Amidst a power harassment racket…Allegations of “defeat order” by the former national team and Juntendo University coach.

Takumi Horiike, the coach of Juntendo University, a powerhouse university soccer team that has been the subject of power harassment allegations, has come under new scrutiny after it was revealed that he ordered his players to “lose” at the Amino-Vital Cup in June 2016, a qualifier for the Prime Minister’s Cup tournament, in order to get into a more competitive group for the August 2016 tournament, according to several players who were with the team at the time. The J-League has been known to intentionally “defeat” teams in order to make it easier for them to play in the tournament.

In the J-League, if a player is found to have intentionally “ordered” a team to lose, he or she is held responsible for “raising doubts about the maintenance of trust and integrity in sports, not just soccer,” and faces severe penalties, including revocation of club licenses. If true, this will likely lead to a question of whether or not Director Horiike will be allowed to continue his career.

Director Horiike is a former Japanese national soccer team player from Shizuoka Prefecture. When he was a student at Shimizu Higashi High School, he was known as one of the “Three Crows” along with Kenta Hasegawa (current J1 Nagoya manager) and Katsumi Oenoki (Shimizu S-Pulse GM), and after graduating from Junko University, he played for Shimizu S-Pulse and other teams. He was a member of the “Doha Team” that won the 1994 World Cup in the United States with Hajime Moriyasu, Japan’s national team coach for the World Cup in Qatar in November, and other players such as Tomoyoshi Miura and Rui Ramos.

After his retirement, he worked as a commentator on “Yabecchi F.C.: Japan Soccer Cheering Manifesto” and was one of the “J-League Legends” who worked hard to popularize soccer with a fresh smile. A report in the “Weekly Bunshun” revealed allegations of power harassment, including verbal abuse of players within Juntendo University’s kickball club, but we came across an even more shocking piece of information about coach Horiike.

It was the summer of 2016. It happened in the locker room where the players were gathered for a match against Nichita University in the Amino-Vital Cup, a qualifier for the Prime Minister’s Cup, the competition to become the best university in Japan.

Don’t win this game! Don’t win this game! Okay?”

The person who made the comment was none other than coach Horiike. If this statement was true, it violated the intentional “order to lose” rule. One player who was a member of Jundai at the time nodded his head deeply as he recalled the incident.

He said, “The statement is exactly right. It is true that such instructions were given to us so that we would have the upper hand in the tournament. Many members of the soccer team, including myself, felt that ‘such things should not happen in the educational arena of college soccer.

