Exclusive Mitsubishi Group Company Accused of Subcontractor Bullying After TSE Listing

“Don’t talk to anyone else about this.”

The phone rang on the morning of March 19, just after 8 a.m., as a man (hereafter referred to as A) was getting ready to go to work. The screen displayed the name of Shingo Nishinami, who was then a director at the machinery conglomerate “Tokyo Sangyo” (headquartered in Chiyoda, Tokyo). A had known Nishinami for about 10 years.

“Are you in Tokyo?”

In response to Director Nishinami’s question, A-san replied, “Yes, I am.” Director Nishinami then asked immediately:

“Is it okay if I bring the president and others and come over?”

Without allowing A to respond, Nishinami’s words were clear, and A agreed, “Yes.” It was now obvious that Tokyo Sangyo’s executives were about to visit the office of B Corporation, the construction company A headed. The purpose of the visit had already been discussed the day before, regarding a construction project involving Tokyo Sangyo.

In February of this year, B Corporation entered into a contract with Tokyo Sangyo to build a solar power plant in Nishigo Village, southern Fukushima Prefecture. Tokyo Sangyo was the main contractor for the project, and B Corporation was hired as the first-tier subcontractor.

While B Corporation is a small business with a capital of approximately 500 million yen, Tokyo Sangyo, a prestigious company within the Mitsubishi Group, is a major corporation with a capital of about 3.4 billion yen and is listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Prime Market. Therefore, it was unusual for such executives from a large corporation to visit B Corporation’s office, located in a small office building in Tokyo.

About two hours later, A welcomed the visit of Tokyo Sangyo’s president, Minoru Kambara, former president and current advisor Toshio Satomi, and Nishinami. As expected, the topic of discussion was the solar power plant project in Nishigo Village. During the meeting, President Kambara bowed and said the following:

“We will pay 850 million yen for B Corporation’s profit, including the consumption tax (a total of 935 million yen), separately. However, it is impossible to make the payment by the end of March. Please wait until after the shareholders’ meeting in June.”

Due to financial difficulties, Tokyo Sangyo requested a delay in the payment of B Corporation’s profit portion of the construction payment. President Kambara further explained the future payments as follows:

“The payment for B Corporation’s profit portion will be redirected to another project. So, please make sure to prepare such projects so we can suggest them.”

In addition to the solar power project, if there were any other construction projects B Corporation was involved in, Tokyo Sangyo suggested that the profit from those projects could be used to cover the payments. Finally, President Kamihara made a clear remark:

“All future discussions should go through Nishinami, and don’t talk to anyone else from Tokyo Sangyo.”

As of December 10, the construction payment for the solar power plant has not been fully paid, with some parts still outstanding. A shared his thoughts:

“After the promised shareholders’ meeting, I have contacted Tokyo Sangyo several times to request a meeting with President Kamihara, but it has not been realized. In fact, Tokyo Sangyo holds a 9.2% stake in our company and we have a deep relationship. I even have a desk at their office. Because of this, I used to be able to meet the president without an appointment, but now I am turned away with the response, ‘You can’t meet if you just show up.’

I feel like I’ve run away from the payment. Due to the delay in payments from Tokyo Sangyo, the number of people at my company, which was once around 100, has now decreased to 30. Many of them left because they lost faith in our company’s financial situation.”

Tokyo Sangyo’s Forbidden Move

Why was Company B pushed into such a difficult position? To understand this, we need to look back at the circumstances that led to the construction contract for the solar power plant with Tokyo Sangyo.

First, the solar power plants in Nishigo Village were planted as two adjacent plants. Company B was involved only in the construction of the second plant (hereinafter referred to as the second plant).

The client for both plants was Shanghai Electric Power Japan, and the general contractor was Tokyo Sangyo. Initially, a construction-related company that was the first-tier subcontractor for the first plant (hereinafter referred to as the first plant) continued to undertake the construction of the second plant.

