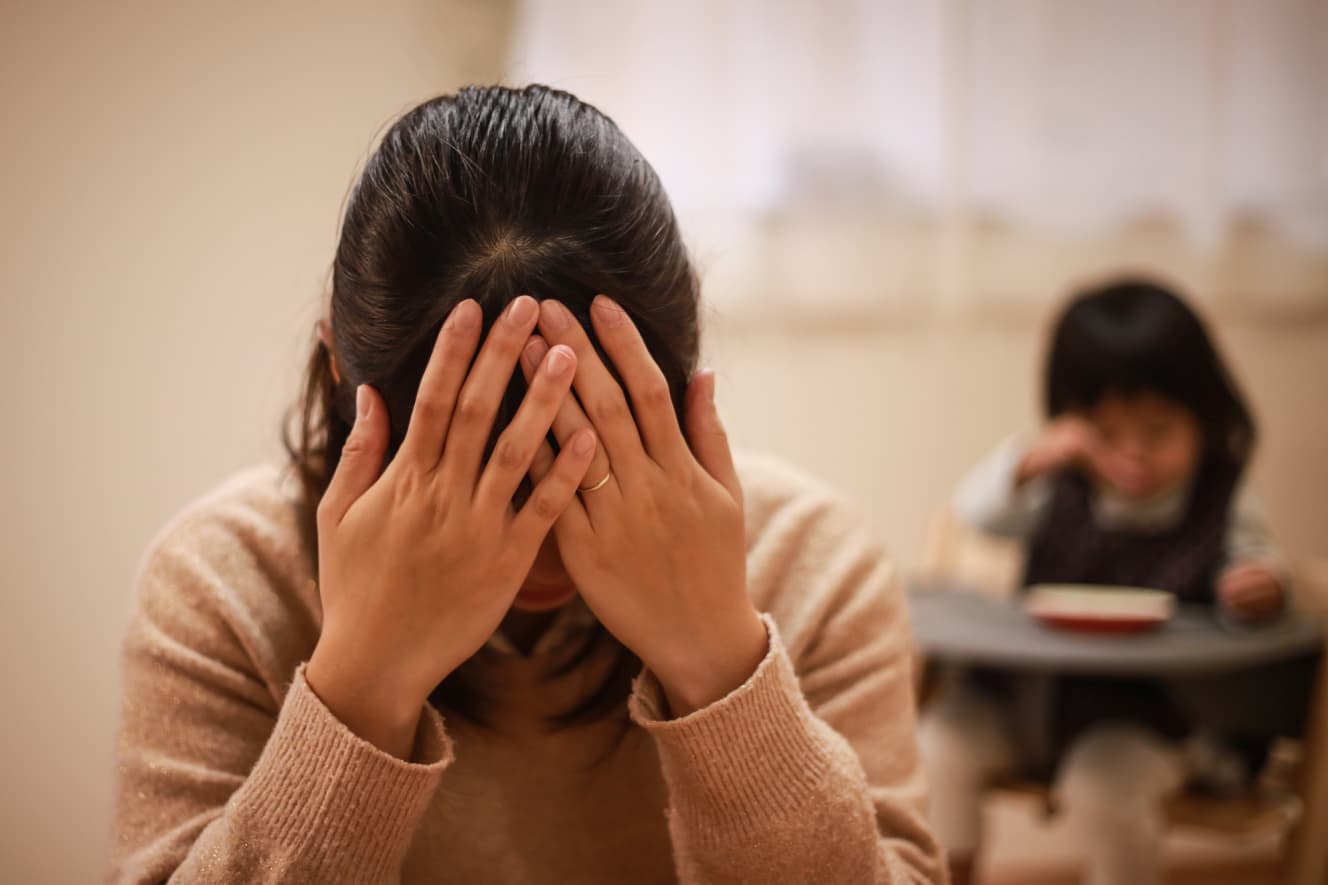

2-Year-Olds Using Smartphones for 6 Hours a Day Report on Parents Relying on App-Based Parenting and Surprising Claims of English Education Before Learning Japanese

Nonfiction writer Kouta Ishii takes a close look at the society and incidents that are looming! Shocking Reportage

Less than 1 hour 48.5%

Less than 1 to 2 hours 29.5%

Less than 2 to 4 hours 17.9%

4 hours or more 4.1%”

This is the survey result from the paper introduced in [Part 1: At Age 2, 58% of Toddlers Use the Internet and Show No Interest in Insects or Outdoor Play]. And in recent years, there has been a trend where much of parenting is done through apps.

The recent book ‘Report on How Smartphone Parenting is Ruining Children’ (Shinchosha) sheds light on the reality of smartphone parenting. We will look into the reality of parenting replaced by apps, citing this book.

Childcare teachers do not necessarily think that smartphone use is bad. Smartphones have their own benefits, but there are abilities in direct parenting by parents that can only be nurtured through direct interaction. What the teachers are concerned about is that by replacing everything with apps, these latter abilities may not develop.

