The Undiscovered Importance of CLS, a “Companion” for Children Fighting Childhood Cancer

On February 15, International Childhood Cancer Day, FRIDAY Digital published an article about Sachi Ando, who died suddenly of leukemia at the age of 9 in 2009, and her mother, Akiko Ando, who looked after her. At the time of Sachi’s battle with the COVID-19 crisis, the number of people with access to the ward was extremely limited, but the Ando family was supported by Miwa Sasaki, a Child Life Specialist (“CLS”) working in the Pediatric Internal Medicine Unit at Nagoya University Hospital.

CLSs support hospitalized children and their families.’ The effort began in the U.S. in the 20’s and is now becoming a very important post in the field of pediatric care, so much so that the American Academy of Pediatrics highly praises CLSs as an integral part of pediatric care. There are as many as 20 to 30 CLSs working at children’s hospitals in the United States.

In Japan, however, the CLS profession has a short history and is not well known, but efforts are gradually spreading. Sasaki, one of the 50 or so CLSs active in Japan, said, “We have a lot of children here who are dedicated to their treatment.

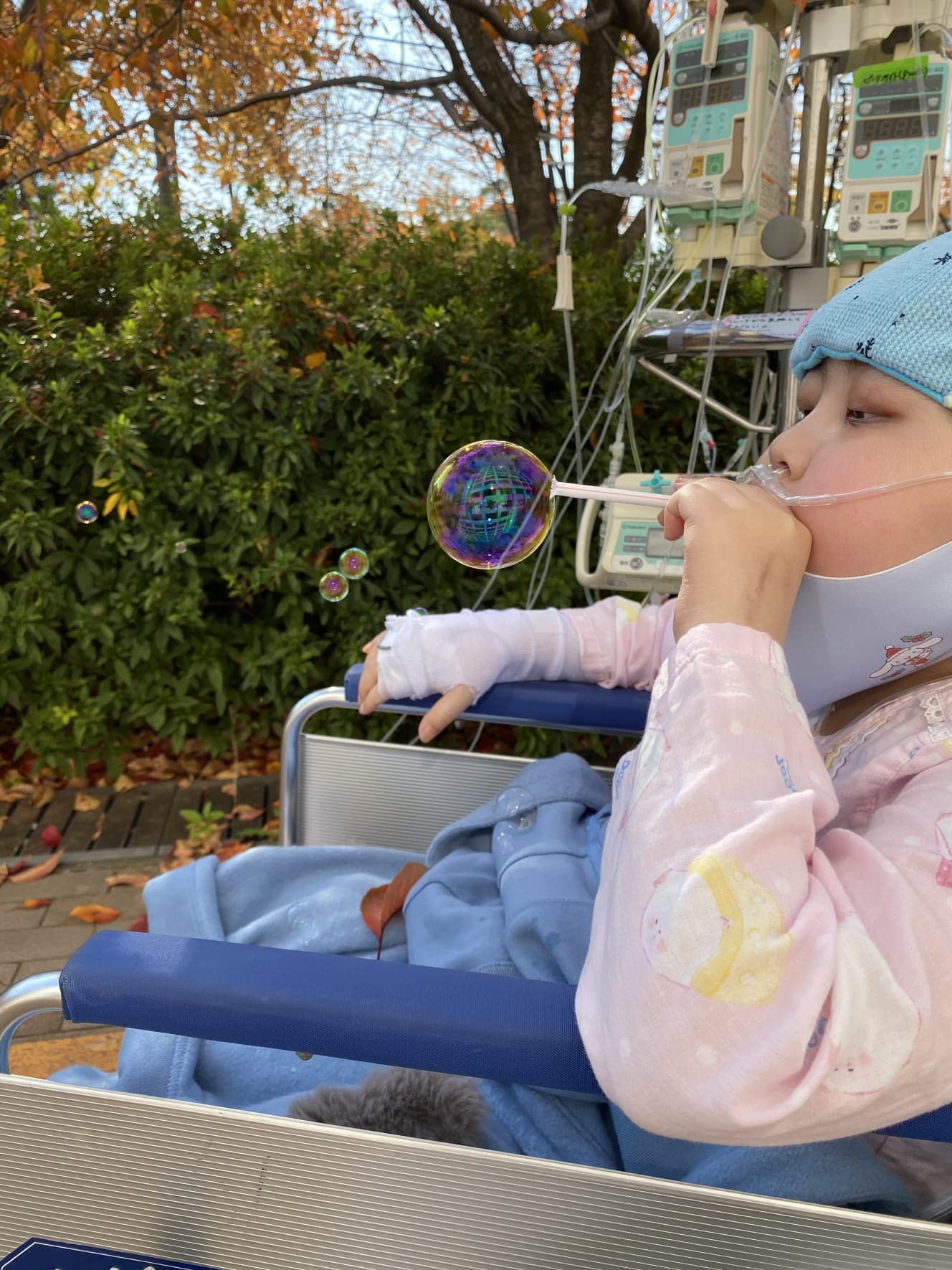

Many children stay in the hospital for six months to a year or two to focus on their treatment. In a hospital, children are limited in what they can do of their own volition, their feelings are not respected, and they may lose confidence.

What can help them recover is “play. In play, their opinions are respected. Even the act of choosing the color of origami is important. In medical care, they cannot do what they want, so I try to help them feel that their feelings are respected and that they can make their own choices in play and conversation with me.

I try to convey to them that I care about them by talking to them in various situations. I hope that making the children feel that they are cared for will make them feel secure.

This “sense of security” leads to the children’s ability to face treatment.

