[Exclusive] Allegations Emerge Against Constitutional Democratic Party’s Naoko Shinoda for Overlooking Welfare Fraud

An email that seemed to tacitly condone the unlawful act.

Now that the ruling LDP-Komeito coalition has become a minority government in the current Diet session, one of the issues expected to become a point of contention was the introduction of an optional separate surname system for married couples. In late May, a bill was submitted by opposition parties, and deliberations have finally begun in the House of Representatives Judicial Affairs Committee.

Seeking to shake the LDP, whose members remain divided on the matter, the Constitutional Democratic Party had already thrown an early jab during a February budget subcommittee session. It came from newly elected House of Representatives member Naoko Shinoda (53, elected via Hokkaido’s proportional representation block) in the form of a question drawn from her personal experience:

“I currently use my common name, Shinoda Naoko, as a member of parliament, though my official family register name is Nakagawa. I have four children, all bearing the Nakagawa surname, while I work as Shinoda.

In this debate over the optional separate surname system, some arguments in opposition claim that children are pitiful when parents and children have different surnames. But in fact, there are already plenty of families where parents and children have different surnames. So to say such families are pitiful, I find that a completely misguided argument.”

After graduating from a public high school in eastern Hokkaido, Shinoda spent two years preparing for entrance exams before enrolling in Hokkaido University’s Faculty of Law. She passed the bar exam on her second attempt and built a legal career over two decades, focusing on supporting single-parent families and people in financial distress.

However, through those activities, and not only as a lawyer but also now as a member of parliament, evidence has emerged that raises serious doubts about her professional integrity.

In the writer’s possession are court records from a divorce trial fought between a woman, Ms. A, and her husband from 2012 to 2016. As a lawyer, Shinoda represented Ms. A (the plaintiff/petitioner) in this case, ultimately securing a Supreme Court ruling granting the divorce and awarding custody of their two children to the wife.

Moreover, the writer also obtained records of a separate lawsuit filed by the husband against Shinoda, then a practicing lawyer, seeking damages and other relief.

“A part of these records includes email exchanges between Ms. A and Shinoda while preparing for trial. Within those messages was a mail from Shinoda that appeared to tacitly condone Ms. A’s unlawful act,” revealed a source within the legal community.

