Only 150 forensic anatomists in Japan… A close look at the work of forensic anatomists who face death

Only 150 forensic anatomists in Japan stand on their feet for more than four hours, fight the smell of decay, and identify the cause of death as well as unidentified bodies.

Have you ever heard of the job of a forensic autopsy doctor, which involves dealing with death on a daily basis? They dissect various corpses, including those brought in one after another by investigative agencies, and are specialists in determining the cause of death. This time, FRIDAY interviewed Dr. Takahisa Okuda, a professor of forensic medicine at Nihon University School of Medicine. We covered the forefront of forensic anatomy, which is often the subject of TV dramas, but is rarely seen in real life.

At nine o’clock in the morning in late November, a group of six people in work clothes entered Mr. Okuda’s autopsy room. They were a coroner and a forensic scientist. Inside the huge plastic “body bag” they were holding was the drowned body of a woman to be dissected.

The autopsy room had previously been filled with the smell of chlorine disinfectant, but as soon as the bag was opened, the smell of decay immediately filled the air.

A drowned corpse has gas in its stomach, so when you insert a scalpel into it, it gushes out all at once and you are hit with a strong smell.

Mr. Okuda quietly spoke to the flinching FRIDAY reporter. While the forensics team was taking pictures of the body before the autopsy, Mr. Okuda and the coroner shared information about the scene where the body was found and the medical history of the body, and exchanged opinions in a small room attached to the room.

At 9:30 a.m., he put on a plastic surgical suit and rubber gloves and went back to the autopsy room.

The equipment is almost the same as that used in surgery on a living person. The equipment is almost the same as for a live person. The only special thing is that we put an activated charcoal pack under the mask to suppress the smell of the decomposing body. The effect is only comforting, though. ……”

At 9:45 a.m., the autopsy began. From the standpoint of hygiene and anti-corona, the reporter had to wait outside the room.

It was 1:30 in the afternoon when the door to the autopsy room opened again. After submitting a brief report to the coroner, the autopsy was over. Mr. Okuda bought some rice balls at a convenience store and returned to the professor’s office for a late lunch. When a reporter asked him if he would lose the ability to eat, Okuda replied, “I can’t worry about that.

I can’t worry about that. Work is work. My private life is my private life. I’m surprisingly thick-skinned.

He laughed bitterly. The autopsy usually starts at 9:00 a.m. and goes on for about four hours without a break.

