Prime Minister Ishiba and the Debate Over Consumption Tax and Social Security

A lie that’s been going on for nearly 30 years!?

The issue of consumption tax cuts is heating up as the Upper House election approaches. However, the crucial discussions are not deepening at all. This is because, from the media and journalists to politicians themselves, there is a fundamental lack of understanding about the consumption tax.

Experts point out that one of the biggest and most persistent misunderstandings about the consumption tax is the claim that cutting the consumption tax will reduce social security expenses, calling this a clever lie. Moreover, this lie has been perpetuated for nearly 30 years.

The mistaken idea that it is a correct argument that does not align with populism

With the Upper House election approaching, many opposition parties are advocating for consumption tax cuts, while the government and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party are notably pushing back. For example, LDP Secretary-General Hiroshi Moriyama stated, “The consumption tax is an important source of funding for social security. We will protect it at all costs,” and Prime Minister Ishiba also clearly said, “Since it is a funding source for social security, there will be no tax cuts.”

Similar statements are heard on TV news programs as well. Former politicians turned commentators have said, “I oppose consumption tax cuts because they lead to a decrease in social security spending.” Such remarks are generally welcomed by the mass media as correct arguments that do not align with populism.

However, these various comments merely reveal a lack of basic understanding about the consumption tax.

Prime Minister Ishiba also does not understand the consumption tax

Until now, it was assumed that politicians surely knew this was a lie, but that assumption may no longer hold true.

Prime Minister Ishiba reportedly criticized consumption tax cuts at the Liberal Democratic Party’s national secretary-general meeting, saying, “The rich benefit more from the tax cuts, so inequality will widen.” In response, a professor of political science at the University of Tokyo quickly pointed out, “According to standard tax theory, consumption tax is considered a regressive tax that places a heavier burden on low-income earners. Therefore, the benefits of a consumption tax cut are actually greater for low-income people than for the wealthy.”

Given such a fundamental misunderstanding, it wouldn’t be surprising if he truly believes that cutting the consumption tax would reduce social security spending.

Under the Integrated Reform of Social Security and Taxation, the consumption tax was transformed into a tax dedicated to social security purposes

So why do many people believe that cutting the consumption tax will reduce social security expenses such as pensions, medical care, nursing care, and measures against declining birthrates? The reason is quite simple: they assume that all consumption tax revenue is allocated to social security expenses.