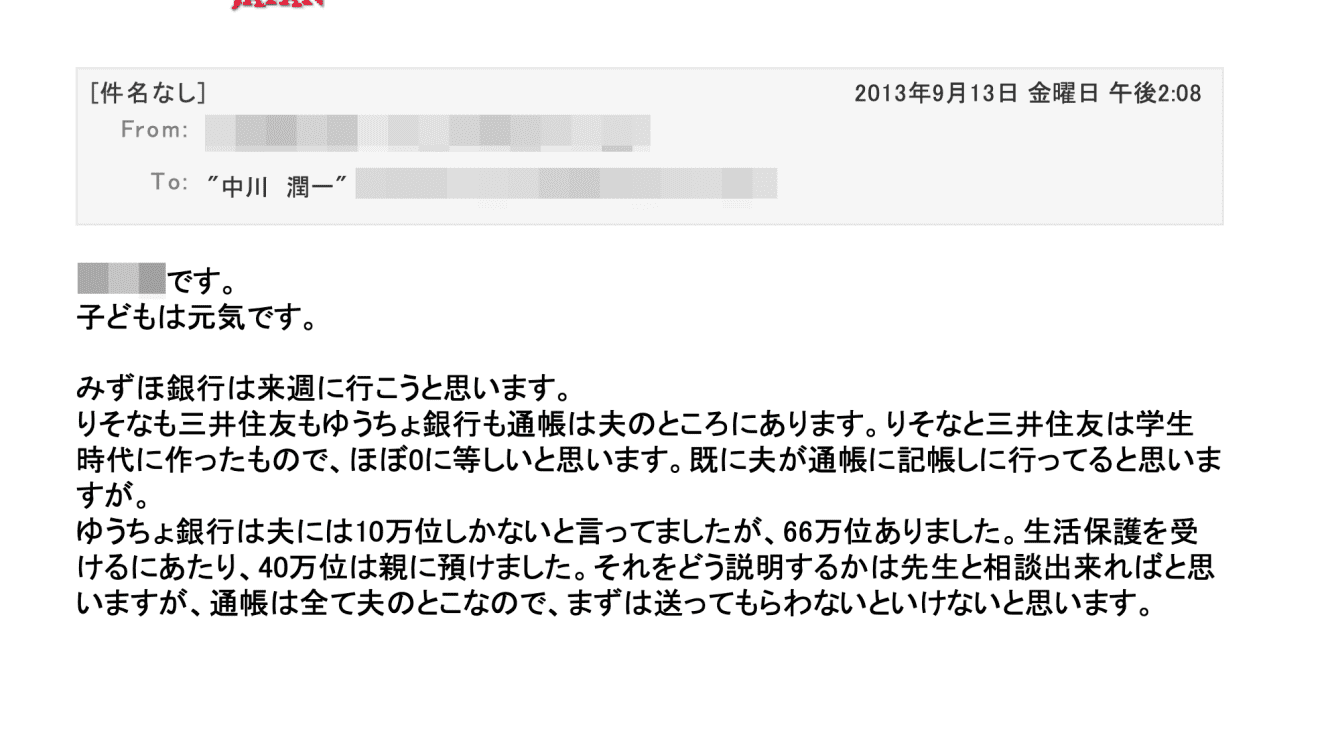

An email that Ms. A had sent to lawyer Nakagawa

The first of these emails was sent on September 13, 2013, at 11:15 a.m. from lawyer Junichi Nakagawa to Ms. A. This Nakagawa was in fact the husband of Ms. Shinoda. The two of them operated a law office together in Kushiro City, Hokkaido, and jointly represented Ms. A in her divorce proceedings. Shinoda’s email address was listed in the CC field, allowing her to receive and view the same message content.

“This is lawyer Nakagawa. (omitted)

Shinoda is currently away on a business trip, so I’m emailing in her place.

At yesterday’s court hearing, both parties submitted their documents and evidence. (omitted)

Regarding the division of property, it was agreed that both sides would disclose all of their joint bank accounts. (remainder omitted)” (original text as is)

The division of property is one of the basic matters to be settled in a divorce. It seems they agreed to disclose all accounts created during the marriage and get a full picture of the total assets.

Later that same day at 2:08 p.m., Ms. A replied directly to lawyer Nakagawa with the following:

“(omitted) Regarding the Japan Post Bank account, my husband was told there was about 100,000 yen in it, but in reality, there was about 660,000 yen. Before applying for welfare, I deposited about 400,000 yen with my parents. I’d like to consult with you on how to explain this. But since all the passbooks are with my husband, I think we need to have them sent first.” (parentheses by the writer)

From this email, what can be inferred is a suspicion that Ms. A was deliberately lowering her apparent savings balance to fraudulently receive welfare benefits.

At the time, a staff member from the regional welfare division in Kushiro Town, Hokkaido — where Ms. A lived — explained in an interview with this writer:

“As for the financial situation of welfare applicants, it’s generally limited to those with no income, no savings or cash on hand, and no foreseeable support from family. It varies by household, but for a single mother with two children, for example, about 180,000 yen a month would be considered the minimum necessary for living expenses. If savings are around 100,000 yen, they could be eligible for welfare.”

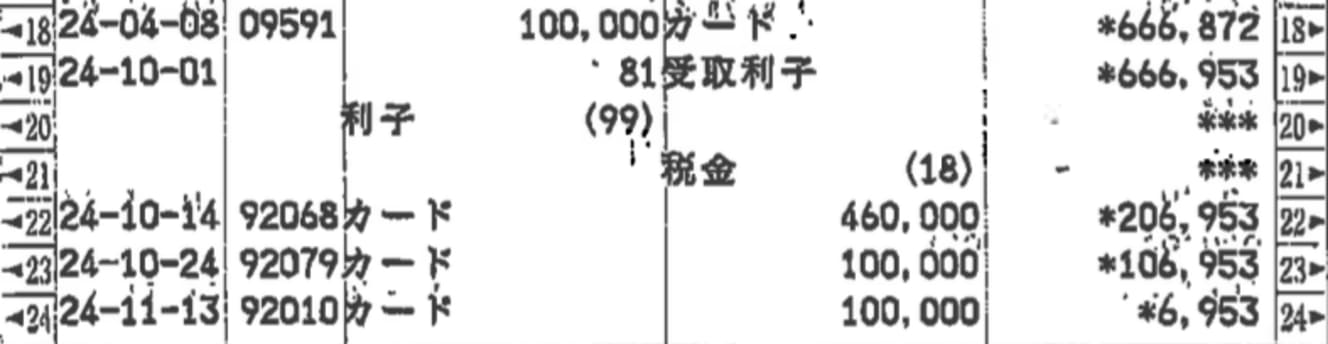

Among the court records was also a photocopy of the passbook, confirming the withdrawals as Ms. A described in her email. It appeared she had reduced her account balance to a level qualifying for welfare assistance.

