Frequent North Korean missile launches…can evacuation to underground stations save lives?

Depending on the power of the missile and the point of impact, there is a risk of being buried alive!

North Korea has been repeatedly launching missiles at an unprecedented pace.

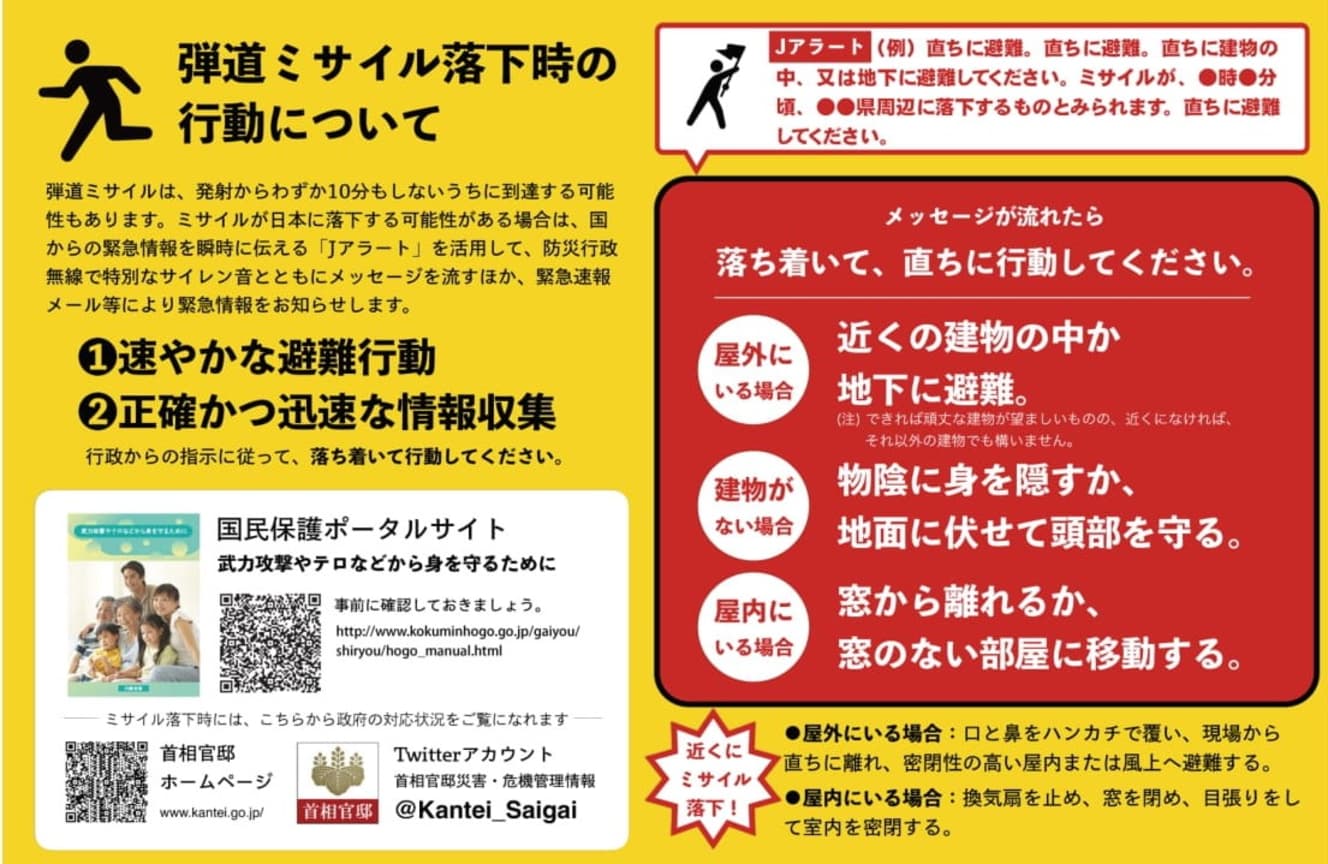

On October 4 last year, a missile passed over Aomori Prefecture and fell into the Pacific Ocean about 3,200 km east of Iwate Prefecture. J-Alert alerts sounded in Hokkaido and Aomori prefectures and, due to a false alarm, on the islands of Tokyo, and emergency alert e-mails were sent to smartphones and other devices urging people to evacuate to buildings or underground.

On social networking sites, people asked, “What is underground in Aomori?” A series of posts by Aomori residents such as “Even if you are told to evacuate when there is no underground ……,” were apparently posted by a number of local governments that have designated underground stations as “emergency temporary evacuation facilities” due in part to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to the Cabinet Secretariat, as of October 1, the number had increased to 516 stations nationwide.