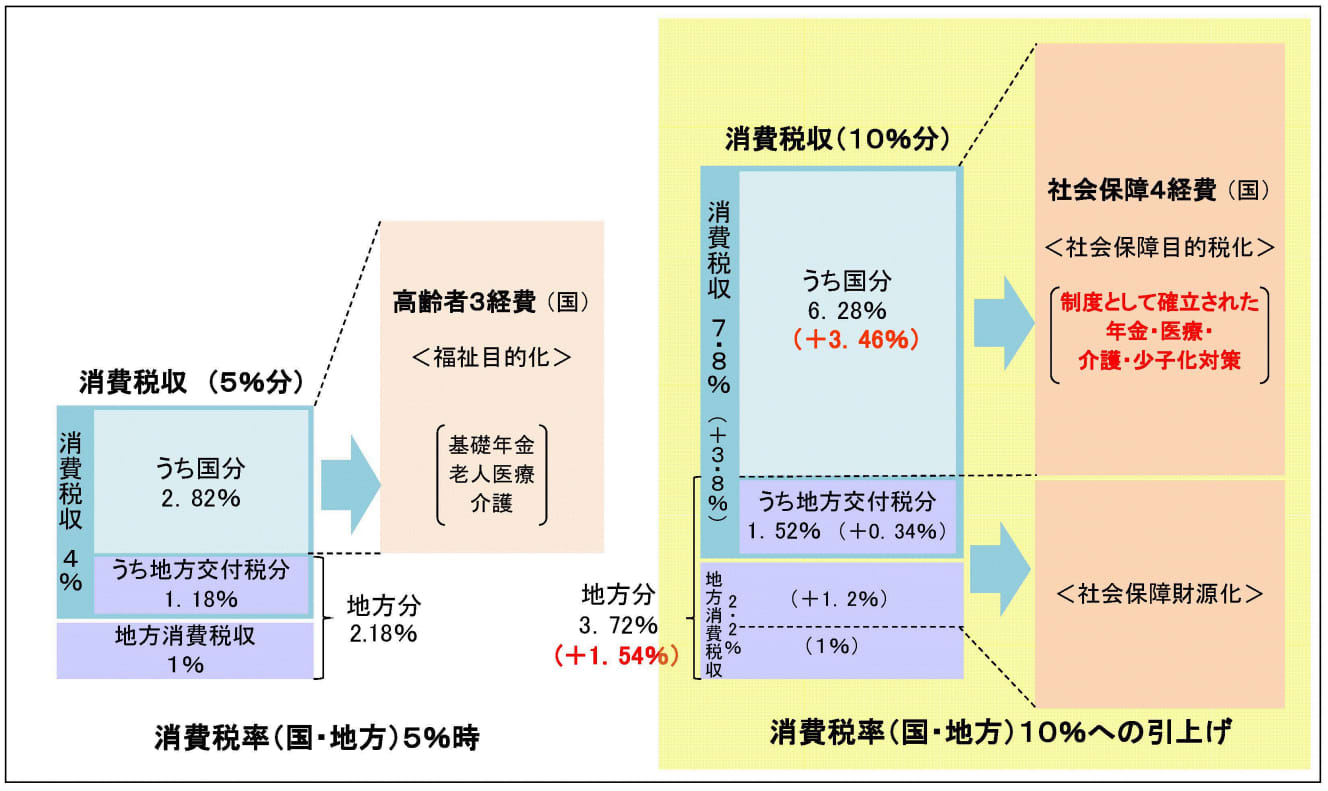

This assumption has a basis. In 2012, under the then-Democratic Party administration, the “Comprehensive Tax Reform Act” was enacted aiming to raise the consumption tax rate and clarify its usage. It was decided that all national consumption tax revenue (national portion) would be allocated entirely to the four social security expenditures—pensions, medical care, nursing care benefits, and declining birthrate countermeasures.

This is known as the “Integrated Reform of Social Security and Taxation” and is added to Article 1, Paragraph 2 of the Consumption Tax Act. Based on this, after the consumption tax was raised to 8% in April 2014, the tax was considered a social security earmarked tax, and its usage was clarified. This is the main basis for the belief.

Reasons why the consumption tax cannot be officially designated as an earmarked tax

At first glance, it may seem unproblematic to think that all consumption tax revenue is allocated to social security expenses, but I want you to realize that such thinking is the result of being brainwashed.

I previously mentioned that through the integrated reform of the social security and tax systems, the consumption tax was converted into a tax for social security purposes, but this does not mean that the consumption tax has actually become a tax for social security purposes. The difference lies in the single character “化” (meaning “-ization” or “conversion into”), which may appear minor in writing, but makes a significant difference in meaning.

To correctly understand this issue, let me first explain the distinction between general taxes and earmarked taxes in taxation.

According to the authoritative tax law text Tax Law by the late Hiroshi Kaneko, a leading figure in tax law, “Taxes levied without specifying their use and allocated to general expenditures are called general taxes, while taxes levied with the purpose of funding specific expenditures from the outset are called earmarked taxes.”

Following this definition, one might think it reasonable to consider the consumption tax as an earmarked tax for social security, but in reality, it is not. The consumption tax is a general tax, just like income tax, corporate tax, inheritance tax, and gift tax.