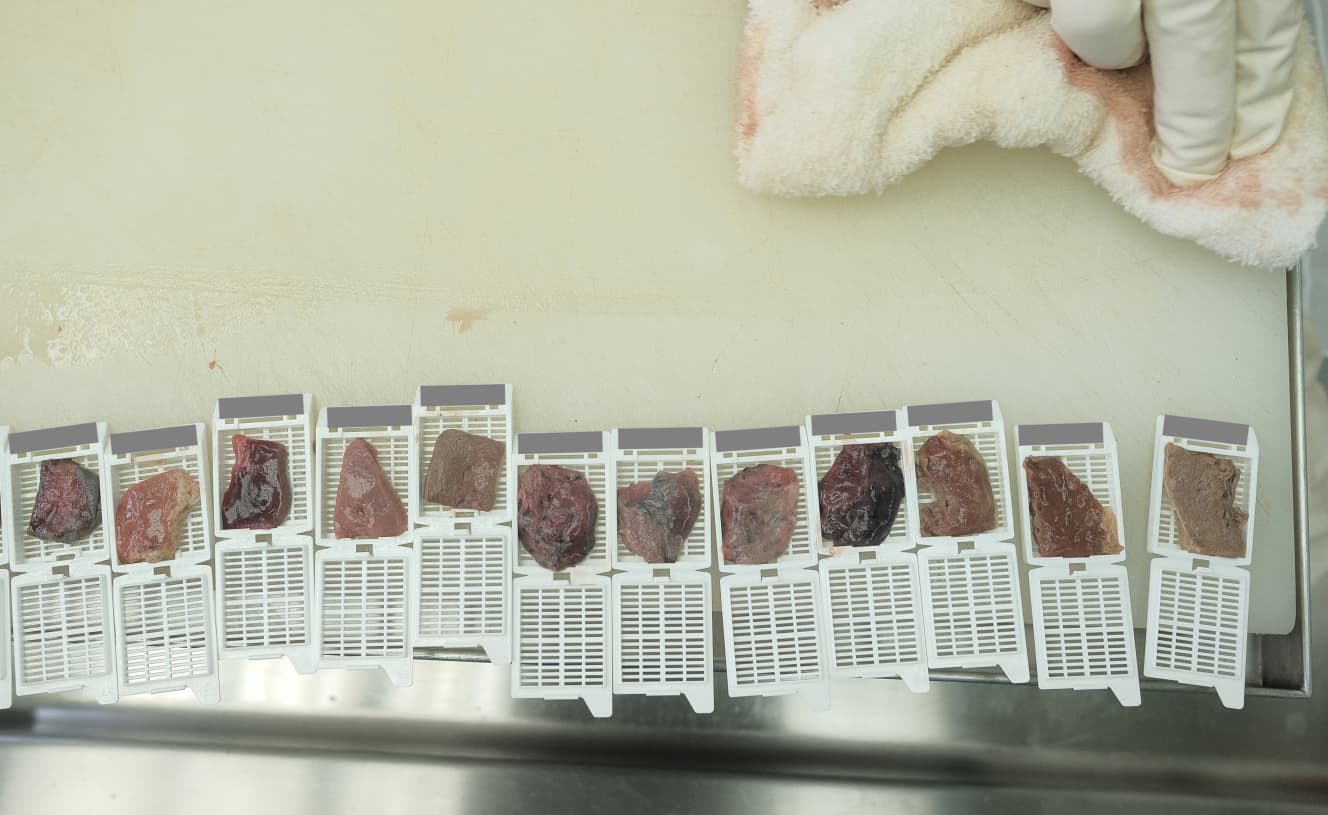

In addition to the forensics, we also take pictures of the damaged parts of the body. If the body has a lot of damage, such as from an accident, it may take about an hour and a half. After that, we take a scalpel and remove all the organs, regardless of the cause of death. Finally, the brain is removed. Then, this time, the organs themselves are scalped and probed in detail for any abnormalities. Blood is also drawn and subjected to a drug test. The whole process takes about three hours.

After the dissection is complete, all the incisions are stitched up neatly. After that, the whole body is washed for about fifteen minutes to remove the blood and dirt. Then – and this may just be me – I make sure to greet the body before and after the autopsy. Before the autopsy, I tell them, “We are about to perform an autopsy on this case,” and after the autopsy, I tell them, “This is what we found out. I think the most important thing is to be polite to the deceased.

Forensic anatomists are not only responsible for determining the cause of death. In recent years, forensic autopsies have even used the latest technology to match unidentified bodies.

We use a method called the ‘superimposing method’ to identify the body. We use CT to recreate the skeleton of the face from the skeleton of the body. Then, we can identify the person by comparing it with photographs taken before death. Even if the body is decomposed, the skeletal structure remains unchanged, so it is very useful when the identity of the person cannot be determined.

Unforgettable autopsies

Mr. Okuda dissects about 70 corpses a year. He also gives lectures at universities and prepares expert opinions on the cause of death, among other duties. There is one place that Mr. Okuda takes time out of his busy schedule to visit. It is an exorcism.

There are times when I feel that I am possessed by something. Whenever something bad happens around me, I make sure to go there. To tell you the truth, my bicycle was recently stolen (laughs). I thought it was definitely possessed by a spirit, so I’m going to the shrine again this weekend to have it exorcised.

Currently, there are only about 150 anatomists in Japan. There are currently only about 150 autopsy doctors in Japan, and only two forensic autopsy doctors at Nihon University, including Okuda. What is the reason why he is able to work for a long time in a field that is both physically and mentally demanding? When I asked Dr. Okuda, he told me about an autopsy he performed five years ago.

There was a case where a man died at home the day after he was beaten. An acquaintance of the man was suspected of murder, but when they investigated, they found a large amount of sleeping pills in the victim’s stomach. It was a suicide. Autopsies are usually performed to determine the cause of death and catch suspects, but for the first time, I was able to prevent false accusations from happening. It was my first experience to realize that some people can be saved through this work. Being able to be the last bastion of proof of innocence is the most rewarding part of this job.

With his conviction, Mr. Okuda continues to confront death. Finally, he talked about the future of forensic anatomists.

The tendency of the bodies brought to us differs depending on the era. Recently, the most common type of deaths are those of people living alone together. For example, when living with a dementia patient, the caregiver dies before the patient does. The person left behind knows that he or she is dead, but they don’t know what to do with it, so they often leave the body unattended until the smell of decomposition is noticed by others. Deaths of people living alone together are always sent to a judicial autopsy because they are judged to be cases, but the number of such cases has been increasing dramatically in recent years. I think this is a strain of our super-aging society.

My current goal is to pick up the voices of the deceased that can be heard only by forensic anatomists, and to give them back to society. If this becomes widespread, we may be able to prevent sad accidents from happening. I would like to construct a method of transmission for this purpose. As I continue to look at death, I would like to continue to look for what I can do for the living.”

For the sake of the people living in Japan, Mr. Okuda continues to face death today.

From “FRIDAY” December 24, 2021 issue

PHOTO: Soichiro Koriyama