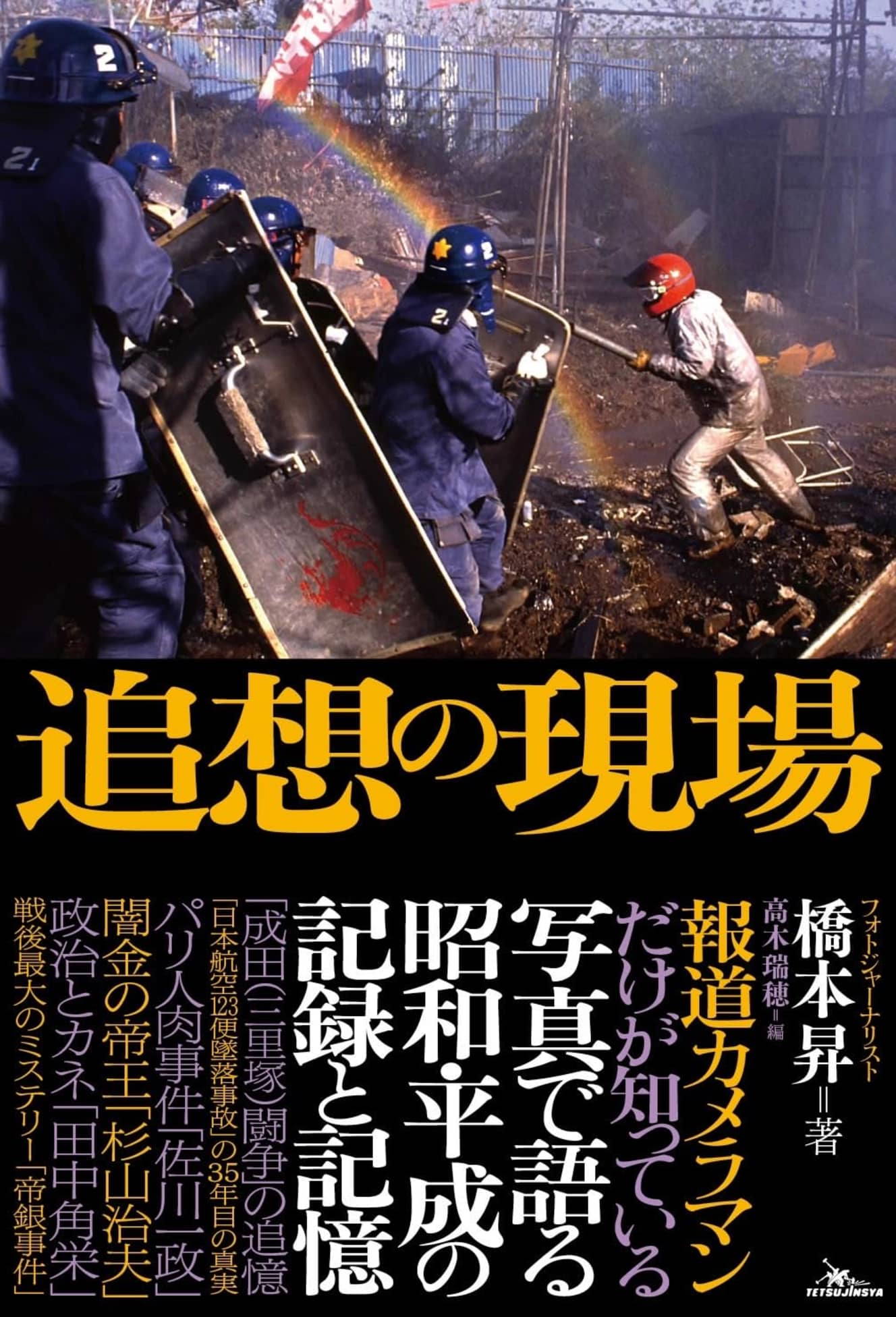

Photographer Who Witnessed Numerous Deaths in Global Conflict Zones Reflects on Japan Airlines Flight 123 Crash Site

Noboru Hashimoto, "The Scene of Reminiscence

A gruesome scene with dismembered bodies scattered around.

“When I was gathering the dismembered bodies into a blanket, I noticed that only the toes were slightly sticking out. I thought it must be a young woman, and her toenails were painted with dark pearl pink polish.

At that moment, light shone on her, and it seemed as if she was vividly illuminated in the monochrome scene. It felt like she was speaking to me, saying, ‘I didn’t want to die yet. Give me back my life.’”

This is a scene described by Sho Hashimoto (73), a veteran news photographer who has covered conflicts, accidents, and people around the world, including in war zones. He talks about the crash of Japan Airlines Flight 123 on August 12, 1985, which caused the world’s deadliest aviation accident with 520 victims.

Hashimoto, who has photographed countless significant events, has now published “Remembrance of the Scene” (Tetsujinsha), a book that showcases photographs taken over his nearly 50-year career, focusing particularly on domestic subjects. It includes coverage of incidents like the JAL crash, the collision between the submarine Nadeshio and the fishing boat Daiichi Fujimaru, and natural disasters such as the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and the Great East Japan Earthquake. Hashimoto also captures portraits of figures such as loan shark kingpin Osamu Sugiyama, self-proclaimed fascist and richest man in the world Ryoichi Sasakawa, and Issei Sagawa, involved in the Paris cannibal incident.

Each story in the book highlights moments frozen in time, showing real-life interpretations of well-known media-covered events. In an interview, Hashimoto revealed that the most memorable event for him was the JAL crash, which he covered extensively.

