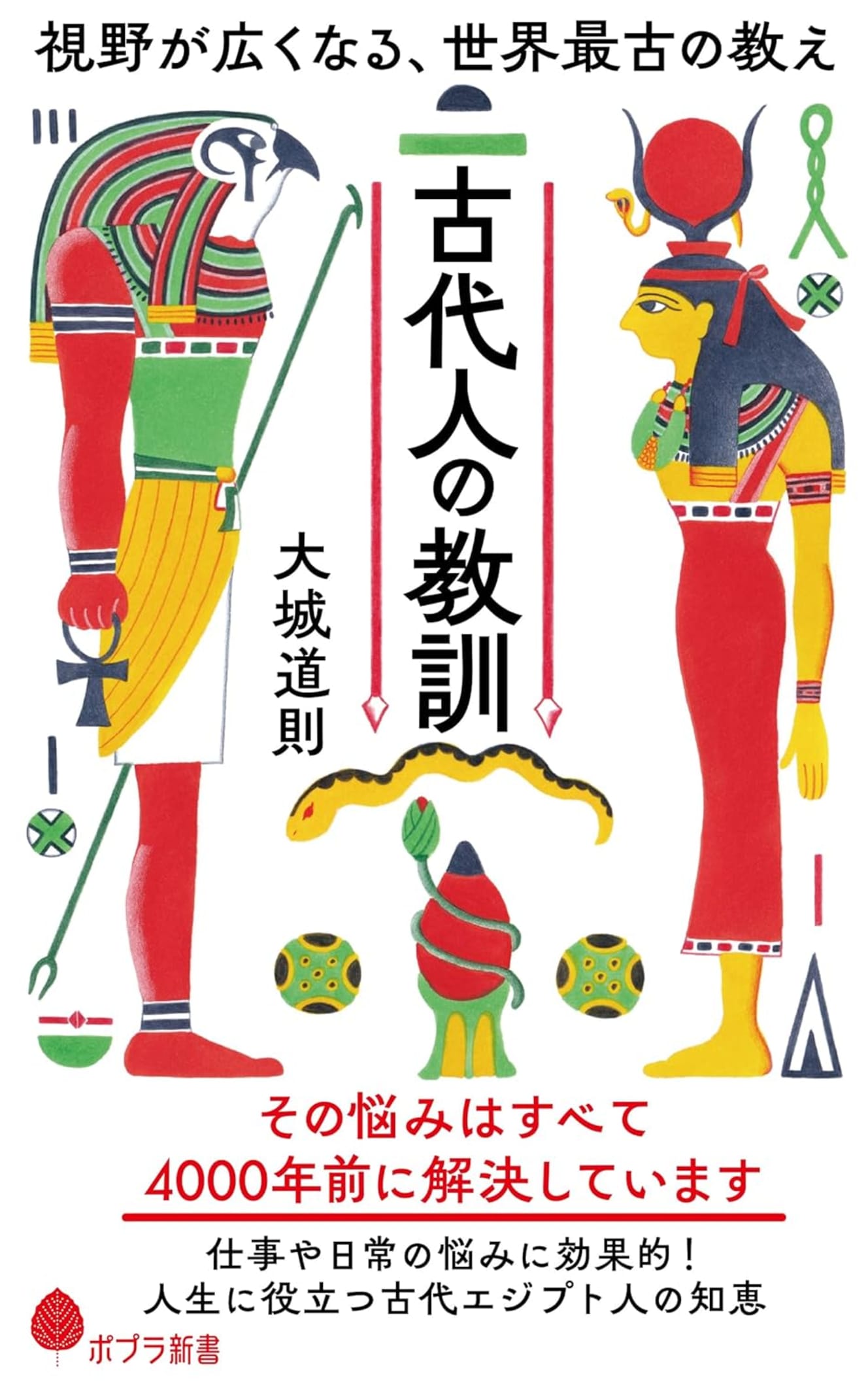

Michinori Oshiro, professor of history at Komazawa University’s Faculty of Letters, and author of “Lessons from the Ancients: The World’s Oldest Lessons to Broaden Your Perspective” (Poplar Shinsho), published in August, explains.

The lessons of ancient Egypt are also applicable to Japanese society in Reiwa. Don’t drink beer until you vomit” will deeply affect anyone who has ever experienced the awkwardness of getting drunk at a later date.

In modern Egypt, 90% of the people do not drink alcohol because of the Islamic faith. However, in ancient Egypt, before the establishment of Islam in the 7th century, there were a certain number of Egyptians who “drank beer until they puked” and screwed up, which is probably why it was left as a lesson. But did beer exist that long ago?

Because of the rich diet, learning also flourished.

The remains of a beer workshop have been discovered at the Hierakonpolis ruins 6,000 years ago, and it is known that beer was produced as a state enterprise. Beer was a safer and more secure drink than river water, which also contained blood-sucking insects.

Hops, the source of the aroma, are not used, so the taste and aroma are different from the beer you may think of, but it also contains a trace amount of alcohol. It was rationed when it was served to those who built pyramids and temples and helped with other national projects.

It was a familiar drink, and even common people could drink beer on a daily basis. Unlike wine, which was only available to royalty and aristocrats, beer was readily available to the people of Egypt 4,000 years ago, and even 4,000 years ago, some Egyptians lost their lives due to excessive drinking.

The saying, “Beer is…” was passed down from the father of the scribe, Ani, to his son in the form of a family precept, and is known as “Ani’s Lesson.

In addition to beer, bread, onions, and garlic were also distributed to those who helped with state business. Egypt had the Nile River flowing through it, as well as the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, which provided an abundance of crops and seafood.

The Nile River valley was the source of garlic, onions, and other savory vegetables, as well as wheat, cucumbers, eggplants, lettuce, watermelons, melons, grapes, and figs. Eels, catfish, and tilapia were caught from the rivers, and squid, shrimp, octopus, and other seafood from the sea, and civilization continued to flourish because of the rich diet. The people were warned not to eat extravagantly so as not to get fat, but in other words, it was because they had a diet that allowed them to get fat. Because they didn’t have to worry about food, their studies flourished.

Other aphorisms remain painful for male readers to hear, such as “Beware of beautiful women” and “Be careful of strangers.

These are not commandments left by the ruling class for the sake of maintaining the system, but rather everyday sayings passed down by fathers to their sons, which is why they are so easily understood by modern Japanese. I am surprised that the parent-child relationship is the same in ancient Egypt as it is in Japan today.

The ancient Egyptians had already found the answers to many of the problems that modern people in Reiwa face in their daily lives and work.

Interview and text by: Daisuke Iwasaki