Is it taboo to talk about politics at school? The Japan Chugakusei Shimbun asked Chikara Oyano, an education critic.

Questions erupt on SNS… “I talked about politics and my teacher got angry with me at school.

When the FRIDAY Digital article “‘Yumeshima Casino Can Be Stopped’…A Junior High School Student Launches ‘Japan Junior High School Student Newspaper’ All by Himself” (September 14) was published, a number of people commented, “There is an amazing junior high school student! The “Japan Chugakusei Shimbun” trended on social networking sites for a long time.

Another thing that stood out was the number of people who expressed surprise and concern about episodes in which their teachers were angry at them at school when they talked about politics.

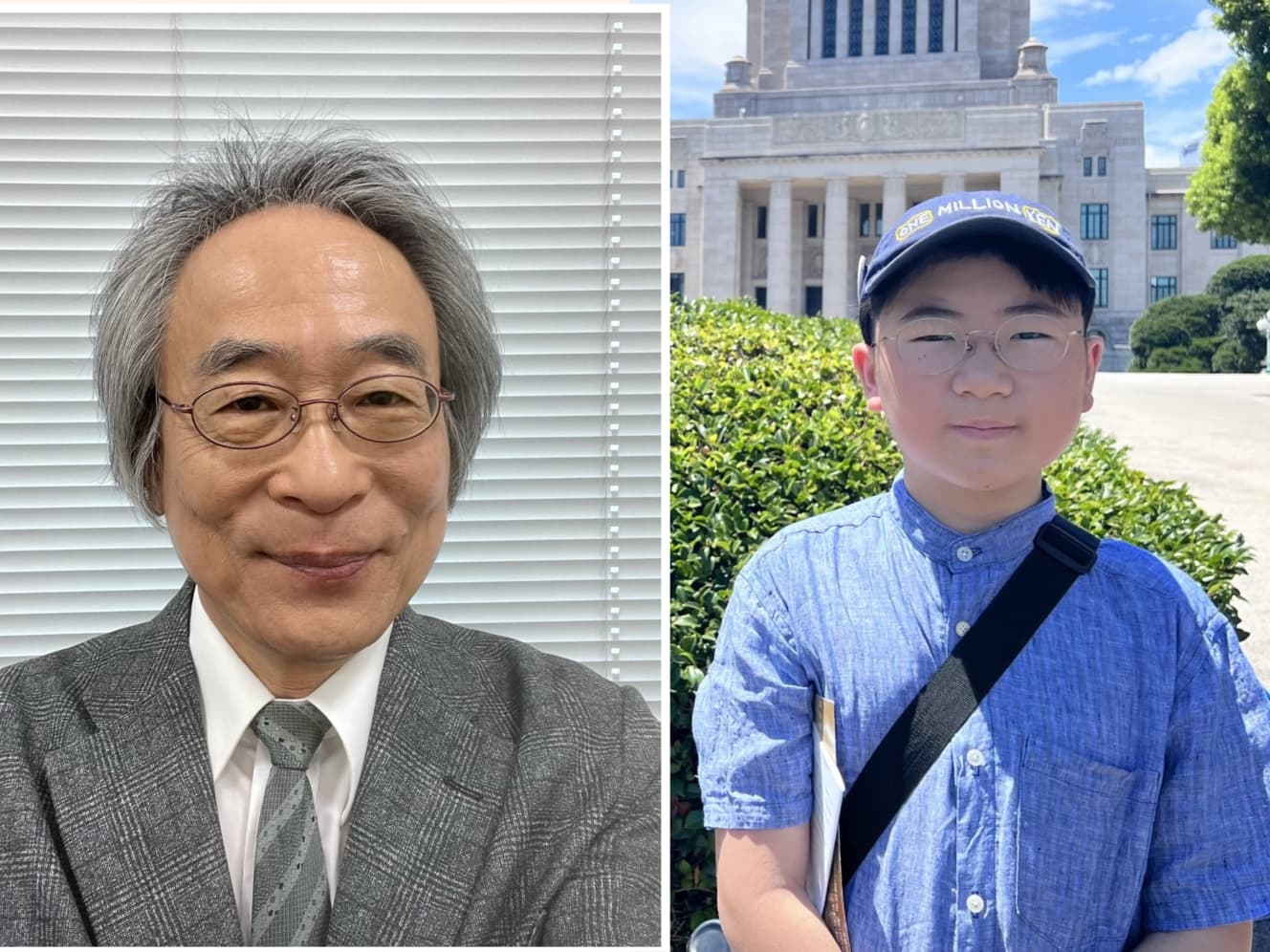

Therefore, we conducted a dialogue between Daiji Kawanaka of the Japan Chugakusei Shimbun and Chikayoshi Oyano, an education critic who has taught at public elementary schools for over 40 years, to discuss the relationship between the school scene and democracy in Japan.

When I was in the fourth grade, Osaka City held its second referendum on the Osaka Metropolis concept. When I talked about my concern that Osaka City would be abolished and citizen services would be cut, my teacher got angry with me.

Also, in the 5th grade, I was yelled at just for talking with a friend about how it would be easier to buy things if there were no consumption tax. In the 6th grade, when I wrote a statement for the newspaper committee about going out to vote, they would not post that newspaper.

Tomokazu Oyano (hereafter Oyano) I would have to say that was an overreaction. Of course, teachers have their own personalities, but I think there is an unspoken understanding in Japan that we have become too reticent to talk about politics at school.

This is because teachers have in their minds the wording of Article 14, Paragraph 2 of the Fundamental Law of Education, which states, “Schools prescribed by law shall not conduct political education or other political activities to support or oppose a particular political party.

In addition, there is also the “Act on Temporary Measures to Ensure Political Neutrality in Education in Compulsory Education Schools. These prohibit teachers from encouraging political groups and principles to children.

However, Mr. Kawanaka is not a teacher, but a pupil, and what he is doing has nothing to do with the law at all. Of course it should be allowed, and talking about going to the polls is not a matter of principle or anything else. I think there was probably an assumption in the teacher’s head that he should not deal with politics.