“When the first plant’s construction was completed and they moved on to the second plant, the first-tier subcontractor ran into a funding shortfall. It is said that this was due to additional construction work worth several billion yen. Despite this, Tokyo Sangyo decided to continue the project and advanced about 6.5 billion yen from the second plant’s budget to this first-tier subcontractor. However, even with this, the project couldn’t continue, and the first-tier subcontractor eventually had to withdraw.” (Construction industry insider)

In other words, there was a possibility that the second plant’s construction was set to proceed without securing sufficient budget.

Afterward, the first-tier subcontractor officially withdrew in September 2023. It was in the following October that A received a phone call from Advisor Satomi, saying, “There’s a complicated issue here, A-kun. Could you help us out?”

“As mentioned earlier, Tokyo Industries not only holds some of our company’s shares but has also provided us with financial support. As a contractor, it’s not ideal to take over a project halfway through, especially when another company has already started it, because it’s unclear to what extent we might be legally responsible for any defects. Some people within the company also opposed it, saying ‘The risks are too high,’ but considering the history of support we’ve received and the trust we’ve built through our dealings, I decided to take it on.” (A)

However, during the process of entering into the construction contract, B company encountered a prohibited practice known as price-fixing orders, where the main contractor uses their position to effectively dictate the contract price.

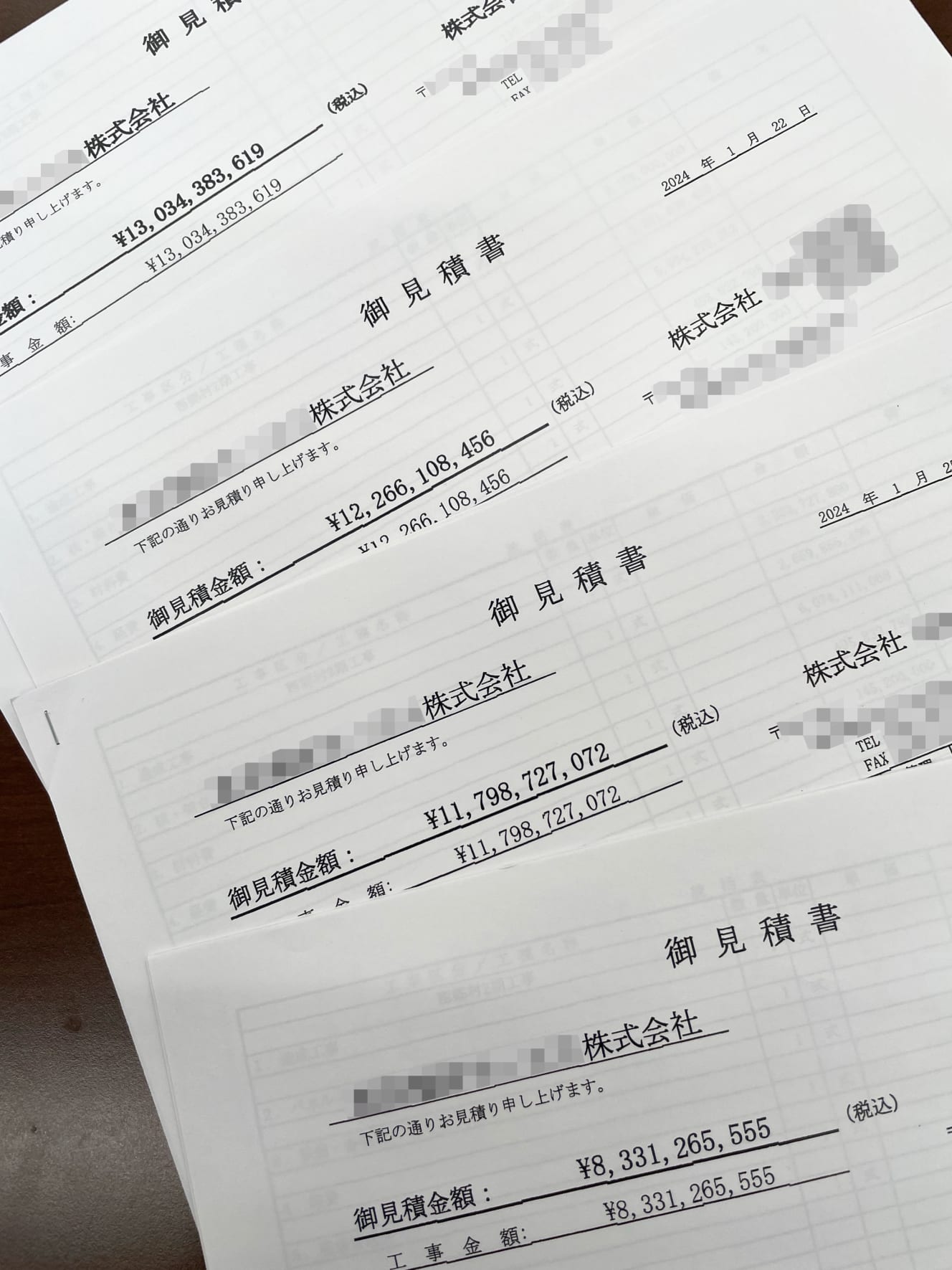

In November 2023, B company first sent employees to check the progress of the second plant construction in Saigo Village. Based on their findings, they estimated the contract price to be approximately 13 billion yen and submitted the estimate. However, they were reportedly told by N, the head of Tokyo Industry’s renewable energy division, the following:

“They said, ‘The Saigo Village solar power plant is a losing project, so can you make the payment by outsourcing the profit and then settle it with additional work later?'”

