[Playback ’05] The Disturbing Truth About Predatory Teachers in Schools 20 Years Ago

What was FRIDAY reporting 10, 20, or 30 years ago? In this installment of the “Playback Friday” series, we look back at some of the major topics that made headlines at the time. This time, we revisit the July 15, 2005, issue, published 20 years ago, which featured the in-depth report: “Comprehensive Coverage: 61 ‘Repulsive Sexual Predators’ Who Preyed on Their Students! Exposing the Full List of Charges Against 118 Lewd Teachers at Elementary, Junior High, and High Schools Nationwide.”

Even today, sexual misconduct by teachers remains a serious social issue. Just this June, a group of teachers involved in voyeurism was exposed, leading to the arrest of three elementary school teachers. The article we revisit this time is a 2005 investigative piece by FRIDAY, which independently compiled the actual circumstances of public-school teachers who were subject to disciplinary action due to sexual misconduct (statements in 《》 are from the original article; all ages and titles are as of that time).

118 individuals had been subjected to disciplinary action

[Dismissed Junior High School Teacher (40s), Kanagawa Prefecture]

He was a mathematics teacher and had also served as a student guidance counselor. He would invite his students into his van parked in the supermarket parking lot and indulge in acts such as touching their breasts and lower bodies. In addition to direct indecent acts, he is said to have also had the female students record obscene videos of themselves on their cell phones and send them by email. He was so malicious that he took advantage of the students’ affection for his teacher by saying things like, “If you like it, you can do it,” and in July 2004 he was arrested and indicted on suspicion of violating the Youth Protection and Development Ordinance. It was also discovered that he had committed other crimes against two other female students. He was rearrested.

[High School Lecturer in Shizuoka Prefecture (20s), Dismissed]

In late January 2005, after exchanging emails and texts via mobile phone, a high school lecturer developed a close relationship with a female student and engaged in sexual relations with her at his home. However, when the student wished to continue the relationship and the lecturer refused, she confided in another teacher, leading to the incident being uncovered. It also came to light that between April and June of the previous year, he had engaged in multiple sexual encounters with another female student, both in a car and in hotels. He had essentially been preying on multiple students. The lecturer admitted, “I knew she had feelings for me.”

In addition to this, there were other teachers who, for instance, forced students who made mistakes during club activities to kiss as an apology, or secretly filmed up their skirts with digital cameras during class. Despite this rampant misconduct, the Ministry of Education’s response was notably sluggish. According to the Ministry’s statistics from FY2003, 155 teachers were disciplined for indecent acts—almost four times more than a decade earlier—yet there still weren’t clear standards for what constituted grounds for disciplinary action.

“One of our priorities is to establish that ‘these kinds of actions must not happen in the first place.’ What we’re currently asking each board of education responsible for disciplinary measures to do is create clear standards stating that ‘doing such acts, including indecent behavior, will be grounds for disciplinary action.’ This will serve as a form of deterrence,” said a representative from the Ministry of Education’s Public-School Personnel Division.

At that time, only about half of all school boards had implemented such standards. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, past misconduct was not disclosed publicly, and even teachers who had been dismissed could return to teaching in another prefecture after a certain period. The only real way to protect children from indecent teachers was to remain constantly observant.

The systems are gradually being put in place

Since then, efforts to establish disciplinary standards for corporal punishment and indecent acts have progressed across the prefectures. However, it wasn’t until September 2020 that the Ministry of Education’s guideline—issued back in 2004—stating that sexual acts against children or students should, in principle, result in dismissal finally became a nationally enforceable rule.

Meanwhile, the number of teachers disciplined for indecent conduct has been increasing. While the annual count had hovered in the 200s for several years, it reached a record high of 320 in 2023. Of those, 157 were punished for sexual acts involving children.

As a countermeasure to the growing number of sexual offenses committed by teachers, the “Law for the Prevention of Sexual Violence by Teachers” was enacted in April 2022.

Under this law, teachers who lose their licenses due to sexual offenses are registered in a database. If they apply for reinstatement, a thorough screening process is required. Additionally, schools are obligated to check this database when hiring, significantly raising the barrier for offenders to return to the teaching profession.

Further, in June 2024, the “Law to Prevent Sexual Violence Against Children” was passed. This law includes the so-called “Japanese version of the DBS” (Disclosure and Barring Service). Unlike the previous law, which only covered those who had lost teaching licenses, this system will require background checks for all past sexual convictions (with reference periods depending on the type of sentence), and will apply not only to schools and nurseries, but also to accredited tutoring centers and sports clubs—any job involving contact with children. It will also cover not only new hires but also current staff. The Japanese DBS is expected to go into effect during the 2026 fiscal year.