Kawanaka What do school teachers think about the “Convention on the Rights of the Child”?

Oyano: Even though they know that the Convention on the Rights of the Child exists and that Japan has ratified the Convention, few teachers have read the whole thing, and I think very few teachers understand its purpose.

One day, all of a sudden, without any reason given, udon and jelly were banned…

Kawanaka What I am interested in is what teachers think about democracy.

When I was in elementary school, there was a big incident that shook democracy. At my school, we had to eat lunch three times a week, but suddenly, without any reason given, udon and jelly were banned. It seemed that the vice principal made the decision with a single word of the crane, and the students were not allowed to express their opinions, so they just complied.

If the teachers want to decide on school rules, I can’t help but wonder why they don’t listen to the children’s voices. I think that if teachers listen to the voices of the children through surveys or polls, it will lead to a higher voter turnout for elections when the children eventually become adults.

Oyano: That is correct. In Japan, the right to vote has been raised to 18 years of age, and there is a lot of talk about “sovereign education. However, although it is a nice thing to say, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) seems to be assuming that high school students and above should be educated.

The report by the MEXT’s Council for the Promotion of Sovereignty Education, a panel of experts, on the implementation of sovereignty education in schools since the right to vote for 18-year-olds was realized in 2003, states that it is basically intended for education in high schools, and the supplementary materials used in classes are only intended for high school students. The report also states that the supplementary materials to be used in class are only for high school students. The report indicates that the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology does not envision elementary and junior high schools.

Kawanaka: I think sovereignty education is necessary in elementary and junior high schools as well.

Oyano: That is exactly right. In advanced Western countries, especially in Germany and other countries, they teach students from elementary school on how to solve problems in society, such as how to contact city hall, how to inform the media, how to demonstrate, and other specific methods. In Norway, in social studies classes at junior high schools, children sometimes go around to each political party and ask questions, and then summarize the differences between the parties and make a presentation.