There was pressure to reduce the contract amount by excluding B Company’s profit from the estimate. A said.

“A series of discussions were held with Director N, and Tokyo Industry suggested cost-saving measures, such as supplying some of the materials. As a result, we revised the estimate to approximately 11.7 billion yen. However, at that point, we requested that about 10-15% of the contract amount be paid in advance as our profit.”

‘s internal approval process failed to go through.

However, another problem arises. It becomes clear that the cables needed for the construction of the solar power plant, specifically the transmission cables, cannot be secured as planned.

Upon inquiring with relevant parties, it was discovered that a subsidiary of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) had the required cables in stock. As a result, as a last resort, the decision was made to bring in another TEPCO subsidiary as a first-tier subcontractor to ensure the smooth procurement of the cables by restructuring the system.

“Due to this unexpected response, we ended up as a second-tier subcontractor. Furthermore, Tokyo Industry refused to make the advance payment of our requested profit and decided to directly pay the four third-tier subcontractors, which were our subcontractors. This decision was based on their previous experience of prepaying funds to the first-tier subcontractor of the first plant construction, only for the project to stall in the end. It was an unreasonable treatment, assuming that we, who had no involvement with the first plant, would face the same risks.” (According to Tokyo Industry, “It is true that we directly paid the construction fees to the third-tier subcontractors. The reason for this is that B Company was facing financial uncertainty, and the third-tier subcontractors made a request. B Company also agreed to this.”)

N Department Head reportedly said, “We’ve already made significant payments to the original first-tier subcontractor, so there’s no budget left,” and “This is the only way the internal approval process will go through.” (Tokyo Industry responded to N Department Head’s statements saying, “There is no truth to these remarks.”)