But are underground stations really effective against missile attacks?

“Depending on the combination of the severity of the missile attack and the underground station from which you flee, there may be cases where you can be saved, but there may also be cases where it is more dangerous,” said Ohmae Osamu, a lawyer.

The answer is “yes,” according to Osamu Omae, a lawyer. Mr. Omae, who was a member of the defense team for the “Osaka Air Raid Lawsuit,” in which victims of air raids at the end of World War II sought compensation from the government, is familiar with the Air Defense Law, which prohibits subway facilities from being used as evacuation sites in the event of an air raid.

The National Protection Law requires prefectures and government-designated cities to designate evacuation facilities in case of armed attack, and this year the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, cities in the Kansai region, Sapporo, Yokohama, and Fukuoka have designated subway stations. In May and September, Tokyo, the capital of Japan, designated 129 stations, including those of the Toei Subway, Tokyo Metro, and private railways, as emergency temporary evacuation facilities.

Incidentally, the government is “promoting the designation of underground facilities (underground station buildings, underground malls, underground passageways, etc.) as priority areas.

Some stations on Tokyo’s Ginza Line and Marunouchi Line are not very deep. If the underground station is shallow from the ground level, you will have to evacuate just below the road, and depending on the power of the missile and the point of impact, there is a risk of the road collapsing and burying you alive.

The narrowness of the stairwells may also be a problem, and if a J-Alert sounds and everyone tries to run for cover, a panic may ensue. Even crushing deaths could occur.

It would be better if the government had calculated the impact and blast resistance of the missiles and the population living and working in the area, and then designated them as evacuation sites because they are appropriate. I don’t think it can be said that evacuation to the designated underground stations is an effective measure.

Underground stations are only temporary evacuation sites for one or two hours, so naturally they are not equipped with stockpiles.

There is no stockpile of food and no power supply. It does not function in any way as an evacuation site. Despite this, the government is pushing for the designation of underground stations. It is highly doubtful that the government seriously intends to protect the lives of its citizens.

During the war, Japan was told, “Don’t flee to subway stations during air raids, put out the fire.”

It is often reported that Ukrainian citizens took refuge in subway stations after the invasion by Russia.

In his “Wartime ‘Air Defense Law’ Information Site,” Ohmae mentions the evacuation of London’s subway stations during wartime.

He says, “Since the time of World War I, London’s subway stations were used as evacuation sites. However, there is no record that subway stations were constructed in advance to withstand air raids.