Kawanaka: Actually, I also went to Tokyo during the summer vacation and visited the headquarters of political parties. I envy your education that you can go around to each political party and ask questions in school. I thought it was strange that we could not talk about politics at school, so when I was in the fifth grade, I read a book titled “Reading Swedish Elementary School Social Studies Textbooks: What Japanese University Students Felt” (Shinpyoron). At that time, I learned what Swedish education, political education, and sovereignty education were all about.

I believe that sovereignty education is something where each individual can learn to think and speak up, that there is more than one answer, to respect others, and above all, to be aware that democracy is something we create for ourselves.

Western children learn that they can “change their reality and their lives” if they take positive action on their own.

Oyano: It is necessary for children to learn about democracy in school. In France, children’s assemblies are held every year, and bills submitted by children are actually deliberated and sometimes become law.

In Japan, too, there are local assemblies for children, but they just read the prepared results and simulate them, and no law is ever actually passed based on a proposal submitted by a child.

Kawanaka It is very different from Japan that a law can be made from a proposal submitted by a child.

Oyano: In Japan, school rules are a matter of course, and even high school students are allowed to make decisions about hair and other matters by executive decision. On the other hand, in some countries, teachers, parents, and children discuss together to decide school rules, timetables, and subject content.

There is a big difference between Japan and other countries where children participate in school management and curriculum creation from elementary school onward. In Western countries, children learn firsthand from childhood that if they actively work on their own, appealing with arguments and taking action, they can change the reality and life in front of them.

I believe this is true sovereignty education and the basis of democracy. That is why the voter turnout in elections is so high.

Kawanaka In this respect, in Japan, people say, “No udon or jelly” without giving a reason, and they cannot complain or have their opinions heard.

Oyano In Japan, children are taught from childhood that they are powerless, and are imprinted, educated, and brainwashed to believe that anything they say or do is useless and will only make their unofficial report worse.

Kawanaka: Has there always been this kind of imprinting on children?

Oyano: There was a time in the past when student and labor union movements were active, but they ended without much success, and at the same time, the Japanese people as a whole shifted their goals to economic growth and pushed forward.

There is a kind of failure experience in the Japanese people. Besides, I think that the generation that has lived through a period of steady economic growth has been able to maintain a sense of value that it is good if you are happy, without having to say anything political.

More to the point, Japan has always been a rice farming civilization, and a kind of collectivist education has continued for a long time, with the value of cooperating with neighbors and everyone else.

In Japanese education, a teacher in a “good marching class” is regarded as having leadership and guidance skills.

Kawanaka It is true that many teachers and parents say, “Don’t bother others.

Oyano: When we surveyed parents about their child-rearing motto, “I want to raise my children to be people who don’t bother others” came in at number one or number two. Japan is the only such country in the world.

In Europe and the U.S., the most popular mottos are “I want them to show their individuality and do their best at what they love,” “I want them to make the most of their talents and be happy,” and “I want them to be useful to the world.

In other words, Japan is a country where “the stakes are high. The Japanese society as a whole, and Japanese school education as a whole, encourages people to “be average.

Kawanaka: There is a lot of pressure to be “average” and “fit in” with others. I have always wondered about the “marching” that takes place at athletic events. What are the teachers looking for and how do they feel about it?

Oyano: I experienced this when I was a teacher at a public school, and you can tell at a glance which classes are good marchers and which are not. The teacher of a class that marches well is regarded as having leadership and guidance skills. On the other hand, if the hands are not raised properly or the line is disorganized, the teacher thinks that his/her evaluation will be lowered.

Kawanaka Ah (smiles). I feel sorry for the teachers, too.

Oyano However, in Japan, the maximum number of students in a class is 40, so I think there is a kind of obsession that if everyone is doing different things, it is impossible to take care of them all.

Kawanaka At school, it is also a mystery why some teachers tell us not to drink during class.

Oyano Do they say that? Even though the dangers of heat stroke are now well known. Even 18 years ago, when I was a teacher, people were drinking during class at school. Did you hear the reason for the ban?

Kawanaka I had a friend who asked. The teacher said, “Because when one person drinks tea, those around him also drink, and I don’t want to create that kind of atmosphere.

