A Miraculous True Story of a Prestigious Schoolgirl Who Attempted Suicide by Prostituting Herself for 10,000 Yen a Time… and Entered a European University at the Bottom of the Poverty Level!

Nonfiction writer Kota Ishii explores the reality of the "Young Homeless" who have lost their homes!

Mana Yamagishi (pseudonym) was temporarily placed in the care of the Child Guidance Center on three occasions due to abuse at home.

Why was she returned to her family instead of staying in an institution? Part 1: A Girl Suffering from Her Father’s Excessive Violence

Mana, who was first taken into temporary custody in her first year of junior high school, made the decision to leave the facility and return home on her own.

The violence at home was clearly excessive. But 12 However, for a 12-year-old girl, it was unacceptable to leave a prestigious school she had worked so hard to enter after only a few months and live in a prison-like facility without freedom.

Upon returning home, Mana began beating and hurting herself and attempting suicide. Her sense of self-denial from the abuse increased, and she became disgusted with life itself. She once came close to jumping off a building, and once attempted suicide by inhaling commercially available helium gas.

Looking for someone to buy me.”

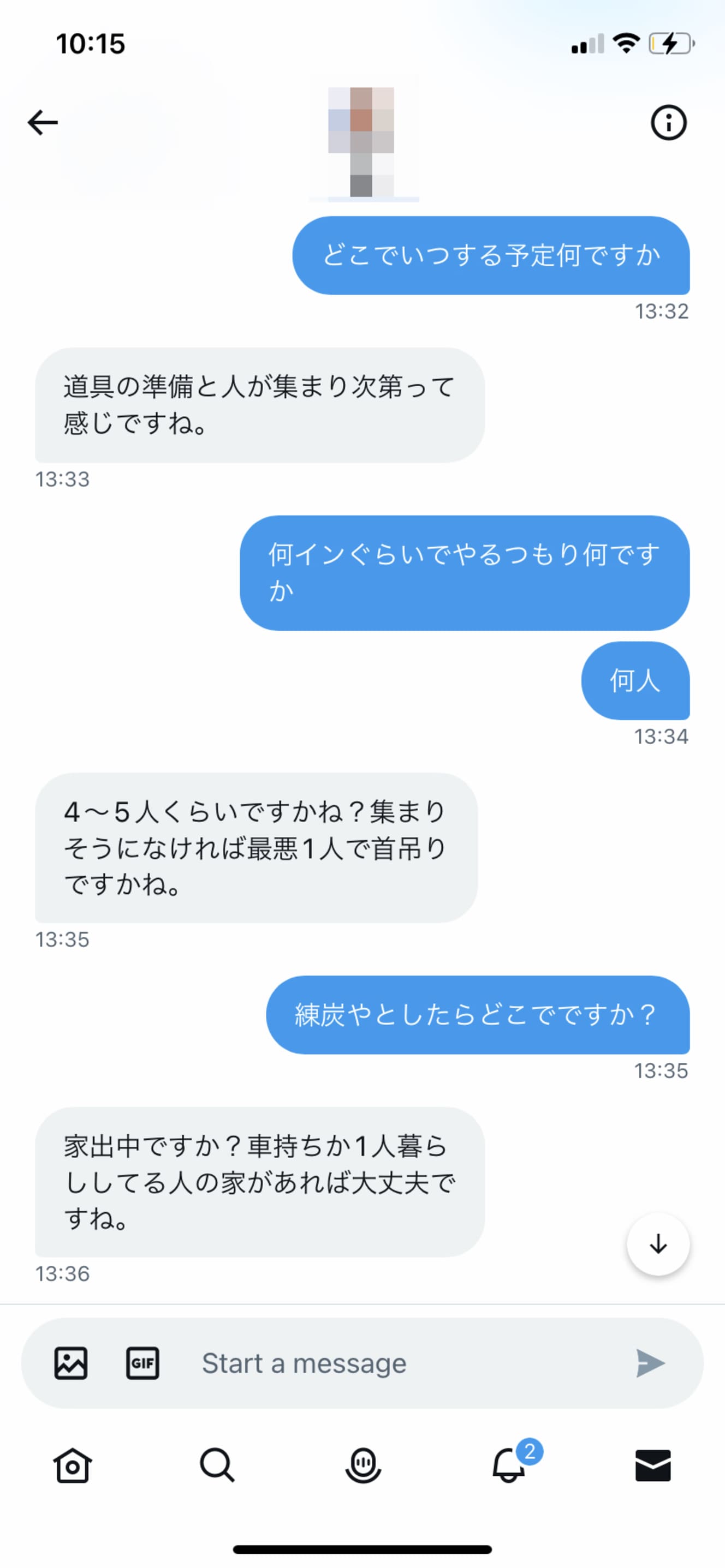

In the second year of junior high school, she began prostituting herself using her cell phone. On Twitter, she would post hashtags such as “I want to die” or “I don’t want to stay at home,” and men who saw these posts would send her direct messages at once. They would send her kind words and press her for a physical relationship. She prostituted herself to these men for 10,000 yen per session.

Mana says, “I didn’t want to stay at home.

I didn’t want to stay at home. But I was in junior high school, so there was nothing I could do. So I looked for someone who would buy me and let me stay at a hotel. Other times, I kind of got sick of a lot of things, so I did it during the day on weekends and after school.”

Abused girls may seek out the opposite sex in their hunger for affection, or hurt themselves in desperation. This manifests itself as sexual delinquency.

The second temporary custody by the Child Guidance Center came three years later, when she was a freshman in high school. Her father kicked her out of the house in the middle of the night, and she wandered the streets at night. The next day, with nowhere to go, she went to school in the same clothes she had been kicked out and told her father what had happened, and was once again taken into care by the Child Guidance Center.

After two weeks in a temporary shelter, she was sent to live in a self-support facility for less than four months. As with the first time, she was not allowed to go to school, but was only allowed to solve the handouts that were sent to her.