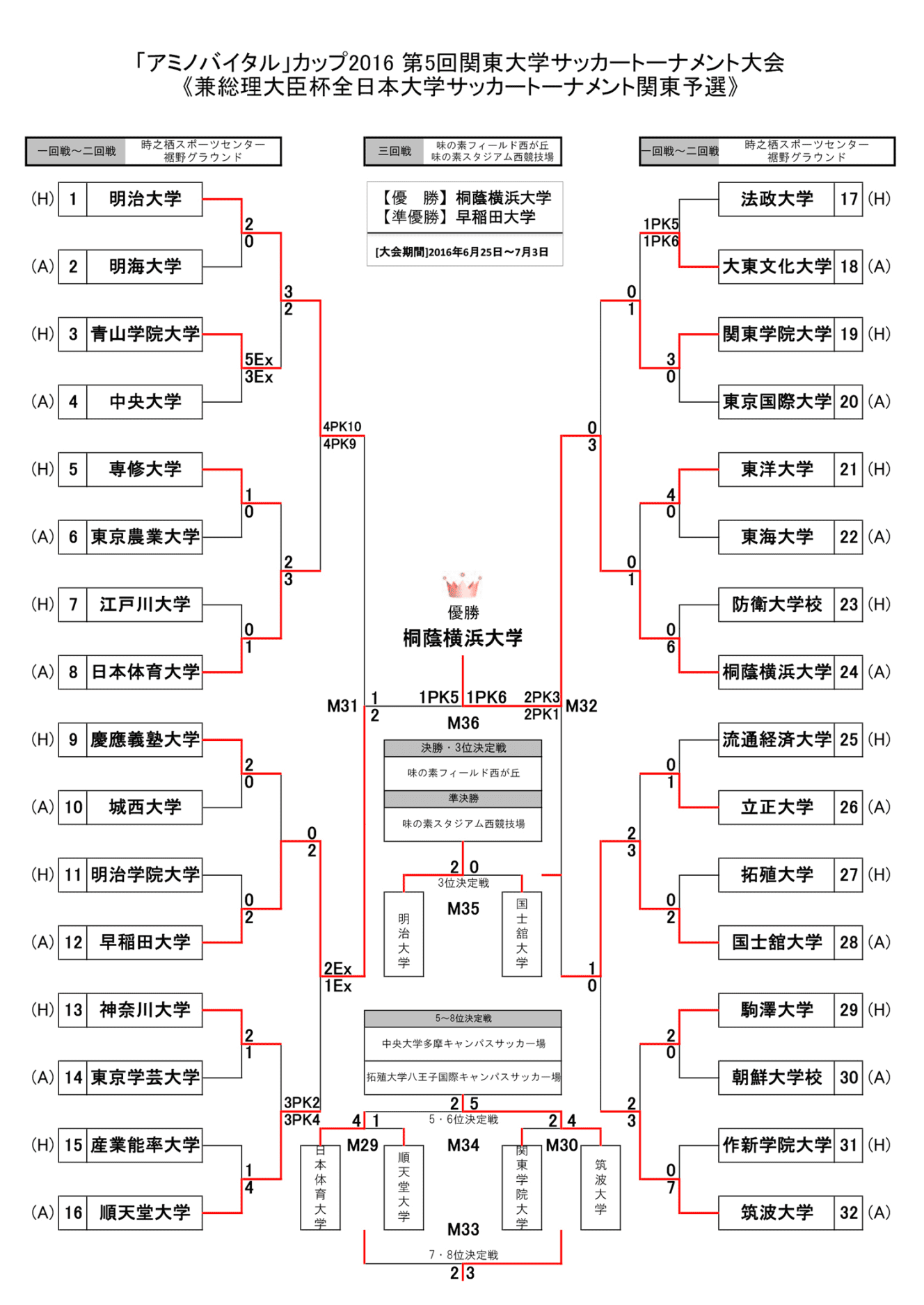

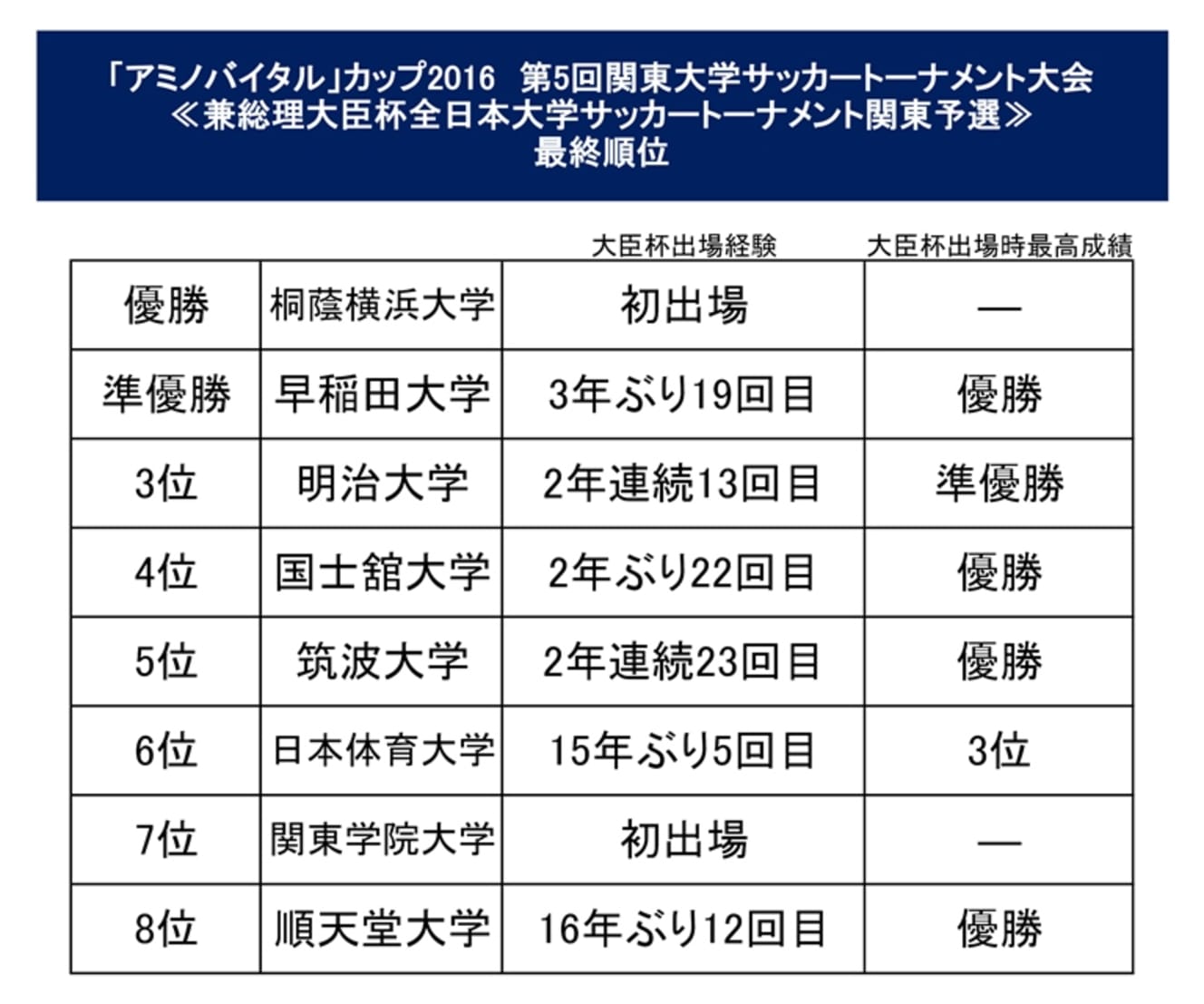

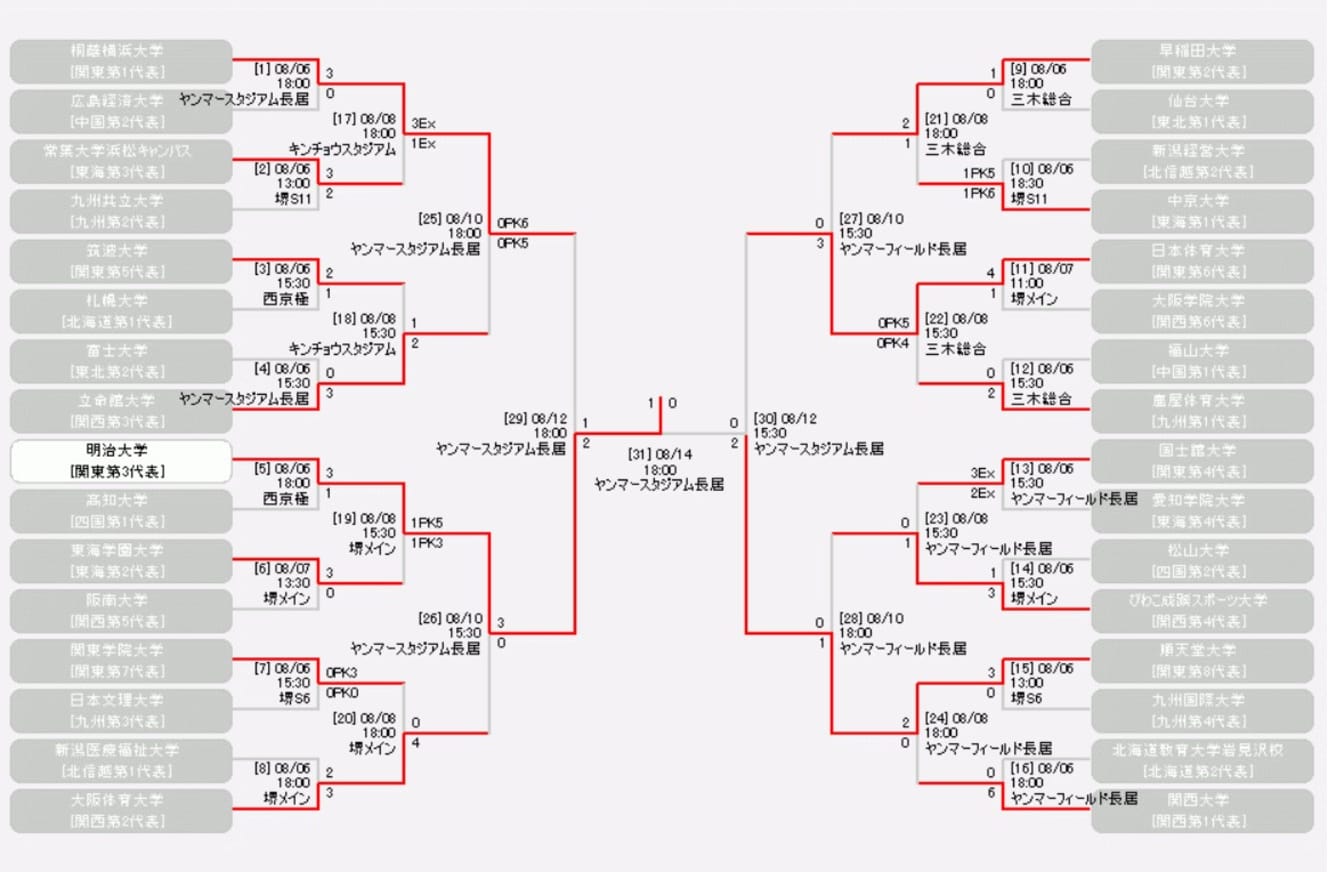

In 2016, 32 schools from across Japan gathered to compete for the Prime Minister’s Cup in a tournament format, and the Amino-Vital Cup held from June to July was positioned as the Kanto preliminary round of the Prime Minister’s Cup, with the top eight teams qualifying for the Cup. At the time, Toin University of Yokohama, Meiji University, and Waseda University were strong, and the fifth, sixth, and seventh representatives were likely to face those three schools at an early stage. If the team lost the match against Nisshutai University and placed 8th, it was a combination that would not play those three schools until the semifinals. It is expected that this was also a “strategy” to advance to the top of the Prime Minister’s Cup Tournament.

Although the JUNDAI Kickball Club was runner-up in the Prime Minister’s Cup, the students who were told to “lose” were left with an unsettled feeling in their hearts. A former member of the team continued.