‘Stop Crying App’ and the Sound of a Vacuum Cleaner

The director of a nursery school interviewed for this book says:

“A commonly used tool by recent parents is the “Stop Crying App.” Young children cry frequently. At such times, if you activate the app, sounds like a vacuum cleaner or plastic, along with various images, play. The children are attracted to these sounds and videos and stop crying immediately.

Of course, I understand that parents use it because they are troubled. However, children cry because they have something they want to express. For parents, even though it might be a bit troublesome, by soothing the child and understanding and fulfilling their wishes, an attachment relationship is formed and emotional growth occurs. But what the app does is ignore all of this and simply stop the crying mechanically. Children who are raised in this manner regularly often show differences compared to those who are not.”

‘Stop Crying Apps’ are not the only tools substituting parts of parenting. Besides the ‘Bedtime Apps’ introduced in [Part 1], there are countless others like ‘Singing Apps’ and ‘Fuss Prevention Apps.’

According to the teachers, children who interact with these apps regularly often exhibit more emotional instability compared to other children. They tend to panic over minor issues, hit other children, break things, and refuse to nap, among other behaviors.

The director says:

“When observing at the nursery, there are clear problems arising with the children. But it’s difficult to tell the parents. If an older teacher says something, they are dismissed with “Times are different from when you were teaching.” If a younger teacher says something, they are met with anger for not understanding the challenges of parenting. As a result, we end up unable to say anything and must categorize it as the child’s characteristics.”

Such parents tend to use apps not only for daily life matters but also for educational purposes.

At a certain nursery, a survey was conducted among parents, revealing that some families show their children smartphones for 5 to 6 hours a day. A parent of a 2-year-old reportedly said:

“At home, we basically let our child use the smartphone. They use it for about six hours. We let them watch their favorite videos, but as parents, we also have them use educational apps. These include puzzles and other apps that develop cognitive skills. Additionally, we also use English and math apps.”

The parents seemed convinced that exposing their child to native English and using educational apps as early as possible was beneficial.

The teacher offered this advice:

“Improving a child’s cognitive abilities is important. However, your child is only two years old and doesn’t even speak Japanese yet. What happens if the parent doesn’t speak to them in Japanese and instead has them listen to English apps for hours? Even educational apps might be better suited for a later age when the child can walk and play with other kids. What’s essential now is for the parent to interact directly, providing affection and a rich vocabulary.”

The parent responded with ‘Understood’ and left, but from the teacher’s perspective, the use of apps did not decrease; in fact, it seemed to increase. In reality, the child, even at three years old, could barely speak and struggled to interact with others.

“I Lack Confidence in Playing Well”

The teacher arranged another meeting and suggested reducing the use of apps. The parent responded:

“I lack confidence in playing well with my child. I don’t know how to do it, and I get frustrated quickly when things don’t go as planned. So I think it’s much better to leave it to the apps rather than me trying to play.”

The parent then went on and on about the impressive reviews of the pet-raising app they were currently using.

Based on this, the teacher says:

“Today’s parents are from a generation that grew up using smartphones regularly. As a result, many believe that it’s reassuring to leave things to apps. They think it’s more efficient for apps to raise their children rather than doing it themselves. They say things like ‘It’s better to use an app for lullabies’ or ‘It’s better to show videos than to teach words myself.’ With this mindset, it’s challenging for us to make them understand that there are many aspects of parenting that cannot be replaced by apps.”

While apps can be wonderful when used correctly, if the age or method of use is wrong, they could become a hindrance to development. The teacher is concerned about this aspect.

However, the number of parenting apps is increasing daily, and countless are introduced on parenting sites. For developers, it’s natural to promote these apps as more use translates to more profit. But if parents are swayed by this, the ones who suffer are the children.

The teacher says:

“Among parents, those who are particularly lacking in confidence seem to depend more on apps. Because they lack confidence, they delegate everything to apps. Once they start using them, they continue to rely on them consistently. It’s a fact that some children, even after graduating from nursery, have parents who have continued to rely on smartphones.”

The details on how children are raised are thoroughly discussed in ‘Report on How Smartphone Parenting is Ruining Children.’

What the teachers are raising alarms about is not the smartphones or apps themselves, but the fact that parents do not properly understand their appropriate use. It is not an exaggeration to say that there are almost no opportunities to teach this.

Perhaps there needs to be more detailed instruction on these issues in parenting classes or parenting programs held by municipalities and other organizations.

Interview and text: Kota Ishii

Born in Tokyo in 1977. Nonfiction writer. He has reported and written about culture, history, and medicine in Japan and abroad. His books include "Absolute Poverty," "The Body," "The House of 'Demons'," "43 Killing Intent," "Let's Talk about Real Poverty," "Social Map of Disparity and Division," and "Reporto: Who Kills the Japanese Language?