Oyano: If you are thirsty and force yourself to work hard, you will not be able to concentrate in class, and it is better to drink water to keep your mind and body healthy. That is a problem.

Kawanaka When I encounter this kind of unreasonable situation at school, I wonder how to resolve it.

Oyano When you feel unreasonable, I encourage you to take notes. It doesn’t matter if you use your cell phone or write it down on paper, I think it is important to write it down and think about it or research it in your own way.

At the same time, what is also important is to listen to other people’s opinions, do research on the Internet, read books, etc. What is especially important is to have an open mind and an open ear to opinions that differ from your own, and to think from multiple perspectives.

If you forget your textbook… “It’s your own fault, so don’t ask your friend to show you the textbook.”

Kawanaka: Another thing that concerns me is the “self-responsibility theory. There are times when people forget their textbooks.

But they say, “It’s your own fault, so you shouldn’t ask your friends to show you the textbook. Without the textbook, you can’t participate in class, and you won’t understand anything if you only write on the board. You may even forget your gym clothes and not be allowed to take part in the PE class.

Oyano: That is not a viable form of education. Forgetting one’s belongings is a natural part of being human. However, to say that a student cannot participate in class because he or she has forgotten something is to interfere with the right to education, and is unacceptable.

In general society, when someone forgets something, it is natural to lend it to them. It is a normal human consideration. However, when a school teacher tells a child who has forgotten his/her textbook that he/she should not lend it to the child, he/she is saying that he/she should not help someone who is in trouble.

To begin with, there is the word “lost and found,” isn’t there? In English, there is no word that has the same meaning as the concept. Everything you need is at school, whereas in Japan, you have to bring your own compass, protractor, and everything else you need. It is inexcusable that they go to the trouble of making things difficult for you, when you can leave them at school and you won’t forget anything.

Kawanaka I am worried that Japan will become more and more like a dictatorship, falling behind the rest of the world, because money is not spent on education and children and grown adults are unable to express their opinions.

Oyano: Japanese common sense is like the world’s insanity, you know.

However, on Twitter (now X), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology tried to get people to write about the attractiveness of teachers as a “teacher baton” around last year. But all the tweets that came out were about how teachers are forced to work in black labor. I think it is a very good trend to see such honest opinions coming out.

I think that teachers should express their true feelings more and more and that a new trend may emerge in the future by making full use of social networking services. In fact, people like Mr. Kawanaka appeared one day out of the blue in the public eye, so it would not be surprising if such a presence appears in schools and among teachers as well.

Kawanaka Teachers can express their true feelings about how hard their labor is, and I think they will be happier if they work together to change the world.

Oyano: We live in a society in which the nail that sticks out gets hammered down, but I hope that Mr. Kawanaka will continue to stick out too much. A stake that sticks out halfway will be struck, but a stake that sticks out too far may not be struck by those around it. By doing so, there will surely be people who will be inspired by Mr. Kawanaka and follow in his footsteps.

Tomokazu Oyano is an education critic. Based on her experience as a teacher, she offers concrete suggestions on child rearing, parent-child relationships, and study methods. She is also a bestseller on Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), Threads, YouTube, and other social media. He is also very popular for his online and real-life lectures.

Daiji Kawanaka was born on December 11, 2010. Born and lives in Osaka City, first year junior high school student.’ In March of this year, he launched “Nihon Chugakusei Shinbun,” a “democratic reading material created by junior high school students,” having developed an interest in politics and railroads when he was in the third grade of elementary school. Currently, he is reporting on elections, the importance of sovereignty education in compulsory education, the Osaka-Kansai Expo, IR casino issues, etc. on X (formerly Twitter) and notebook.

Interview and text by: Wakako Tago

Born in 1973. After working for a publishing company and an advertising production company, became a freelance writer. In addition to interviewing actors and others for weekly and monthly magazines, she writes columns on drama for various media. His main publications include "All Important Things Are Taught by Morning Drama" (Ota Publishing), "KinKi Kids Owarinaki Michi" and "Hey! Say! JUMP 9 no Tobira ga Open Tokimono" (both published by Earls Publishing).