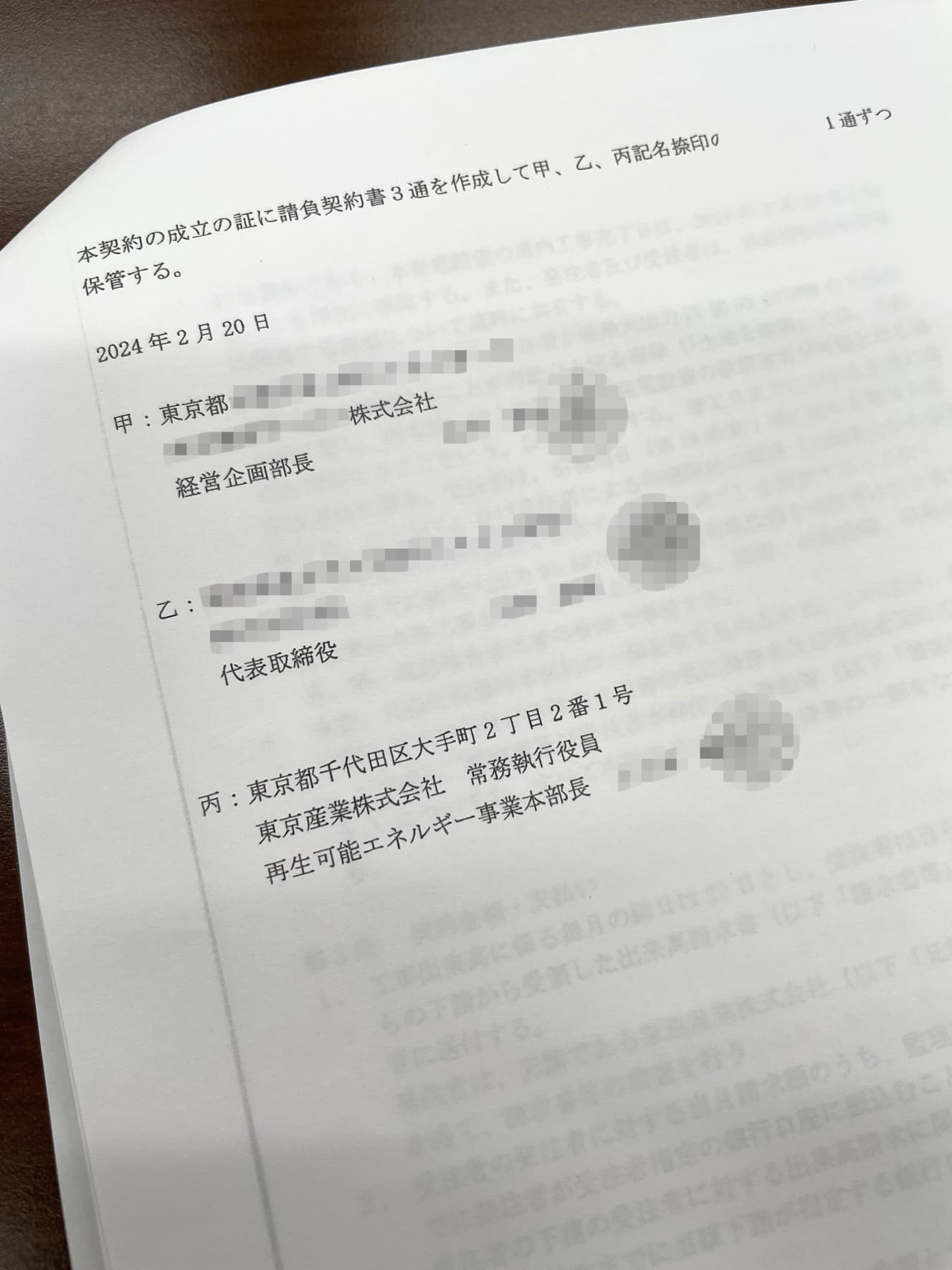

The estimate submitted later was 8.3 billion yen. Finally, on February 20, 2024, B Company signed the “Solar Power Facility Construction Contract” with Tokyo Industry and the subsidiary company, with the amount being reduced to 7.9 billion yen.

“This amount does not include our profit; it is only the cost required for the construction of the solar power plant. Even after signing the contract with Tokyo Industry, we continued to discuss the payment method for our profit portion.” (Same source)

However, the discussions did not lead to a resolution, and eventually, the situation escalated to the earlier mentioned scene. At Tokyo Industry, the payment for the profit portion that B Company should have received remained unresolved, and President Kamihara intervened, requesting a delay in payment.

Regarding this series of exchanges, Yujiro Ohno, the director of the Tokyo office at the administrative scrivener corporation Meinan Keiei, which provides legal compliance advice to construction companies, pointed out the following.

