‘Why is it free?’ Younger generations don’t know what “delivery” means… Delivery now and then as seen in the buzz of tweets

The UberEats Generation vs. the “Delivery Generation” – Generation Z is not satisfied with the “delivery” system.

My daughter, a college student, is not satisfied with the “delivery” system at her neighborhood soba and udon restaurants. She says she doesn’t understand the point of having a heavy bowl of food delivered hot, not in a plastic container, and then having to make two round trips to pick up the food afterwards without paying a fee.

When such a tweet was posted on Twitter on May 8, it slowly gained likes and retweets, and within two or three days, it had more than 15,000 likes, creating a small buzz.

I am sorry to be so forward, but these are actually my own tweets.

I wondered what had suddenly happened to this frontier account, which is not very good at social networking. We wondered, and as we checked the replies and retweets, we found a surprising fact.

Generation Z does not understand “free shipping.

Looking at the accounts that “liked” or “retweeted” the post, it seems that the interest in this topic was widely spread across both the “UberEats Generation” and the “Delivery Generation”.

The most common response from those who appeared to be of the younger generation, including those with “college student” or “adult” in their account profiles, was, “What? Delivery was free?” I’ ve ordered delivery from my grandpa’s place, but I had no idea that delivery was free,” “I didn’t know that delivery was free…I sure don’t get it,” “It’s too good a deal, I don’t understand what it means,” and “Like my daughter, I don’t understand that delivery is “free.

The younger generation, who only knew about UberEats, which rapidly spread through the COVID-19 crisis, were surprised by the unknown system of “delivery,” and many were confused or impressed.

On the other hand, the middle-aged and older generation, who are familiar with the idea of “delivery,” expressed either freshness or shock at the reaction of the younger generation to the idea of “delivery.

- The younger generation doesn’t know about delivery service? The Showa era has gone far away.

- Those were the good old days.

- I haven’t had delivery for a while. I miss it.

- When I call the young people to ask for delivery, they often say, “It just came out,” but the food has not even been cooked yet. But often the food has not even been cooked yet.

- I suppose we no longer discuss whether or not to wash the dishes to be returned.

- I never noticed it before, but I guess delivery is something to be thankful for.”

The generation that can’t order delivery because of the wasteful fees

On the other hand, many of those who are familiar with delivery service said, “On the other hand, those of that generation would give up buying or eating by themselves if they had to pay for Uber and its high price setting and delivery fee,” “On the other hand, those who know about delivery service would not order Uber because of the wasteful fees and other charges,” and “Those who are of the generation where delivery service is common cannot get over the image of ‘UberEats is expensive. Many people said, “I can’t get over the image of ‘UberEats is expensive’ if I’m of the generation that used to have delivery service.

Also contributing to the excitement of the tweets were the various views on why the “no fee” policy was in place. All of the analyses have a point.

- Unlike disposable containers, rice bowls can be washed and used again.

- It was a business that was viable because there was no concept of cost in those days. Family-run businesses don’t incur labor costs.

- In the old days, there were many houses in the neighborhood that ordered delivery, so it was possible to make a profit on a thin profit margin.

- When there were a lot of orders for delivery, it probably wasn’t that much of a hassle since the containers could be picked up on the way to delivery.

- “In the case of delivery, the price should include the cost of delivery.

- Compared to delivery, eating in a restaurant requires more space for rent, time and labor to serve the customers.

- The delivery area is limited and the delivery is not made far from the restaurant. It’s a system that only works because it’s in the neighborhood.

- For the Showa generation, a system like Uber is more uncomfortable. The greatest merit of delivery service is that it ensures that customers order from our restaurant. It’s the best way to retain customers.