One day after the tournament, we asked the university to boycott the training of coach Horiike. However, I could clearly sense the university’s attitude of ‘We don’t want to make a big deal out of it. I will change,” he promised the players and the university. …… In the end, it took him less than 10 days to break that vow. It took less than 10 days for them to break their pledge, and their offer to boycott the tournament was squashed by the university.

For university student players aiming to become professional soccer players, the university league and cup competitions, where they compete for supremacy to become the strongest of the year, are valuable stages. Especially for the upperclassmen and promising players, it is an important place to appeal themselves to the scouts of J clubs and their agents who guide them to J clubs. Junya Ito, who played in the final Asian qualifier for the World Cup, is an alumnus of Kanagawa University, and Reo Hatate, a strong candidate for the World Cup team, is an alumnus of Junko University.

However, as in any other field of soccer, if a player does not play in games, his chances of reaching his dream do not increase. While there are players at universities who can make it from their first year as professionals, there are also players who may or may not make it.

It is difficult to evaluate whether or not equality is maintained in the selection of players, since it depends on the circumstances of each university team, but in the case of Jundai, the players had a sense of crisis: “If Mr. Horiike does not like us, we will not be used in games” (Jundai alumnus). Furthermore, the players were routinely verbally abusive, and it was difficult for them to express their opinions directly to coach Horiike. The players, who dreamed of becoming professionals, had no choice but to accept the unreasonableness of “orders to lose” and “power harassment.

If you play with the assumption that you will lose, it is difficult to perform at your best, and it is difficult to say that your dream of becoming a professional player will come closer. One J-League player who is an alumnus of Juntendo University said, “In my case, I had to go through Juntendo University.