Mana says.

I was not allowed to leave the facility, so I was confined there for about four months. The hardest part was that I was forced to clean the facility for about three hours a day. Almost all of my mornings were spent cleaning. After that, I had to study using handouts from the school, but since it was independent study, I didn’t understand a word of it. It was hard for me to think why I was forced to do all the cleaning even though it wasn’t my fault, and why I couldn’t keep up with my studies.

For her, who was studying at a preparatory school, not being able to attend classes for four months and falling behind in her studies was unacceptable.

And here again, the caseworker told her the same thing that she had been told the first time she was placed in care. She had two choices: drop out of the private school and transfer to a different school instead of living in an institution, or return to her father’s house and continue attending her current school. The violence from his father was unbearable, but he could not accept the idea of quitting high school and living in a crippled institution.

I will go back home.”

She decided to go home again.

Her third temporary shelter visit was only six months later. This time, as well, she was evicted from her home in her nightclothes, to the absurd disobedience of her father.

Wandering around in her nightgown with a college student and ……

Mana wandered the streets at night in her nightgown and was invited to stay at the home of a college student who approached her. Of course, it was in exchange for sex.

The next day, Mana went to her high school in her nightgown. The high school teacher saw what was going on and contacted the Child Guidance Center.

At this time, she had been in the same self-support facility as before for about a week, but since she knew what the conclusion was, she decided to wait for her parents’ anger to subside before leaving. She no longer saw hope in the shelter itself.

She says.

My intention was to get out of the house right away and live somewhere safe. I was willing to put up with some inconvenience as long as I could escape my parents’ abuse. But I couldn’t accept quitting even school. That is a rule of the Child Guidance Center that will not change no matter what I say. Then, nothing would change even if they gave me protection. I think that’s how I felt.”

When Mana returned home from the facility, her family did not look at her at all. No one even said, “Welcome home. Are you okay? They just acted distant.

The same thing happened when I came home after a few days of prostitution. My parents and sisters must have known something was wrong, but they never mentioned it. I guess keeping their distance and feigning indifference to each other was the way they managed to keep the family together.