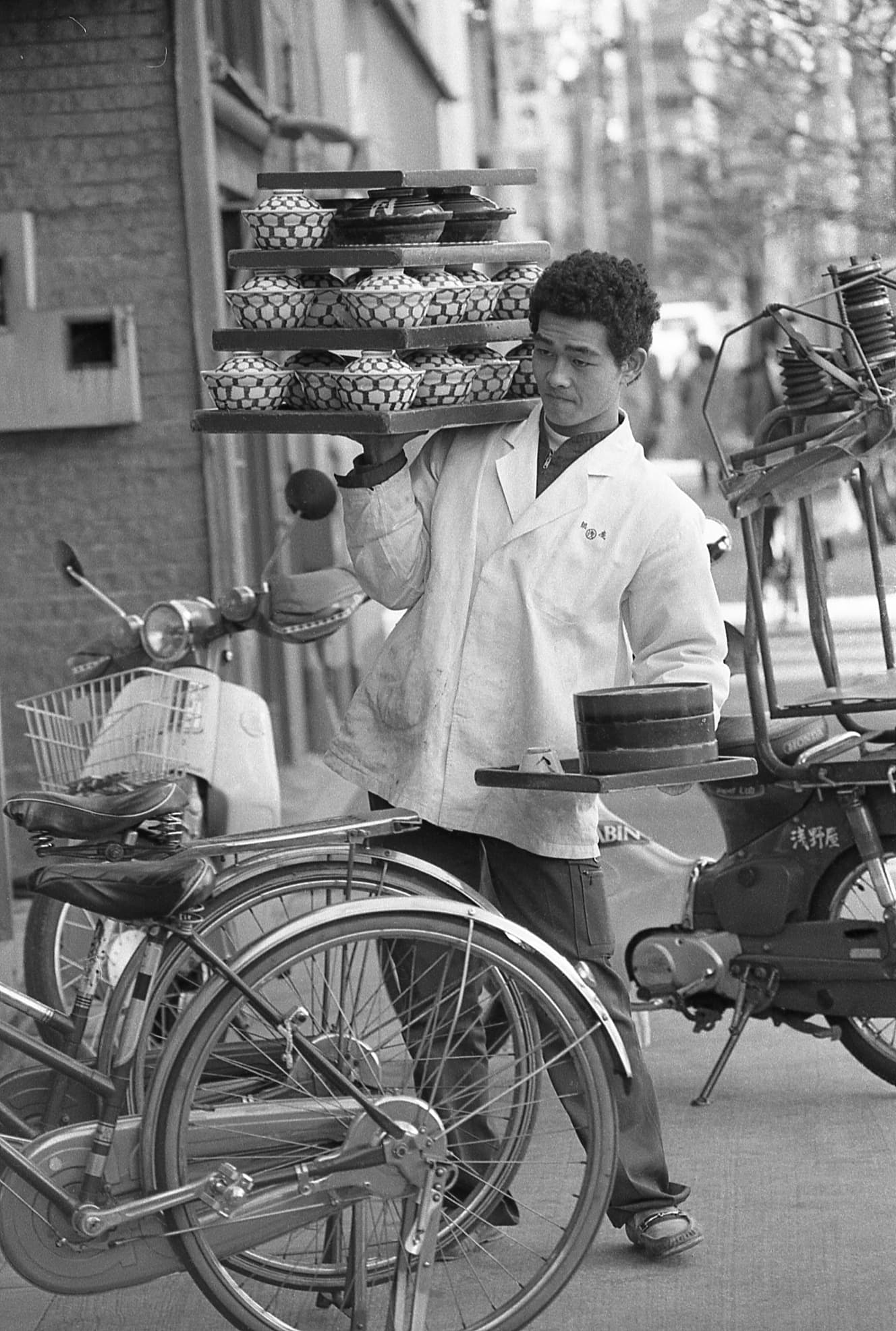

Cub”, “Okamochi”, “Tenoyamono”… The world of “delivery” is now filled with a sense of nostalgia.

The nostalgic power of the “delivery” content is also a major factor in drawing out the memories of each and every one of the customers.

- I used to think the machine attached to the back of the turnip to keep the juice from overflowing was amazing,” he said.

- There were restaurants that would even give you 10 yen back for the phone call.

- When I was a child, I used to long to eat okamochi.

- “I used to think it was cool when I saw a guy riding a bicycle on one hand while carrying okamochi on the other.

- There were ramen, machinuka, and sushi restaurants.

- I was so happy when I got my first delivery at my part-time job in college.

- I was happy when he brought me a bowl of rice wrapped in plastic so it wouldn’t spill.

- When I visited a customer, I was more entertained by delivery than by homemade food. It was bliss to be served.

- When I wanted to take it easy, I used to have the feeling of “shop-bought food”.

- When I was working overtime at the company, I used to have soba noodles delivered from a soba restaurant in front of the station.

- When I was in elementary school, my parents both worked, and during long vacations such as summer vacation, my childhood friend and I would often order udon for delivery.

- They also delivered shaved ice.

- He also delivered morning meals to a nearby coffee shop. They even delivered pudding à la mode.

- There was even delivery to my farm.

Many also see this as an unavoidable response to the changing times, with the declining birthrate, aging population, nuclear families, and single-person households, among other factors, leading to “solitary” eating.

- The problem with delivery is that you have to order a certain amount of food at once to get it to work, so you can’t order just one ramen. Uber is excellent in that you can order just one item, even though it costs more than the retail price.

- It’s sad, but it’s good because it saves the pickup person the trouble of having to pick up the bowl.”

The tweets about “delivery” were unexpectedly lively, with business elements that remind us of the changing times and nostalgic memories, as well as generation gap stories that resonate with both the UberEats generation and the delivery generation.

Delivery” at privately owned restaurants has been declining significantly.

Incidentally, according to an Internet survey on “delivery” conducted by My Voice.com, Inc. from October 1 to 5, 2010, “frequency of using meal delivery services” (comprehensive food delivery services such as UberEats and Izumekan, as well as delivery and

However, looking at the survey items related to ordering methods, “Websites/apps of each restaurant, etc.” increased significantly from 29.9% in ’18 to 39.2% in ’20 and 42.8% in ’22. The percentage of respondents who answered “Call the store” increased to 60.2% in 2006 and 60.2% in 2008, while the percentage of respondents who answered “Call the store” increased to 37.2% in 2010. The percentage of respondents who answered “call the store” decreased significantly from 60.2% in 2006, 47.0% in 2008, and 35.3% in 2010.

The restaurant industry was hit hard by the COVID-19 crisis, including voluntary restraint from going out, and among them, individual restaurants with little strength closed or went out of business one after another.

Amidst such a situation, the “delivery service” of private restaurants continues as a customer service that is an extension of neighborhood relations, even though it has been affected by UberEats, which expanded and spread rapidly after the COVID-19 crisis, and by the contracts with many restaurants, including major chain restaurants, and incorporated them into the system. However, the “delivery service” of privately owned restaurants continues to be a customer service that is an extension of neighborhood relations.

It is a system that is not worth the cost, but is very much appreciated from the user’s point of view.

Interview and text by: Wakako Tago

Born in 1973. After working for a publishing company and an advertising production company, became a freelance writer. In addition to interviewing actors for weekly and monthly magazines, she writes columns on dramas for various media. His main publications include "All Important Things Are Taught by Morning Drama" (Ota Publishing), "KinKi Kids Owanaki Michi" and "Hey! Say! JUMP 9 no Tobira ga Open Tokimono" (both published by Earl's Publishing).