On July 8, Minister of Education Toshiko Abe revealed that 75% of school corporations running private schools nationwide were not using the database of teachers who had been dismissed. The most common reasons cited were: “We didn’t know use of the system was mandatory” and “We weren’t aware the system existed.”

Even as institutional frameworks finally come together, the awareness and engagement of those who are supposed to implement them still lag behind.

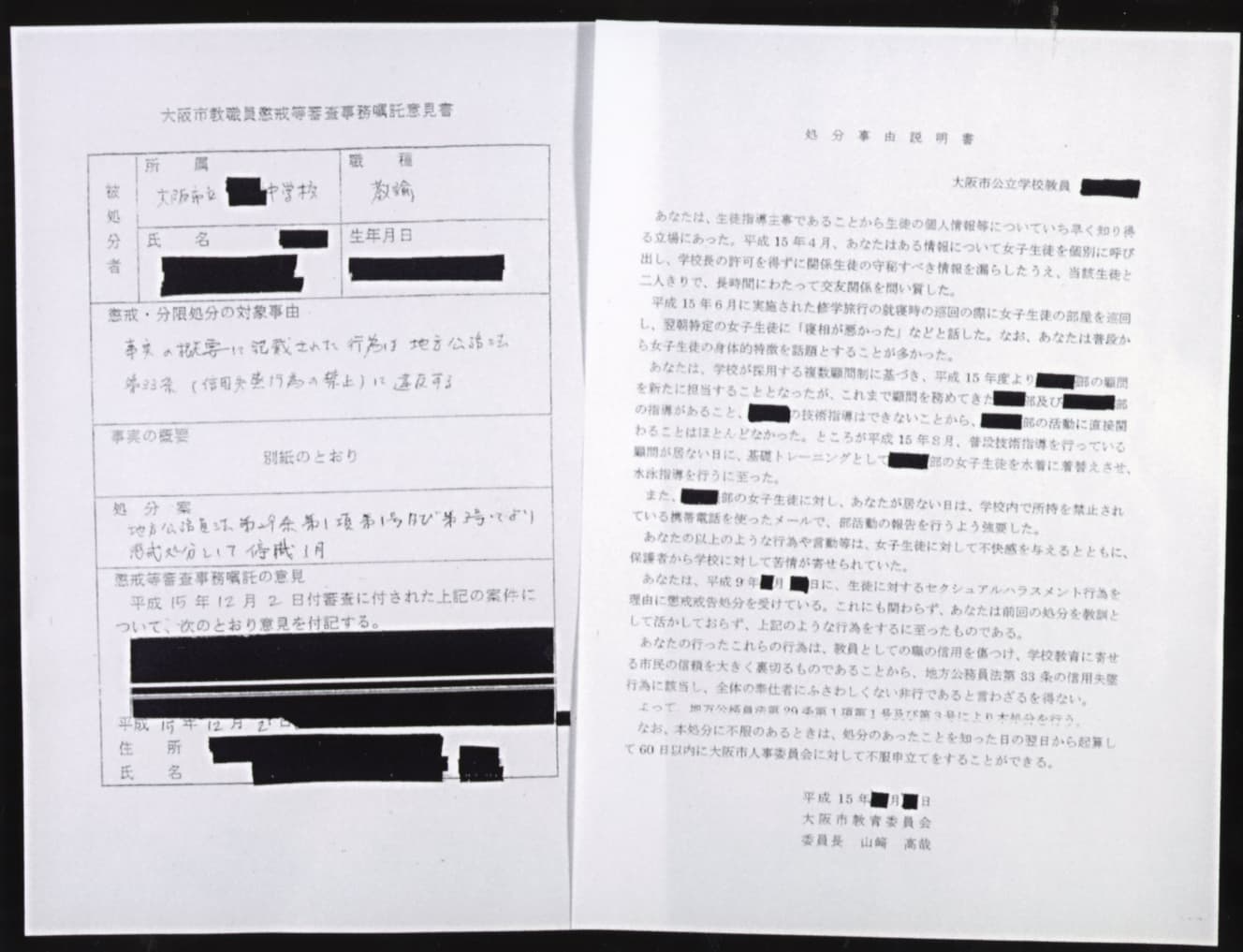

A disciplinary document from a municipal junior high school in Osaka states that a teacher who had previously received a reprimand for sexual harassment toward a student was this time given a one-month suspension as a disciplinary action.

A disciplinary document from a municipal junior high school in Osaka states that a teacher who had previously received a reprimand for sexual harassment toward a student was this time given a one-month suspension as a disciplinary action.

PHOTO: Takeshi Kinugawa, Eirisa Matsui