If the entirety of consumption tax revenue were truly being used for social security expenses, it would make sense to designate it officially as an earmarked tax for that purpose. However, under the integrated reform of the social security and tax systems, the government has only gone so far as to say the tax has been converted for social security purposes and uses the phrasing that it will be used as a source of funding for social security.

Why is that? To give away the conclusion: it’s because consumption tax revenue is also being used as general funding for things like government bond repayments and defense spending. That is the reality, and it’s why the government cannot restrict its use by designating it as an earmarked tax.

The Ministry of Finance’s invented gray area: Conversion into a tax for social security purposes

So then, what exactly does conversion into a tax for social security purposes mean? From the Ministry of Finance’s perspective, it’s likely just a way of saying, “We will treat it as if it were a tax for social security purposes.” In reality, it remains a general tax, but the phrasing is designed to make it look like an earmarked tax—a deliberately vague and ambiguous expression.

What must not be overlooked is the fact that this gray area has been intentionally created to invite misunderstanding. By introducing the unclear and non-standard concept of conversion into a tax for social security purposes, which has no foundation in conventional tax theory, they are effectively encouraging confusion.

Some readers may dismiss this as mere nitpicking, but such ambiguous wording is a textbook example of bureaucratic drafting. They deliberately leave room for discretion, giving themselves leeway to interpret or apply the policy as they see fit.

In fact, even if you refer to the “Outline of the Integrated Reform of the Social Security and Tax Systems,” you won’t find a clear explanation of what this conversion into a tax for social security purposes actually means.

Looking at the Ministry of Finance’s website, under the section “Allocation and Use of Consumption Tax Revenue between National and Local Governments,” you’ll find a chart. In this chart, the national government’s portion of the consumption tax revenue is labeled as converted into a tax for social security purposes, while the local government’s portion is labeled as used as financial resources for social security. However, the outline offers no clarification about the difference between these two terms.

To reiterate: people who believe that all consumption tax revenue is being used exclusively for social security expenses have fallen right into the Ministry of Finance’s carefully crafted trap of misdirection.

Even if Consumption Tax Revenue Increases, Social Security Spending Doesn’t Decrease

Even if the consumption tax has not officially become a tax earmarked for social security, many people might think there’s no need to make a fuss—as long as all consumption tax revenue is being allocated to social security expenses, especially since it’s supposedly stipulated by law.

However, that kind of thinking borders on naïveté—it’s placing too much trust in the government and ruling parties. Let’s go over some of the evidence that contradicts this belief. To begin with, numerous experts have pointed out a basic fact: “Even though the consumption tax was increased, social security spending has not decreased.”

For example, in 2014—when the consumption tax was raised from 5% to 8% under the Integrated Reform of the Social Security and Tax Systems—consumption tax revenue rose to 16 trillion yen, a 5.2 trillion yen increase from 10.8 trillion yen in 2013. Meanwhile, social security expenses rose only modestly from 29.1 trillion yen in 2013 to 30.5 trillion yen in 2014, an increase of just 1.4 trillion yen.

With such a significant jump in tax revenue, it would be natural to expect a corresponding reduction in the burden of social security costs—or at least a larger increase in social spending. But there were no particular factors in 2014 that would justify a sharp rise in social security expenditures. In short, the increased revenue from the consumption tax hike was not allocated to social security. (A look at 2014’s government expenditures shows it was mainly used for government bond repayments.)

Around 2014–2015, there were frequent criticisms along the lines of “The consumption tax was raised, but the money isn’t going to social security!”—but most people seem to have forgotten.

Even the Prime Minister Cannot Claim That the Entire Amount Is Allocated

Using Slush Fund Accounting to Conceal the Use of Consumption Tax Revenue

Despite the many contradictions that have been pointed out, the government and ruling parties continue to insist—even to this day—that all consumption tax revenue is used to fund social security. By taking advantage of the slush fund-style accounting, they can simply say, “We can’t provide the details, but it’s all being allocated to social security,” and since the public has no way to verify the truth, the claim goes unchallenged.