“The practice of a contractor unilaterally setting the contract price and entering into a contract is referred to as ‘shikiri-hattyo’ (price-fixing orders). This is considered an improper use of the contractor’s position as a main contractor and may violate Article 19-3 of the Construction Industry Act, which prohibits unreasonably low contract prices below the usual recognized costs.

However, in this case, since a contract was signed, it could be interpreted that there was mutual agreement between the parties. Even so, regarding the fairness of the contract price, it would not be unusual for the supervising authority, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, to request action from the Fair Trade Commission through a measures request or similar actions in this situation.”

“Shut up. No unnecessary talk.”

How will the management of Tokyo Sangyo respond?

On the evening of December 5, after finishing a dinner meeting, President Kamihara of Tokyo Sangyo was approached by a reporter as he got into his chauffeur-driven black sedan.

――About the solar power plant in Saigo-mura.

Kamihara: “Ah, sorry. That has nothing to do with me at all.”

――B Company, which was involved in the second-phase construction

Kamihara: “Shut up. No unnecessary talk. Sorry, but today, I’m in a different position.”

――You’re the president of Tokyo Sangyo, right?

Kamihara: “Yes, that’s right.”

――B Company submitted an estimate of 13 billion yen, but it was eventually reduced to 7.9 billion yen.

Kamihara: “I don’t understand any of that.”

――Doesn’t this possibly violate the Construction Industry Law?

Kamihara (irritated tone): “What?”

――The possibility of violating the Construction Industry Law.

Kamihara: “Please go through the general affairs department for these kinds of inquiries. Yes, please.”

――I’d like to clarify the facts here.

Kamihara: “No, don’t come at this time. Honestly, it’s rude.”

――If we go through the company, will you accept an interview?

Kamihara: “Yes, I’ll do it. Please come during the day. I absolutely hate ambush-type interviews. We’ll talk in the proper setting.”

With that, Kamihara rushed into his home. The next morning, when the reporter requested an interview with Tokyo Sangyo, the head of the General Affairs and Human Resources department, Mr. T, responded:

Mr. T: “I’ve heard from Kamihara, but I’ll be handling this from the general affairs side. Our company doesn’t recognize that we made any unfair contracts, so I don’t think there’s anything to discuss.”

Let’s work together and move forward.

On the other hand, there were individuals who revealed the following facts. Below is a conversation with Director Nishinami over the phone.

―― On March 19, Nishinami-san and President Kamihara visited B’s office. During that time, President Kamihara mentioned that B’s profit portion would be allocated to another project for payment.

“At that time, I think it was not about allocation, but rather, the conversation was about cooperating again on a different job, to work together. I don’t really understand whether the contract terms were unfair or not. He (A-san) said he was in a lot of trouble, so we were just talking about how to help him, that’s all.”

―― If the 7.9 billion yen contract is the correct amount, why did you consider helping B?

“Well, it was the correct amount, that’s for sure. But, I’m not in a position to talk about this, so can you please contact the General Affairs Department?”

―― If 7.9 billion yen is the correct amount, why did you have to arrange a new project for B?

“Well, I’m sorry, but I think when conducting interviews, it’s better to go through the proper channels, so I’d prefer you to do that.”

When a formal written inquiry was sent to Tokyo Industry, they provided the following response:

“The reduction in the estimate was due to adjustments for costs we paid and costs we directly ordered during the period leading up to the contract. We did not request B to enter into the contract at an unreasonably low amount, and B agreed to the contract. We believe that this does not violate construction industry laws.

It is true that on March 19, President Kamihara and two others visited B’s office, but there is no truth to the statement that Kamihara made those remarks.”

On September 29, B signed an agreement with Tokyo Industry. The agreement specifies that the construction work for the West Village solar power plant will be taken over by a Tokyo Industry affiliate on behalf of B.

“The construction contract was terminated, and as a result, the project was transferred to Tokyo Industry’s subsidiary,” said A-san.

Then, a settlement amount was paid, but it amounted to just over 10 million yen, which was far less than the 93.5 million yen originally requested.

Interview and text by Naoyuki Miyashita

naoyukimiyashita@pm.me

Interview and text by: Naoyuki Miyashita (nonfiction writer)