In my case, I had a dream and motivation to return to a J. League club with a youth team that had nurtured me through Juntendo University, but that dream was cut short during my college years. I think one of the reasons why I was not able to fully demonstrate my abilities was due in large part to the “atmosphere” that was prevalent in the club. I hope that this incident will come to light, and that there will be even a small chance that younger students in the same situation as myself will not have to go through the same experience.

The power harassment that forced him to accept the order to withdraw from the competition began about six months before he entered JUNDAI. One JUNDAI alumnus revealed, “At that time, Mr. Horiike said, ‘I’m not going to accept the orders to leave.

At that time, Mr. Horiike had a lot of media exposure, including on “Yabecchi,” and even high school students themselves knew him as a former national team player. After the summer of our junior year in high school, when we were agonizing over our career path, he would visit us at games and training sessions and talk to us with that “Horiike-san” smile from the TV show. First of all, he said, “You know, we will use you in our games from your first year. At the time, we wanted to become professionals, and a coach like that was a lifesaver for us, so I and my family gladly chose to go to JUNDAI.

However, after attending a few practices and exchanging information, he noticed something unusual.

For some reason, the players who used to belong to JUNDAI told me, ‘You shouldn’t come here. You definitely shouldn’t come here.’ ‘If you’re talking about another university, choose that one.'”

As soon as they enrolled, they understood why. What they saw was not the “Mr. Horiike” but the way he repeatedly frightened the players on a daily basis.

One of the players who was singled out for criticism in the match was abused on the bench at the end of the first half and ordered to be replaced. The player was relegated to the sub team, but there was no specific training or advice from coach Horiike on how he could play for the top team again to improve. After another game, the players were repeatedly subjected to intensive verbal abuse, saying, “We lost because of you,” and “The players on the team you grew up with are all dim-witted. In many cases, players who entered the school with a recommendation quit because they could not stand such a routine.

One soccer journalist analyzed the situation as follows.

One soccer journalist analyzed the situation as follows: “I think coach Horiike wanted to take credit for the results of training the players he was involved in scouting and liked. When Horiike took over at Jundai in 2014, the players were recruited according to the policy of the previous coach, so it would be easier for him to color the players according to his own color if he gave them many opportunities to play with lower-ranked players.

The ones who will take the brunt of this will be the older players who have a proven track record. By having them sit on the bench instead of playing in games, the atmosphere of “If you don’t do what I say, you will be removed from the team” must have been fostered. The university side, which is in a position to objectively monitor the situation, seems to have too much respect for Director Horiike and former Jundai alumnus Hiroshi Namba (current J3 Matsumoto coach), who is also a former member of the Japan national team, to say anything.

Another J-League player, who spent four years under Horiike, looked a little further afield as he spoke of his feelings deep in his heart.

We have seen our friends leave the club and have carried their thoughts and feelings with us all the way to this point,” he said. But the reprimands and abuse I received back then, beyond the guidance I received, are still with me today. I hate that.”

The former standout player, who attracted attention from the pros in high school but left soccer after graduating from college, reveals in a trembling voice, “Above all, I am grateful to my teammates and the good things they did for me.

When I look back on the memories of my time on the Juntendo University kickball team, they are so painful that I have been thinking, ‘Let’s erase the memories of my college days, let’s forget about them. I have been trying to ‘erase or forget the memories of my university days. Otherwise, it was all unbearable. I have the memories, but there is still a sadness that outweighs them.”

If what FRIDAY Digital reported is true, then Jundai knew about coach Horiike’s “order to take defeatist action,” but left the issue unresolved and allowed him to lead the team until recently. This is as sinful as the actions of Director Horiike. We contacted Jundai to confirm the facts, but they simply repeated, “We have nothing to say to you at this time. They did not even accept the questionnaire I had prepared for them.

How could JUNDAI have developed such an irrational and unreasonable attitude of accepting “orders to act in defeat” without telling anyone? Unless JUNDAI confronts coach Horiike and the players head-on and demands improvements, there will continue to be victims who will feel the “darkness” of their glorious youth.