What’s in the Friendly, Stiff Dictionary that the “God of Dictionaries” Wrote for the Covid-19 Disaster

Japanese language dictionary is a “map of modern language

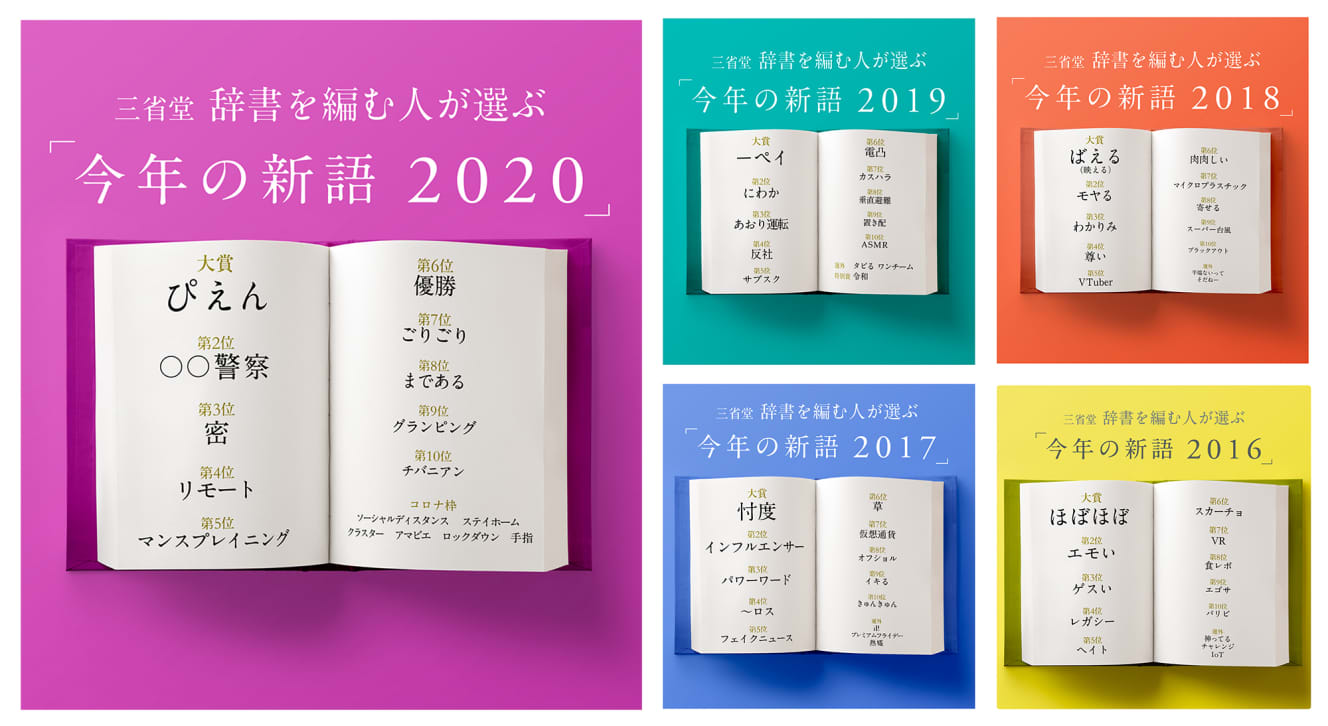

The eighth edition of the Sanseido Japanese Dictionary, the first fully revised edition in eight years, was released in late December last year. There was a lot of talk about the deletion of words such as “MD,” “Stu” and “Kogyaru” that are no longer in use, and the addition of words such as “social distance,” “human flow” and “silent diet” to reflect the Covid-19 disaster, but when you actually look at the dictionary, you will be amazed at the wealth of trivia, etymology and history of words. In fact, I was surprised by the wealth of trivia, etymology, and history of the words.

The dictionary has become more interesting and user-friendly as a reading material. If I were to use an analogy, I would say that it has changed from a serious honors student who simply states the facts to an honors student who is a bit chatty, knowledgeable, and has high communicative power.