It’s also convenient for them that the total amount of consumption tax revenue doesn’t actually reach the total cost of social security. The Ministry of Finance refers to the gap between the two as the “sukima” (gap). In the initial budget for fiscal year 2024, consumption tax revenue was 25 trillion yen, while social security expenses were 38 trillion yen, resulting in a gap of 13 trillion yen. Since consumption tax revenue falls far short of social security costs, it becomes easier to justify the claim that it’s being fully allocated.

There Is No Justifiable Reason to Treat the Consumption Tax as a Sacred Cow

From this perspective, some might argue that “Ultimately, if consumption tax revenue decreases, social security spending will likely decrease too, so whether it is fully allocated or not isn’t a major issue.” Indeed, social security spending might decline if consumption tax revenue falls—but the same applies equally to other tax revenues such as income tax and corporate tax. There is no reason to treat consumption tax as a sacred cow alone.

Considering the domestic economy, where real wages have been declining year-on-year amid rising prices, it is appropriate to consider consumption tax cuts as economic stimulus, as has been done in Europe so far. Compared to the cash payments favored by the Liberal Democratic Party’s platform—which tend to be saved—a zero percent tax rate on food alone would have a greater economic effect. This is because the benefit of reducing the consumption tax only reaches people if they actually spend money.

There Is Also a Risk That It Could Become an Excuse for Consumption Tax Hikes

Moreover, the misunderstanding that consumption tax is a dedicated source of social security funding causes far greater harm. If social security costs continue to rise in the future, it could easily lead to the argument that if you want to address social security expenses, you must accept consumption tax hikes.

The risk is heightened by the fact that a leading scholar, who is both a leader and theoretical pillar of fiscal austerity advocates, stated quite some time ago in a certain manuscript that the conversion of consumption tax into a social security purpose tax provides a justification for tax increases while simultaneously achieving a significant improvement in the primary fiscal balance—killing two birds with one stone.

Originally, maintaining social security should require a comprehensive review of total tax revenue, including income tax and corporate tax. It is absolutely essential to prevent the consumption tax hike from becoming an excuse.

The Conversion of Consumption Tax into a Social Security Funding Source Is Fundamentally Wrong

The very idea of using a large-scale indirect tax like the consumption tax as a funding source for social security is fundamentally mistaken. It is hard to believe that there is any fair relationship of burden and benefit between consumption tax and social security. It’s difficult to imagine any country other than Japan using individual consumption as a tax object to fund social security.

When the consumption tax was introduced in 1989, its official purpose was to correct the direct-indirect tax ratio. The direct-indirect tax ratio refers to the balance between direct taxes and indirect taxes. The goal was to lower the previously high proportion of direct taxes such as corporate and income taxes and increase the proportion of indirect taxes, mainly the consumption tax.

However, as shown in the Ministry of Finance’s chart mentioned earlier, the clear welfare purpose conversion of the consumption tax happened between 1998 and 1999. This came about because the then-ruling Liberal Democratic Party formed a coalition government with the Liberal Party, which had long advocated for converting the consumption tax into a welfare-purpose tax. In fact, from fiscal year 1999 onward, the general account budget principles explicitly stated that consumption tax revenue would be allocated to the three elderly-related expenses.

This idea was likely planted by bureaucrats from the Ministry of Finance at the time into Ichirō Ozawa, leader of the Liberal Party and a key figure in the coalition government. This nationwide falsehood began nearly 30 years ago and continues to this day.

Reporting and writing: Kenji Matsuoka

After working as a money writer, financial planner, and market analyst for a securities company, Matsuoka became independent in 1996. He writes articles on finance and asset management mainly for business and economic magazines. Author of "A Textbook for the First Year of Robo-Advisor Investing" and "A Book You Can Understand with Rich Illustrations! A book that will definitely benefit you with cashless payment. X (former Twitter)→@1847mattsuu

PHOTO: Afro