For example, when children go for surgery or examinations, we use dolls to simulate the experience so that they can feel at ease. By doing this, even though they don’t like it, they will take off their own clothes for the examination or hold out their hands for the injection, even though they are crying.

In addition to preparation, CLSs provide therapeutic play, emotional support during procedures and examinations, psychosocial support for families, and grief care (support when saying goodbye to a child or sibling).

In an old American document, a boy who repeatedly experienced being wrapped in a white sheet for restraint was so traumatized by the experience that he could no longer sleep in the white sheet after being discharged from the hospital.

Even in Japanese hospitals, when children’s blood is drawn, they are sometimes wrapped in towels to restrain them. A child who has had such an experience many times in the hospital may have flashbacks to it after returning home. The medical community must be aware that medical care can take a toll on a child’s mind.

Currently, it is estimated that about 2,000 to 3,000 children are affected by childhood cancer each year. Unlike in the past, about 80% of childhood cancer cases are curable, but the harsh reality still awaits some children.

Even so, there are situations in medical care where restraint is necessary, and tests and procedures are absolutely necessary. However, if the medical staff can make such considerations as ‘hold hands with the mother’ or ‘play the child’s favorite music,’ I think it will make the medical treatment a little kinder to the child. It is very important for the medical staff to be involved in the treatment from that perspective.

How did Mr. Sasaki first encounter CLS?

I was studying developmental psychology at university and wanted to work with children in the future, so I did various part-time jobs and volunteered (with children).

One of those experiences was volunteering to play with children in a playroom in a pediatric ward, and it was there that I met Ms. Akemi Fujii, a leading CLS specialist in Japan. Ms. Fujii was creating a space where people could have fun in the hospital with children who were going through difficult treatment. It was there that I learned that there was a job where I could cherish the joyful time with children facing medical treatment,” she said.

In Japan, there were no universities that offered the curriculum required for CLS certification, so Mr. Sasaki went to the U.S. to obtain his CLS certification.

It was almost 20 years ago that I studied abroad,” he said. “The first year of the program was a practicum at a daycare center, and the second year was a practicum internship at a hospital.

It was common for families to choose to adopt rather than have a child themselves if they had a child who needed a parent. Children with illnesses and disabilities also studied in the same class, and such children were not singled out, but felt as if they were the norm. It was very good to be in that kind of environment.”

After graduating from university, students are required to intern under a CLS supervisor, after which they take an exam, and if they pass the exam, they are allowed to work as a CLS.

Mr. Sasaki also engaged in an internship after college. He was then able to successfully pass the exam.

Twenty years ago, children’s rights and diversity were rarely discussed in Japan. It is likely that the experience of progressive initiatives and learning enabled Mr. Sasaki to provide high quality care in Japan.

Even today, CLS certification can only be obtained in the U.S., making CLS certification holders invaluable. The pediatric internal medicine ward at Nagoya University Hospital, where Dr. Sasaki works, has 37 beds and is always full.

It is difficult to see all the children in the hospital every day, which presents a dilemma,” he says. I try to make adjustments and go to see children who are in private rooms, newly admitted children, and children who are not doing so well, starting with those who have the greatest need to see me. It may look like I am providing support, but I really enjoy playing with the children, and more often than not, I am the one who gets the energy.

Sasaki’s face is cheerful as he speaks. His soft smile conveys his support for the children, even without seeing the actual scene.

However, CLS cannot be spent only with a smile. Although childhood cancer has become a curable disease, there are still cases where they face the harsh reality of the disease.

I still feel shaken when I see my child off,” she says. When I was in the U.S., I also volunteered at a hospice, and I read a poem there that said, ‘The brightness of life is not based on length. It said that each life, no matter how long or short, is very important and wonderful.

Then, Mr. Sasaki paused for a moment and said tearfully, “It is true that some children are actually children.

I have actually seen many children pass away, and I really feel that. Even though the length of life is different from the average, I think it was cool that this child’s father, mother, and other family members loved him so much and that he had so many friends see him off, and that he had so much fun. I truly believe that there are many people, including myself, who have been enriched and influenced by him.

It doesn’t make the sadness and loneliness go away, but I will cherish the time I was able to spend with her, and I will live my life from now on.

In 2011, Mr. Sasaki and other supporters involved in childhood cancer started the “Aichi Children’s Hospice Project” for children. Currently, there are only two community-based children’s hospices in Yokohama and Osaka that are not affiliated with hospitals and are independent of the medical and welfare systems, and they are working to establish a hospice in Nagoya.

We are working together with nurses, doctors, and mothers of former patients who we met while working at the hospital. The experience of hospices in the U.S. has always stayed with me, and I have always thought that such places are very important for children.

After all, there is only so much that can be done in a hospital, so I want children to grow up and become adults in the community. I would like to see a kind and warm society where children with illnesses and disabilities are supported in the community, rather than in a hospital. This is what we hope for in our activities.

In a hospital setting, medical care is inevitably the first priority, and sometimes the only goal is to defeat, overcome, or cure the disease. Children’s hospice is a place where children with illnesses or disabilities and their families can spend happy and childlike time in peace and quiet, based on the idea of valuing how they live and how they live, rather than on whether or not they can be cured. The hospice is together with the community, and volunteers and others are also working with a lot of zest and vigor. Aichi Children’s Hospice Project” has the philosophy of “Live life to the fullest, together,” and we would like to be there for the children as their lives shine brightly.

Interview and text: Miho Nakanishi

Nonfiction writer and representative of NPO Third Place. Formerly a reporter for a weekly magazine. After receiving twins through fertility treatment, she found out that her second son had a disability. Drawing on her own experiences, she focuses her reporting on assisted reproductive technologies, pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, disabilities, and welfare. Hon X (@thirdplace_npo)