Hiroaki Iima, an editorial board member of the Sanseido Japanese Dictionary and a scholar of the Japanese language, says, “The Sanseido Japanese Dictionary has changed the way we think about words.

What the Sanseido Japanese Dictionary is trying to do is to ‘create a map of modern Japanese. Of course we include traditional Japanese. On the other hand, for example, the word ‘yabai’ is now used not only by young people but also by older people. Also, a dictionary cannot be called a “dictionary of modern Japanese” if it does not include words such as “gachi,” which means “it’s really cold today,” and “susuku,” an abbreviation for subscription.

It is often misunderstood that small dictionaries such as the Sanseido Japanese Dictionary are made by extracting words from large dictionaries such as “Daijirin” and “Kojien. But in fact, we have collected and explained words independently. In contrast to large encyclopedic dictionaries of 200,000 to 300,000 words, we have delved into words in the range of about 80,000 words as an everyday language dictionary.

The reason for the inclusion of “tsurami” and “drowsiness” usage is “deep understanding.

As a way to delve deeper, I was surprised by the very detailed nuances of the word “mi,” for example.

The word “mi” is a suffix, and is used for things like “redness,” “yellowness,” “strangeness,” and “gratefulness. In kanji, it is also written as “taste. The suffix “mi” in “pity,” “pain,” “sorrow,” etc. is not similar to this. These are not suffixes, but they have similar meanings.

In addition, another “mi” has appeared since the 2010s. Younger generations commonly refer to “painful” as “tsurami” and “sleepy” as “sleepy. In the past, “tsurai” had only the form “~sa”, but now “mi” is used.

In addition, the usage has expanded to include such phrases as “I want to go there so badly” as “I want to go there so badly” and “I understand very well” as “I understand deeply. I have explained all of these things in this article. In addition, I made a point of saying, ‘In this (common usage), the word ‘taste’ is not written.

The misunderstanding that “totally” means “correct usage with negation

Another word that I think is very modern is the word “totally. Many people have probably learned that the correct usage of the word “totally” is “not at all” with negation. However, the usage of the word has changed over the years.

In addition to the usage with negation, there is also “totally” without negation, such as “It’s totally an accusation” or “My nose is totally stuffed up. This kind of “totally” was used without negation before the war.

However, after the war, the form of “totally – negation” became common. This led to the misunderstanding that only the negative form was correct.

Nowadays, the meaning of “totally” has become more differentiated. It can also mean “by far” compared to others, as in “It was totally fun, unlike the usual classes.

It can also mean ‘don’t worry about it,’ as in, ‘Isn’t this dress weird?’ or ‘No, it’s totally cute. All of these are also explained in the book. To make matters worse, the dictionary notes that it is a ‘misconception spread after World War II’ that negation should be placed under the word ‘totally.

Discovery,” familiar from the Moritomo issue, has an inherently good meaning.

There are also words like “discovery” that are revivals of old words with new meanings.

There are also words like “discovery” that have been revived and changed in meaning. The word “discovery” was originally used in the sense of sensing the other person’s mind, but it can be used without any bad meaning, for example, “to discover my mother’s feelings” or “to fully discover the opinions of the residents. It was a hard word and not an everyday word.

Today, however, the word “discovery” is used not only for guessing, but also for guessing the feelings of influential people and acting in a way to be liked. Moreover, it has become an everyday word.

Looking at the changes in the meaning of the word “discovery,” since the end of the 20th century, new uses of the word have become noticeable in newspapers and other media, such as “a report of discovery to the chairman” and “discovery works. This spread all at once on the occasion of Shinzo Abe’s Moritomo issue and so on. That’s why we’ve added this new meaning to the word.

Nowadays, people tend to think that they can just look up anything on the Internet, but when they don’t know when and when not to, such as when to use multiple Chinese characters, there are many theories on the Internet that can be found on ……, which can be bewildering. Therefore, a major feature of the 8th edition is that it “provides explanations that solve various problems with words in a way that anyone can understand.