However, in the property division discussions, there arose a need to show the past passbooks to the husband’s side. The passbooks recorded dates and amounts of deposits and withdrawals, and there was now a real risk that her husband — with whom she was in a fierce dispute over divorce and child custody — would discover the irregularities.

In fact, an email Ms. A sent to lawyer Nakagawa at 4:22 p.m. that same day revealed her growing anxiety:

“I had the Japan Post Bank passbook made unusable, but I did that too late, so there’s a chance (my husband has already seen the transaction history).” (parentheses by the writer)

These email exchanges strongly suggest a confession of welfare fraud. And what’s critical is how Shinoda, the lawyer (now a member of parliament), responded after receiving this kind of admission from her client.

Ordinarily, the proper course would have been to immediately correct Ms. A’s conduct and have her cease receiving welfare benefits. Yet judging by the circumstances, it appears Shinoda did not take such action.

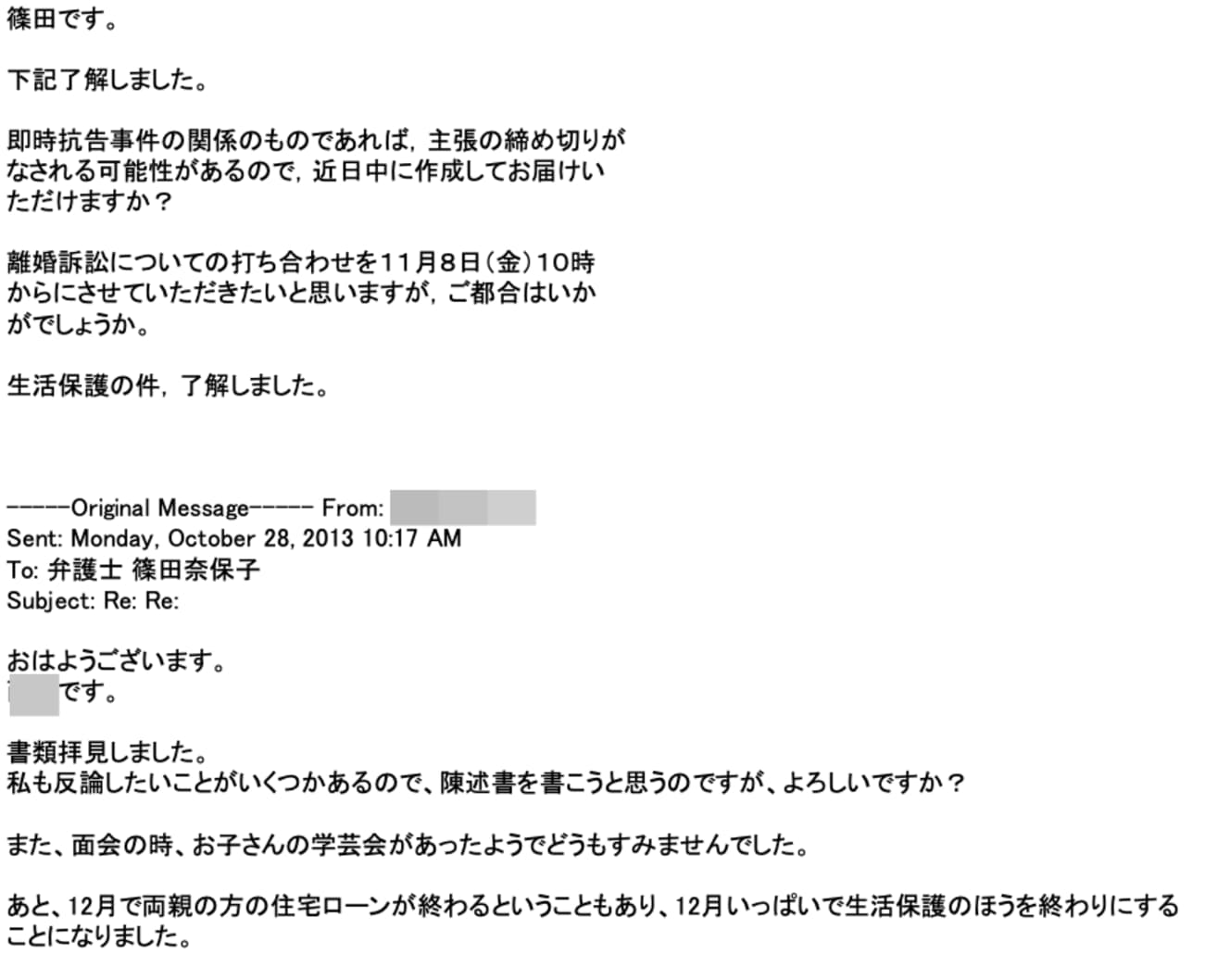

Understood regarding the welfare matter

At 10:17 a.m. on October 28, a little over a month later, Ms. A sent the following email to Ms. Shinoda:

“Good morning. (omitted) Since my parents’ mortgage will be paid off in December, I’ve decided to end my welfare assistance at the end of December.”

In response, Ms. Shinoda replied:

“This is Shinoda. (omitted) Understood regarding the welfare matter.”

The email was a report from Ms. A to Ms. Shinoda about ending her welfare assistance. However, seen from another perspective, it suggests that Shinoda had tacitly agreed to Ms. A receiving welfare for a certain period. Taken together with the content of the earlier emails, it indicates that Shinoda may have knowingly tolerated Ms. A’s fraudulent welfare claims for about four months, from September to December 2013.