Mana’s turning point came after her third temporary custody. A young female teacher, who was in charge of her class, took a kindly interest in Mana. The teacher said, “I can’t intervene in the family’s problems.

I can’t intervene in the family’s affairs, but I will listen to whatever you have to say. But I will listen to whatever you have to say and do what I can do. So please feel free to talk to me anytime.

The teacher did not talk about the “now” but about the “future. Alone with Mana, he asked her what she wanted to do after entering university, what kind of future she wanted to open up, and what kind of society she wanted to live in. …… The teacher made Mana look forward to the future. He made her look forward to the future.

As Mana talked with him, she gradually began to focus not on the difficult situation at home, but on her own dreams. The dream she had at the time. It was to leave Japan, go to a foreign university, and work in international cooperation.

There are children like refugees in civil war zones who are in a much more difficult situation than I am, and I want to do something for them. I wanted to do something for them. I wanted to do something for them.

I can’t tolerate a society where ‘luck’ is the only answer.”

Fortunately or unfortunately, she had saved the money she had earned through prostitution and had set aside for her own independence and study abroad after graduating from high school. I want to leave home and become a person who can play an active role in the world. When Mana looked to such a future, her mind became at ease.

Now, three years later, Mana has left Japan and is enrolled in a university in a European country. Her major is international cooperation.

Why did Mana contact me and tell me about her experience? She tells me as follows: “There are many people who are abused.

There are many people who have been abused. Among them, I happened to find a good teacher and was able to escape from my family. But I think there are far more people who don’t. They have not been able to escape from their families for a long time, and they have become prostitutes and prostitutes. There must be many people who have not been able to escape from their families for a long time and are prostituting themselves or committing suicide. I couldn’t forgive society for dismissing such things as ‘luck. That’s why I wanted to share my experience.

What, in Mana’s eyes, is the problem with child welfare in Japan? When we asked her, she answered, “I say that child guidance centers are no good.

I don’t mean to say that child guidance centers are bad. They are doing their best within their own rules. But I think there is a problem with those rules.

Under the current rules, the abused child, not the abusive parent, must be sent to an institution and have his or her freedom taken away. Or a child attending a private school must drop out and move to a public school. Isn’t that crazy? There is more to it than this.

If these rules had been different at the time of my first protection in the first grade, I would have been able to escape my father’s abuse. How is it that something like that can change my fate?”

It is true that if Mana had gone to an institution at the first temporary shelter, she might not have repeatedly attempted suicide or engaged in prostitution.

Like Mana, I do not intend to criticize the Child Guidance Center. I have been personally involved in various ways because of my work, and I am truly bowled over by the dedication of the people at the Child Guidance Center to their work.

However, as she points out, if there are problems on the part of the system, they will have to be fixed. At least in Mana’s example, the system is not necessarily designed from the child’s perspective.

Is the temporary protection system really designed for the child? We need to reconsider this question.

The children’s welfare system is not necessarily designed for the benefit of the children. It is possible for a child to attend a private school from a foster home, but there are various conditions, and in Mana’s case, they did not apply.

Wanted.

The series “Young Homeless” is looking for people in their 10s to 40s who have no permanent place to live. We are looking for real-life experiences of people who have lost their housing, either now or in the past, such as people living in cars, Internet cafe refugees, migrant sex workers, day laborers living in dormitories, hotel dwellers, store dwellers, and people living in support facilities, as well as the voices of those who are providing support for these people. Anonymous or other conditions are acceptable, so please contact the author.

Kota Ishii (Author)

Twitter @kotaism

Email postmaster@kotaism.com

Interview, text, and photography: Kota Ishii

Born in Tokyo in 1977. Nonfiction writer. He has reported and written about culture, history, and medicine in Japan and abroad. His books include "Absolute Poverty," "The Body," "The House of 'Demons'," "43 Killing Intent," "Let's Talk about Real Poverty," "Social Map of Disparity and Division," and "Reporto: Who Kills the Japanese Language?

Photo: Courtesy of the filmmaker