The main features of the 8th edition are: “more descriptions of trivia, less subjectivity on the part of the compiler, writing what is generally confirmed or what can be said within the scope of research, based on evidence,” “the ‘two-line principle’ (explanation that gets to the point in two or three lines),” and “description without sparing any material for judgment.

I wanted to make a dictionary that would help people understand what they don’t understand and what they are struggling with.

By showing the current usage and the history that led up to it, I tried to give readers something to think about, so that they can make their own decisions, such as, ‘If there is such a history, I should use it,’ or, ‘It’s fine if everyone uses it, but I shouldn’t.'”

The word “sasete iru” has continued to be used even though it has been called “too polite.

The desire to use honorific expressions as politely as possible has remained unchanged since ancient times. This is why, for example, the issue of “sasete iru” has become a hot topic in recent years.

There may not be many dictionaries that include the word “sasete iru,” but the fact is that it has been used consistently since the end of World War II, even though it is said to be too polite.

The expression “sasete itadakimasu” originally spread after the war because people wanted to be polite, but on the other hand, the politeness of the expression has been criticized. On the other hand, this politeness is being criticized. I’m trying to say things politely so as not to offend people, but I’m being criticized. What should I do? I know you must be wondering.

That’s why I explained the reason why “sasete iru” is used in this article. I’d like you to see the details directly, but there are some verbs that cannot be said as “go~shimasu”. I wrote that “sasete iru” is used as a convenient alternative expression.

Historically, I wrote, “It spread from Kansai to Tokyo after the war, and its use increased at the end of the twentieth century (although there are examples from Tokyo in the early Showa period),” so that the main idea could be understood.

In fact, in the eighth edition, the author tries to avoid using expressions such as “this word is wrong” as much as possible.

In fact, in the 8th edition, we have tried to avoid using expressions such as “this word is wrong.

Dictionaries show that there has always been both ways of using the word. But we don’t actively encourage people to use it, nor do we prohibit them from using it. Our stance is to give you all the information you need to make a decision, and then let the user decide when and where to use the word, whether it is in conversation among friends, in light text, or when we want the reader to feel familiar with the word.

It is not up to the dictionary’s creators to decide that a word is a misnomer and should not be used in any situation.

Especially in the seven to eight years since the 7th edition came out in 2014, people’s linguistic lives have shifted greatly to the Internet. In the seven to eight years since the seventh edition of the dictionary was published in 2014, people’s language lives have shifted to the Internet, which has made people more and more nervous about how to use words, and has accelerated the emergence of the Internet’s “Japanese language police,” who point out that a word is wrong.

Nowadays, the Internet is full of claims such as, “I know you don’t think this honorific is rude, but it actually is! Nowadays, claims such as “You may not think this honorific is rude, but it is! A word that neither you nor the person you are talking to had thought of as rude before, and that everyone had been using normally, can suddenly be slammed on the Internet one day.

When I think a claim is too baseless, I sometimes point it out on Twitter. As long as I am convinced, the other person is convinced, and the words are sufficient to convey the content, then they are functioning properly as a tool. However, on the other hand, there is also the freedom to think, “I don’t want to use it because I don’t feel comfortable with it.

It’s okay to have your own standards. However, the other person may have his or her own standards and way of thinking. It’s better to refrain from simply pointing out that ‘that word is wrong. I would like to emphasize this point.”

Hiroaki Iima, compiler of Japanese dictionaries, was born in Takamatsu City, Kagawa Prefecture in 1967. Graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Waseda University. Earned a doctorate from Waseda University. Member of the editorial board of the Sanseido Japanese Dictionary. Author of “Editing the Dictionary” (Kobunsha Shinsho), “Nihongo wo Motto Tsukumarero! (illustrated by Maki Kanai, Mainichi Shimbun Publishing), “Japanese is not scary” (PHP), etc.

Interview and text: Wakako Tago

Born in 1973. After working for a publishing company and an advertising production company, she became a freelance writer. In addition to interviewing actors for weekly and monthly magazines, she writes drama columns for a variety of media. JUMP 9 no Tobira ga Openitoki" (both published by Earl's Publishing).