Who Said Shoebills Don’t Move? Meet Bongo and Marimba at Kobe Animal Kingdom

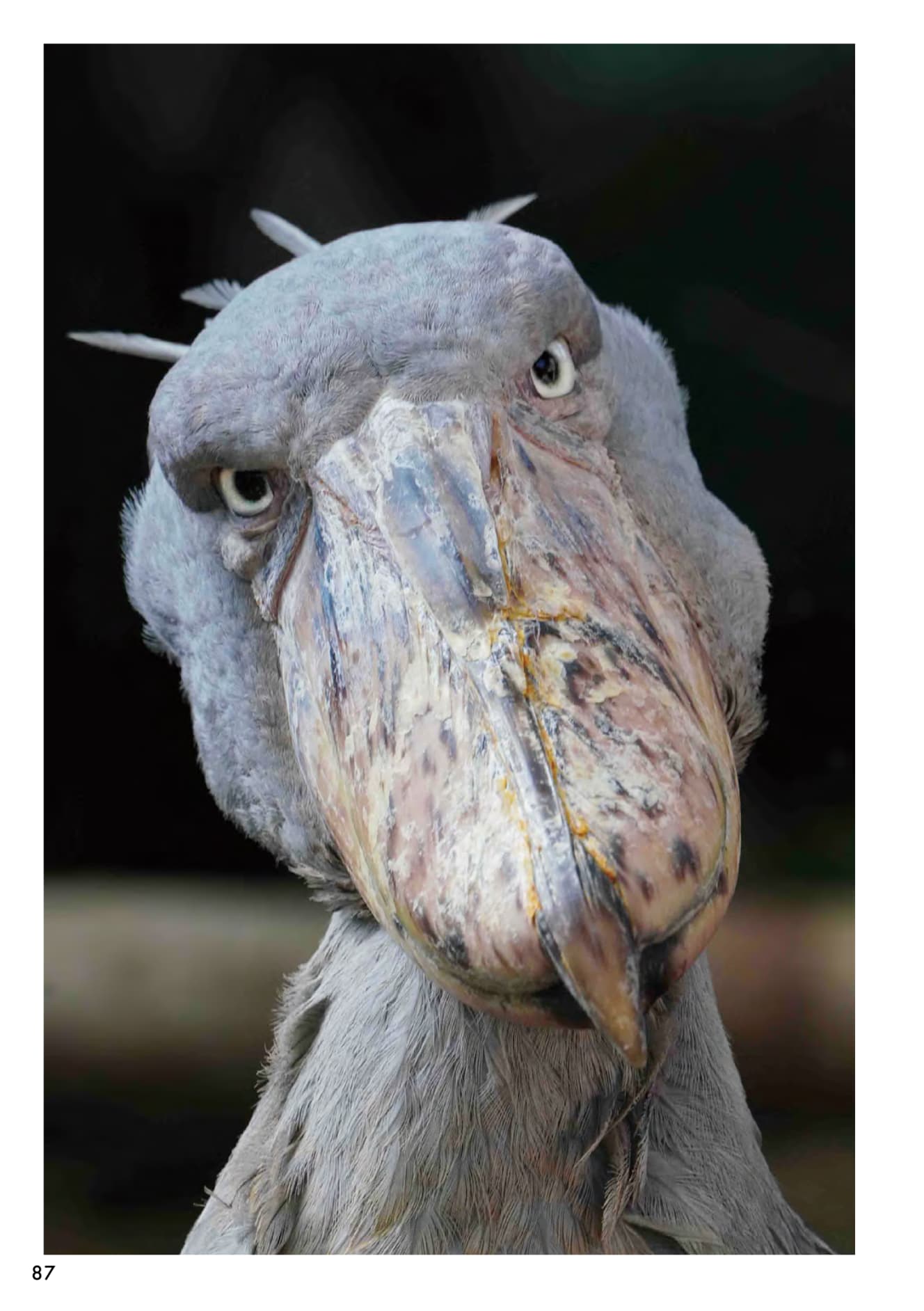

Bongo and Marimba from Kobe Animal Kingdom. Seen from the front, their sharp gaze looks a little intimidating. (From Bongo and Marimba, the Shoebills)

Bongo and Marimba from Kobe Animal Kingdom. Seen from the front, their sharp gaze looks a little intimidating. (From Bongo and Marimba, the Shoebills)The motionless bird that patiently lies in wait for its prey

At first glance, their sharp eyes and large beaks give them an expressionless look. With their sleek, upright stance, shoebills—known as the motionless bird—have become popular on social media and online news. In Japan, 14 of them could be seen across six facilities, but starting July 22, two newly arrived shoebills from the Congo in Africa went on public display at Kobe Animal Kingdom in Hyogo Prefecture, attracting attention.