“The jet engine, exposed and huge, was lying at the bottom of the valley. It was a surreal and strange sight. When I touched it, it was cold and rough. As I pushed through the bamboo and climbed up, dismembered bodies and jet parts were scattered all around. The left wing of the jumbo jet, with JAL painted on it, lay nearby. Kerosene from the fuel was burning, and there was a constant hissing sound as it smoldered everywhere. The smell of burning flesh and chemicals mixed with toxic gases.”

He then captured the aforementioned scene.

“Given the situation, I wondered whether it was appropriate to photograph so many dismembered bodies and show them to the readers. So I focused on one particular aspect of the situation.”

The Reason I Chose Not to Photograph the Bodies

“Is it really about showing reality as it is?”

“Surrounded by bodies, I tried to express that in a way that wasn’t just about the bodies. Up until then, I had covered Cambodia, where I saw the Khmer Rouge being chased by the Vietnamese army and dying. Later, in Rwanda, I saw countless bodies of those massacred. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, I was in Sarajevo when a shell hit the market, killing 68 civilians in an instant. There too, bodies were scattered. The blast waves crawl along the ground, and most people lose their legs. They die, but some try to stand up with their severed limbs, and for a brief moment, our eyes met… I had those kinds of experiences.”

“Even so, the reason why the Japan Airlines crash left the deepest impression on me is that, compared to other conflict zones, the scene on Mt. Osutaka was beyond anything. There was also the feeling of regret and sadness, because there wasn’t supposed to be death there in the first place.”

“The proximity to death is fundamentally different between conflict zones and accidents. In Sarajevo at that time, civilians were always targeted by snipers, and shelling wasn’t uncommon.”

“In conflict zones, photos of bodies serve to emphasize the absurdity of war. But Mt. Osutaka is different. What’s the point of piling up body shots in such a way? One must not violate dignity.”

“The editor asked me, ‘Why are there no photos of the bodies!’ and I argued, ‘With a jumbo jet loaded with fuel crashing, readers can imagine what’s happening!’

There were media outlets that published body photos without restraint, and that was the trend at the time. But that’s just a difference in approach.”

“What do I focus on when taking photos?”

“Before entering the scene, I always create a photo story in my mind. Of course, when I enter the scene, it never turns out exactly as I imagined, so I continuously revise the photo story. That’s how I work. If I just shot randomly without a story, I wouldn’t be able to organize my thoughts.”

“I always thought about the impact and meaning my photos would have on the readers and society when published in the media. It’s not about just taking pictures of anything. I don’t just shoot as many frames as I can. If I did that, the editor might end up using them incorrectly later.”

The King of Loan Sharks who had bloodshot eyes despite his smile

It may sound cliché to simply call it artistic identity, but there is a sense of pride as an expressionist behind it. When he was young, he used to take railroad photos with a toy-like camera, being one of the original railway enthusiasts. As he grew older, he saw the photographs of the cameraman Koichi Sawada, who tragically lost his life at a young age in the conflict zone of Cambodia, and thought, “That’s so cool.” So what exactly is the motivation behind taking photos?

“It’s the interest in the subject, right? For example, Ryoichi Sasagawa. Everyone knows he’s a powerful figure in the right-wing. When I actually met him, his very presence was ‘the Don.’ I had this mischievous impulse toward the ‘Don’ Sasagawa.

There was an event where a pilot wearing a jet suit was flying in the air, and I asked him, ‘Could you wear this?’ Even though his aides were trying to stop me, he agreed. Turns out, he’s quite a humorous person. Wealthy people don’t fight. The reasons for fighting are probably something else.”

When it comes to creating images, there’s also a photograph where he buried the charismatic loan shark Haruo Sugiyama in a thousand-yen bill. In the late bubble era, people who could no longer borrow from consumer finance companies started turning to loan sharks, and their exorbitant interest rates and harsh collection methods became a social issue. That photograph embodied the very essence of money worship.

“I thought the image would be interesting, so I asked Sugiyama beforehand. He was totally up for it. When I told him, ‘Prepare two hundred million yen,’ he brought it from the bank. We unwrapped the bundles together and scattered the bills.

He posed with a smile, but his eyes were bloodshot, and he wasn’t really smiling. He exuded a harsh aura.

He grew up in extreme poverty, dropped out of middle school, and used to bite into muddy radishes straight from the fields. With that kind of background, money was the only way to rise. Money, money, money. So when someone couldn’t pay back their debt, he’d say, ‘Go to the Philippines and sell your kidney!’

It’s surprising that Sugiyama would cooperate with such an image creation. He must understand what the photo symbolizes.”

“Sugiyama didn’t mind being buried in money, which is something most people would never do. He probably doesn’t even have that sense. If he did, he wouldn’t be involved in loan sharking. The common sense of people in the loan shark business is different from ours. Reflecting on that, I think, ‘What are people really?’ It becomes the ultimate point of interest. Watching different ways of living and dying, my curiosity beats strong.”

In recent years, Hashimoto has continued not only his photography but also his writing. He now regularly publishes two handwritten articles per month on the web media “JBpress.”

“I still think of myself as a photographer who expresses everything through photos. But I believe readers are also interested in the stories behind the photos. I feel it’s my duty to pass on what I’ve seen to the next generation. The method of expression is just different.”

Passionately explaining his future interview plans, Hashimoto intends to continue being an interviewer.

The Field of Reminiscence” (Noboru Hashimoto, Mizuho Takagi, eds., Tetsujinsha)