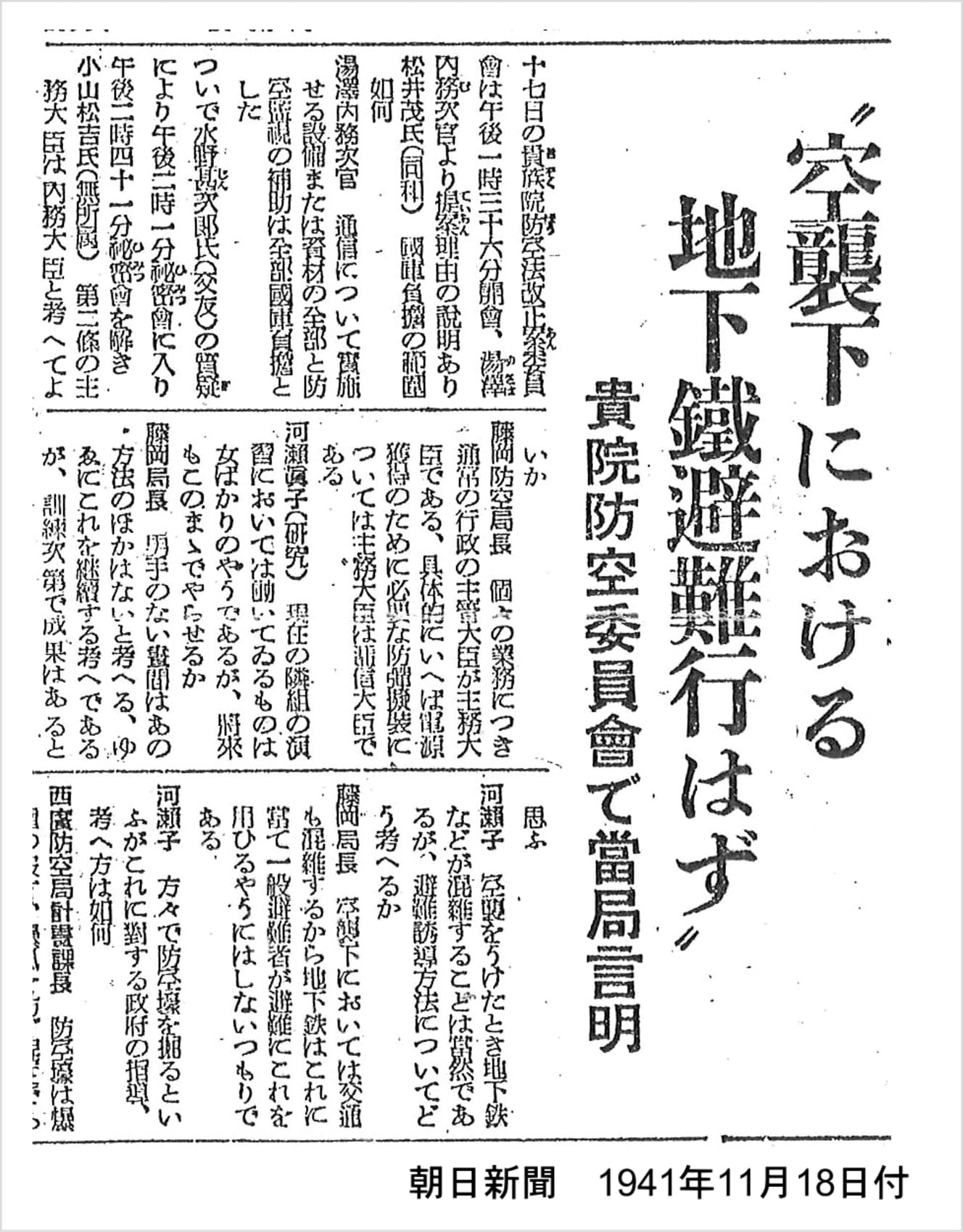

In 1941, one month before the outbreak of war between Japan and the U.S., the Japanese government announced in the Imperial Diet that it would not allow subway stations and facilities to be used as evacuation centers in the event of air raids.

The reasons for this policy were that “after an air raid, people would have to take their own lives to extinguish fires, so escaping to underground stations would not be allowed,” and “during an air raid, transportation for military and firefighting purposes would take priority, so it would be impossible to allow them to be used for evacuation of the general public.

The wartime “Osaka Prefectural Air Defense Plan” (enacted in 1943) stipulated that subways should run every 10 minutes when air raids began in the middle of the night. However, this was for the purpose of using the subways to transport rescue personnel and supplies, and citizens were not allowed to enter the stations. They were told not to flee to the underground stations and to put out the fires.

The incendiary bombs used in the 1945 raids by U.S. aircraft were mainly aimed at burning wooden houses. Relatively few of the bombs were powerful enough to make large holes in the ground, so it made sense to flee to the underground station. But at the time, the policy was, ‘Do not flee to underground stations.

Now, North Korea flies missiles, not incendiary bombs. In some cases, underground stations may be destroyed, but they are telling people to evacuate easily. The measures taken during the war are exactly the opposite of those taken during the war, but the fact that the government is not seriously trying to protect the safety of the people has not changed in 80 years.

What is transparent from the government’s actions to stir up a sense of crisis is ……

Mr. Ohmae further points out that “the government’s attempts to stir up a sense of crisis among the public is problematic.

J-Alerts are meaningful if they are operated under a comprehensive evacuation plan that protects people’s lives and livelihoods. However, the evacuation plan itself does not do so. In short, the government probably does not really believe that there will be a missile crisis or damage that will take the lives of the people.

Therefore, I think the purpose of the government’s J-Alert is to stir up a sense of crisis, not to protect the people. The purpose is to induce people to believe that Japan is in danger, that it must double its military spending, and that it must change the Constitution to position the Self-Defense Forces as a military force. I think that kind of agenda is transparent.

The first J-Alert was issued a minute or two before the North Korean ballistic missile passed over Japan. It is perhaps not surprising that the Japanese government’s awareness of the need to protect its citizens is as weak as it was at the end of the war 80 years ago.

Osamu Omae is a lawyer. Graduated from the Faculty of Law, Osaka University. After working for a railroad company, he registered as a lawyer in 2002 (Osaka Bar Association), and since 2015 has served as Deputy Secretary General of the Japan Federation of Bar Associations’ Center for Legislative Measures. In the Osaka air raid lawsuit, he clarified the national policy during the war. He is co-author of “What Did the Osaka Air Raid Lawsuit Leave Behind?” (Seseragi Shuppan) and author of “Don’t Run Away, Put Out the Fire–Senso Shita Tondemo Boei Houhou” (Godo Shuppan).

Interview and text by: Sayuri Saito