Shoebills are birds of the order Pelecaniformes that inhabit wetlands in central and eastern Africa. Because their appearance and behavior resemble storks, they were previously classified as belonging to the stork order. They are an endangered species, with only about 3,300–5,300 individuals remaining due to wetland loss and environmental degradation.

They primarily eat fish, and in the wild, they prey on lungfish, which breathe air. With their unique hunting style, they silently lie in wait until the lungfish surfaces for air—earning them the nickname motionless bird. Yet much about their ecology still remains unknown.

At Kobe Animal Kingdom, the long-beloved residents are Bongo (male, who arrived in 2014) and Marimba (female, who joined about a year later). Other shoebills have come and gone, and at times Bongo was moved to other facilities. However, since April 2021, when Japan’s largest shoebill exhibition space, Shoebill Habitat Big bill, was completed to replicate their natural environment, the pair have lived there together (with the exception of a temporary separation period).

A photo book published in April—Bongo and Marimba the Shoebills (by Shunsuke Minamihaba, edited by Kobe Animal Kingdom, published by Tatsumi Publishing)—showcases the pair’s daily lives through numerous photos. Surprisingly, despite being dubbed the motionless bird, many pictures capture them in dynamic poses or even with humorous, expressive looks.

Active Bongo and the slightly timid Marimba

“Both birds move around quite a lot. Depending on the season, Bongo can often be seen circling in flight within the area, carrying nesting material, or approaching Marimba. When Bongo comes near, Marimba tends to run off, but sometimes she’ll later return close to where he is.

Basically, they act independently, but depending on the season, there are times when they interact. During what’s considered the breeding season, Bongo tries to approach Marimba, and some kind of action occurs then. However, the male-to-female communication isn’t necessarily positive.”

—Toshihiro Nagashima, Section Chief, Animal Management Division, Kobe Animal Kingdom

It seems the dynamic is that of an active, male-like Bongo and Marimba, who keeps her distance but is still aware of him. In fact, Marimba is afraid of Bongo because of a past incident where she was attacked, leaving her with trauma. Still, it’s not that they have a bad relationship—shoebills are solitary by nature and only pair up during breeding season.

At the facility, efforts have long been underway to breed these endangered birds, but shoebill reproduction in zoos is extremely difficult, with only two successful cases worldwide—and none in Japan.

“Because there’s no detailed data on breeding, we’re still in the trial-and-error stage. That’s why we collect data on health management, nutritional assessment, fecal hormone measurements, behavioral observations, and activity levels. Ultimately, for breeding to occur, the animal needs to be healthy. We pay close attention to daily health care and each individual’s condition.”

Becoming too accustomed to humans can hinder breeding

They also pay attention to some surprisingly subtle factors for breeding. For example, Bongo has a friendly side and sometimes clatters his beak (a rattling sound used as communication) or even bows to the keepers. However, the staff intentionally ignore such behavior and avoid unnecessary contact with him. They even prohibit walking near the birds while wearing staff uniforms (though Bongo apparently sees through the disguise anyway).

“From a management perspective, it’s fine for the birds to become habituated to the presence of humans, but if they become attached to humans, it hinders breeding. Shoebills may clatter their beaks or bow to people. If we respond and accept that communication, a relationship forms between bird and human, and then breeding doesn’t happen. That’s why here at the zoo, even if a shoebill approaches us with such gestures, we make sure not to respond,”

explains Toshihiro Nagashima of Kobe Animal Kingdom.

Still, whether the shoebills understand the staff’s efforts or not, the distance between Bongo and Marimba shows little sign of narrowing, and the path toward successful breeding remains steep. That is why two new shoebills, one male and one female, were recently brought in from overseas.

“These two are still young, so they won’t immediately contribute to breeding. But they could eventually form a new pair. Now that we have two males and two females, we can also change the pairing combinations, which expands the possibilities.”

With the addition of new companions, how will the relationships unfold inside big bill? Kobe Animal Kingdom’s shoebills are becoming ever harder to look away from.