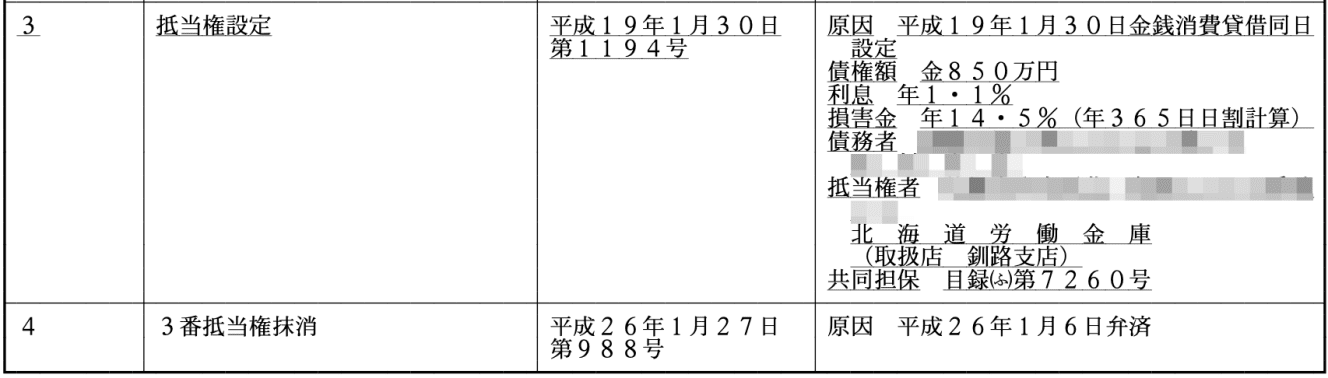

In addition to this series of email exchanges, there is other evidence supporting the claim of welfare fraud by Ms. A. A property registry for Ms. A’s family home shows the “parents’ mortgage” she mentioned in her email did in fact exist.

According to the registry, a mortgage was established on January 30, 2007, with a loan of 8.5 million yen from a financial institution under what appears to be her father’s name. The mortgage was fully repaid on January 6, 2014. This aligns closely with the details in Ms. A’s email, suggesting a high likelihood that the welfare funds she fraudulently received were used to help pay off the family’s mortgage.

And it would not be surprising if Ms. Shinoda was aware of this as well.

Though this happened over a decade ago, if Ms. Shinoda was aware of such unlawful conduct by her client, it would be highly inappropriate for her not only as a lawyer, but also as a member of parliament, to continue in her duties.

When asked for comment, Shinoda’s office replied:

“Due to attorney-client confidentiality, we will not provide any response regarding specific cases.”

While it’s understandable that she must observe professional ethics as a lawyer, as a member of parliament, she also bears a duty to provide accountability to the public — yet there was no mention of that responsibility.

Naoyuki Miyashita (nonfiction writer)

naoyukimiyashita@pm.me

Interview and text by Naoyuki Miyashita (nonfiction): Naoyuki Miyashita (Nonfiction writer)